Readings for the First Sunday after Christmas Day

This sermon was preached at Christ Episcopal Church in Eureka CA on December 28, 2025.

The Eagle Lands: Genuflection as Embodied Expression of Incarnation and Deification

The Eagle Lands: Genuflection as Embodied Expression of Incarnation and Deification

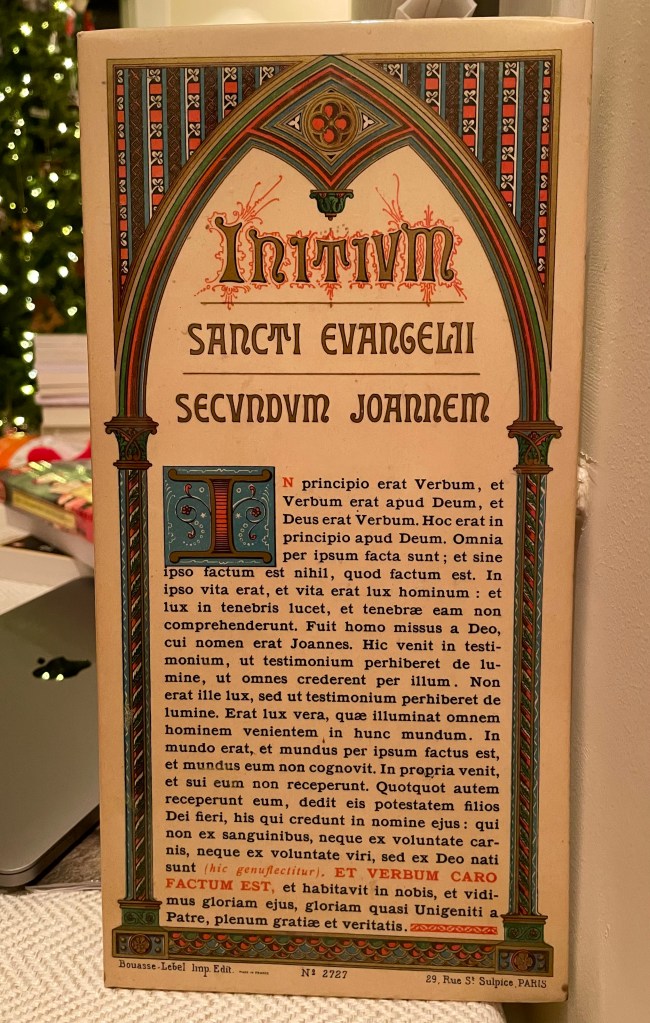

There’s an old liturgical practice that began at Salisbury cathedral in medieval England called the “Last Gospel.” The practice began as a private devotion of the priest who would read, on his own, at the end of Mass, the Prologue of John’s Gospel (which we just heard). Over time, this private devotional practice was absorbed into the official rubrics of the Mass so the priest would read aloud John’s Prologue after giving the final blessing. In medieval England, this was the only part of the Latin Mass that was read in the vernacular, in English. And when the priest arrived at that phrase, “The Word became flesh,” he and the entire congregation would genuflect. This remained a common practice in Roman Catholic churches until Vatican II, when it was omitted, some say because there were too many superstitious beliefs associated with the reading of these words. Some believed that simply reading and hearing these words had the power to drive out demons and evil spirits as well as sickness and disease. These days, we hear this reading of John’s Prologue maybe once or twice a year around Christmas time, but for hundreds of years, this was read at the end of every single Mass so that most people had it memorized, especially that most important phrase of all: And the Word became flesh. Et Verbum caro factum est.

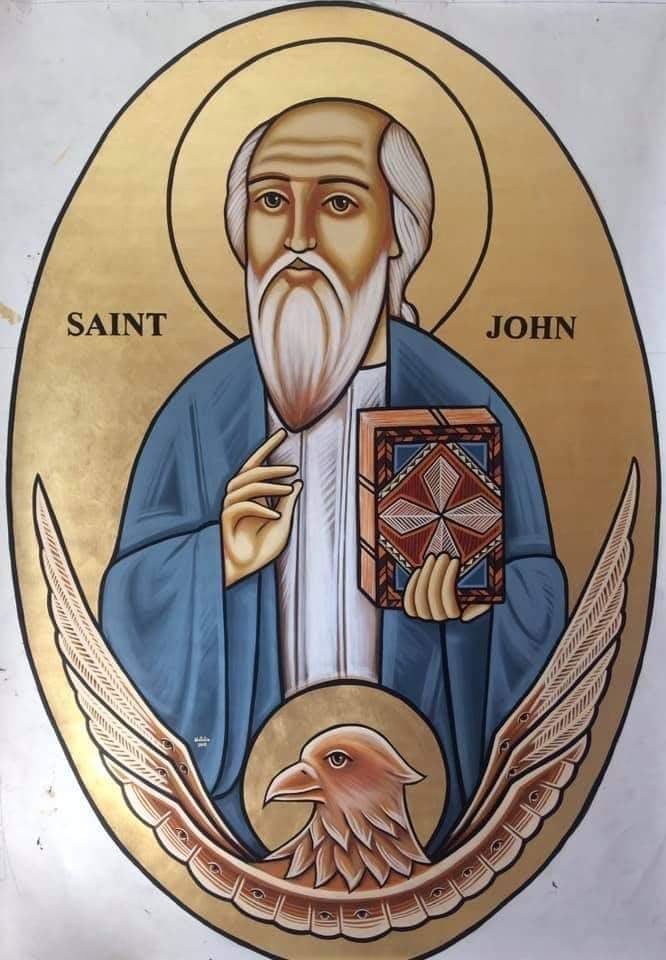

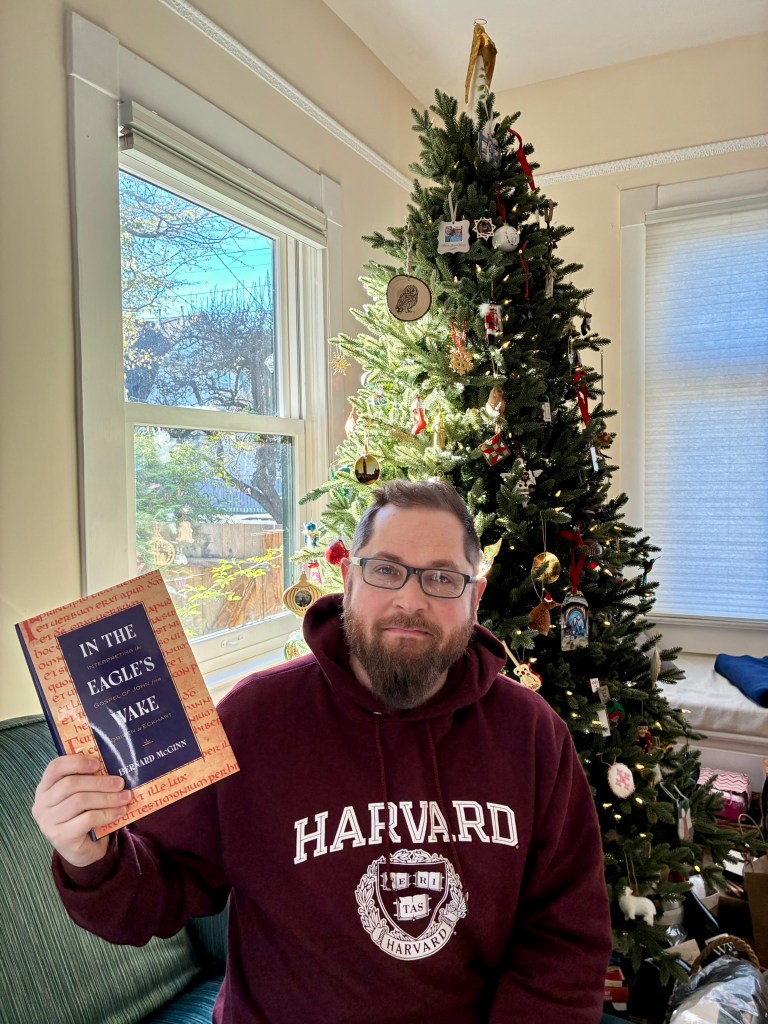

I love that this “Last Gospel” practice seemed to have originated in England because the Gospel of John has remained the most favored and beloved Gospel among the English and Anglicans for whom the mystery of the Incarnation remains central. For Christmas this year, I received a book titled In the Eagle’s Wake: Interpreting the Gospel of John from Origen to Eckhart by Bernard McGinn; and in it, he summarizes the sermons and commentaries on the Gospel of John by medieval saints and scholars, including the pope responsible for founding the Ecclesia Anglicana in 597: St. Gregory the Great; the Father of English Spirituality known as the Venerable Bede; and the Celtic mystical theologian John Scotus Eriugena. Each of them engaged deeply and creatively with the prologue to John and they all seemed to agree that the traditional author of the Gospel, John the Evangelist, begins his Gospel by soaring like an eagle among the highest heavens in his prologue, proclaiming “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.” And this is why our Christian tradition has associated St. John the Evangelist with the symbol of the eagle (which is why McGinn’s book is titled In the Eagle’s Wake and which is why we have an eagle lectern). The English medieval scholars (Gregory, Bede, and Eriugena) also seem to agree that the eagle lands as the Evangelist proclaims that “the Word became flesh,” that phrase which Archbishop of Canterbury William Temple called the most important phrase in all of Christianity, that phrase that compelled the faithful for centuries to bow and genuflect.[1]

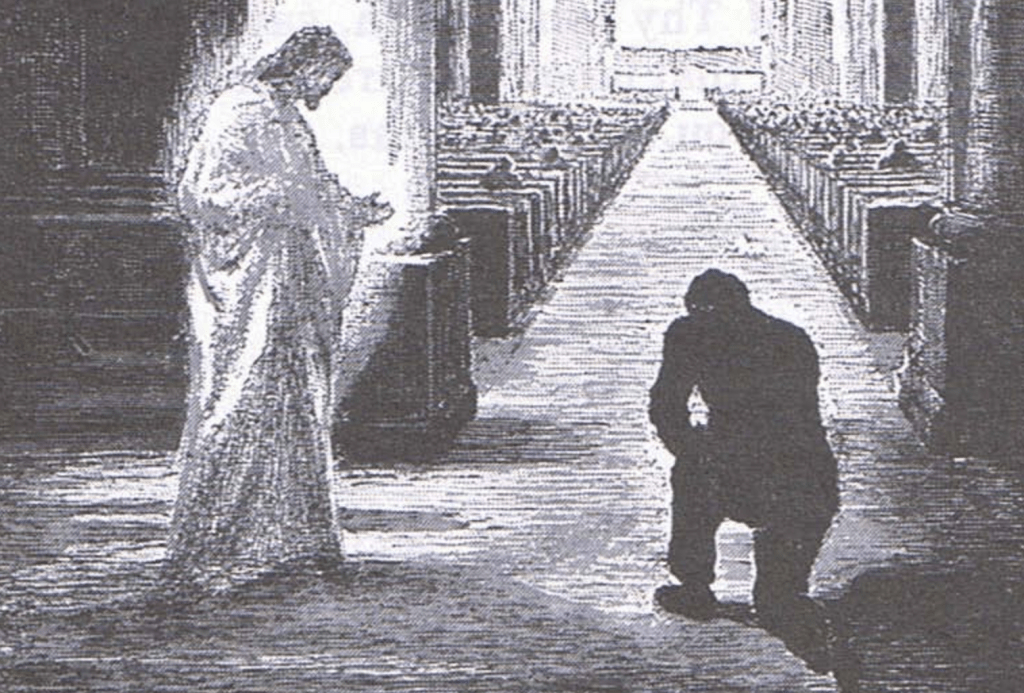

Now we bow and genuflect often throughout the liturgy of the Holy Eucharist. Our custom here is to bow a simple bow whenever the name of our Lord Jesus Christ is spoken during the liturgy. We also bow to the Cross as it passes by in the procession. And we bow a solemn bow at the Sanctus during the Eucharistic Prayer and after the Great Amen. There is also a custom to genuflect (bend the knee) toward the altar or tabernacle before entering one’s pew. These are certainly not requirements for Episcopalians, but they are powerful, ancient, biblically rooted, embodied practices that express our humility, love, and devotion to God. When I read the Gospel of John alongside the English and Anglican scholars, I not only see numerous invitations to embodied spiritual practice, but also an invitation to bow or genuflect at all expressions of the mystery of the Incarnation, including at those words Et Verbum caro factum est.

In his reflections on the Johannine prologue, The Venerable Bede writes, “[Christ] was born God from God, and he did not wish to remain only the Son of God; he deigned also to become Son of Man, not losing what he had been, so that by this he might transform human beings into sons of God and might make them co-heirs of his glory, and that by grace they might begin to possess what he himself had always possessed by nature.”[2] But to all who received him, who believed in his name, he gave power to become children of God.

McGinn concludes his 400-page tome with these words: “the Incarnation (‘enfleshment’) of the Logos [Word] in the person of Jesus Christ, the wandering preacher from Galilee, was directed from the start to bring about the equally astounding development that ‘humans could become the children of God’ (Jn 1:12-13). John’s essential message is clear: the Incarnation was always intended for human deification. Theosis is what it is all about…if there is one central message to take from this history, the unity of Incarnation and deification is it.”[3] God became human so that humans can become God. God participated in the human experience so that we can participate in the divine experience.

So, the soaring eagle of John lands among us, and when we receive the Word-made-flesh with the humility and reverence and love that is expressed and embodied in a simple or solemn bow or a genuflection, may we be prepared for the eagle to then carry us away on a life-long and everlasting journey of deification, making us to shine like the sun.

I invite you to experiment with bowing and genuflecting during the service and, after the final blessing today, I invite us to engage together in that ancient and medieval practice of “the Last Gospel.” After I offer the final blessing, I will read John’s prologue and, when we arrive at the “Word became flesh,” let us bow or genuflect as we are able and thus express, in our bodies, not only our humility and reverence for God but also the descent and ascent of the humble Christ who seeks to deify us. Amen.

[1] Gregory the Great (d. 604) correlates the two angels who sit at the head and foot of the empty tomb of Christ (John 20:12) with the cosmic beginning of the prologue (John 1:1 – 5) and the down-to-earth conclusion (John 1:14). The angel sitting at the head represents the Word that was with God and the Word that was God while the angel sitting at the foot represents the Word that became flesh. Gregory writes, “The feet can be understood as the mystery of the Incarnation by which divinity touches the earth because it takes on flesh…We kiss the Redeemer’s feet when we love the mystery of his Incarnation with our whole heart. We anoint his feet with ointment when we preach the power of his humanity with the good repute of holy speech.” Gregory the Great, Homilia 25.3, as cited in Bernard McGinn, In the Eagle’s Wake (New York: Crossroad, 2025), 171 – 172. In commenting on Job 37:6 in his Moralia, Gregory explains how John’s prologue simultaneously conveys the strength of the divine Christ and the weakness of the human Jesus: “Holy men preach the weakness of his humanity in order to pour into the hearts of their hearers the strength of his divinity…Let us hear through the thunder of the cloud the shower of strength: ‘In the beginning was the Word, etc.’ Let us also hear the shower of weakness: ‘The Word was made flesh and dwelt among us.’”

The Venerable Bede (675 – 735) contrasts John the Eagle who writes about the “eternity of the Word” with the Synoptics, which emphasize Christ’s humanity. In Homily I.8 (McGinn, Eagle’s Wake, 183), Bede explains that believers can “behold his humanity shining out with miracles and understand that his divinity was hidden within.” In Homily I.2, Bede explores what John means by seeing God (John 1:18), which is the highest grace promised to humanity (Matthew 5:8). For Bede, the promise expressed at the end of John 1 from Jesus to Nathanael about the heavens opening and angels ascending and descending upon the Son of Man (1:51) is already fulfilled since the angels ascending are the preachers who teach that in the beginning was the Word and the angels descending are the preachers who teach that the Word became flesh. “Thus,” McGinn writes, “the Northumbrian monk finds in the last verse of John 1 a key to interpret the significance of the whole first chapter of the Spiritual Gospel.” McGinn, Eagle’s Wake, 189.

John Scotus Eriugena (815 – 877) honors John the Evangelist as a “deified person” and almost divine figure and seems to almost equate the ascent of the “eagle” with that of the Evangelist: “John was not just a man, but more than a man…he could not have ascended into God unless he had first become God.” Homily Ch. V (McGinn, Eagle’s Wake, 196). Eriugena describes John 1:1-5 as “the mountain of theology” and verses 6 – 14 as “the valley of history.” McGinn explains, “The fact that Homily begins with John as the model of deification and ends with consideration of how the Incarnation enables us to become ‘children of God,’ shows that the basic theme of Eriugena’s reading of the Prologue is deification/filiation, becoming sons and daughters of God and co-heirs with Jesus, the unique Son of God by nature. In his homily on the prologue, Eriugena sees Peter, Paul, and John as representing three stages of ascent to God: Peter represents faith; Paul, understanding; and John, mystical contemplation. He also sees John as the angel ascending and descending on the Son of Man since he ascends by announcing the Word was divine and descends by proclaiming the Word was made flesh. The soaring Johannine eagle that descends and lands invites readers to be carried up to the heavens by the eagle as the Incarnation makes filiation and deification possible: “If the Son of God became man, which no one who receives him doubts, what wonder is there if someone who believes that he is the Son of God, is destined also to be a son of God?” Homily XXI. McGinn, Eagle’s Wake, 202.

[2] McGinn, Eagle’s Wake, 184.

[3] McGinn, Eagle’s Wake, 411.