Readings for the Feast Day of the Consecration of Samuel Seabury

This reflection was shared at the monthly gathering of Associates and Oblates of the Community of the Transfiguration on November 14, 2025

Today is not the Feast of Samuel Seabury. Today is the Feast of the Consecration of Samuel Seabury, which is an important distinction since Seabury was a slave owner and a British Loyalist during the American Revolution.[1] He wrote anti-Revolution tracts under the pseudonym “A Westchester Farmer” or A. W. Farmer, was arrested by patriots in 1775, was imprisoned for six weeks in Connecticut, and served as chaplain to the King’s American Regiment, a Loyalist regiment during the Revolutionary war.[2]

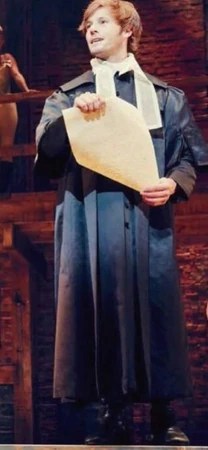

In the popular musical Hamilton, Seabury, as an Anglican rector, says, “Hear ye, hear ye! My name is Samuel Seabury, and I present ‘Free Thoughts on the Proceedings of the Continental Congress!’ Heed not the rabble who scream revolution, they have not your interests at heart…Chaos and bloodshed are not a solution. Don’t let them lead you astray. This Congress does not speak for me. They’re playing a dangerous game. I pray the king shows you mercy. For shame, for shame…”

By remaining loyal to King George III, Seabury sounded somewhat similar to the people of Israel in our reading from 1 Samuel, who say, “We are determined to have a king over us” (1 Samuel 8:19).

In the musical, Alexander Hamilton responds to Seabury, saying, “Yo! Chaos and bloodshed already haunt us, honestly, you shouldn’t even talk. And what about Boston? Look at the cost, n’all that we’ve lost n’ you talk about Congress?! My dog speaks more eloquently than thee! But strangely your mange is the same. Is he in Jersey?”

Even though it is an insult, I can’t help but appreciate Hamilton comparing Seabury to his dog since my beloved yorkie, born on this feast day, bears the name of this priest, who did indeed live in Jersey from 1754 to 1757, when he served as the rector of Christ Church in New Brunswick NJ.

Decades later, after the American Revolution, Seabury finally abandoned his loyalist leanings and was elected bishop of Connecticut after the people’s first choice for bishop (the Rev. Jeremiah Leaming) declined for health reasons. Just as the distinguished role of the twelfth apostle came down to two candidates—Justus and Matthias (as we read in Acts 1)—so too did the distinguished role of America’s first bishop come down to just two: Jeremiah Leaming and Samuel Seabury. In an alternate universe, my yorkie would be named “Jeremiah” or “Leaming,” but I’m glad Seabury was chosen since I think it’s a perfect name for my fur baby.

So, on March 25, 1783, Samuel Seabury was elected bishop by the clergy of Connecticut. However, he could not be consecrated bishop in England since that would require him, now a patriotic American, to take the Oath of Allegiance to the crown; and the English bishops refused to modify the liturgy for consecrating a bishop. It was in facing this dilemma that we see Seabury perhaps at his best. We see him displaying the virtue of “perseverance.”

In the now defunct Collect for the Feast of Samuel Seabury, we thank God for blessing His servant Samuel Seabury with “the gift of perseverance to renew the Anglican inheritance in the churches of North America.”[3] Seabury responded to a discouraging and disappointing reality not by giving up and yielding to despair but by thinking creatively and persevering. Bishop Mariann Budde writes, “Perseverance is the hidden virtue of every courageous life. Rarely do we see that it costs others to do what seems effortless to us. Nor do we know what it took for them to carry on when they were tired or discouraged or to start again after failure or disappointment. Wherever we find ourselves in relation to the decisive moments that set us on our life’s trajectory, perseverance is what enables us to keep going, even when we’re stumbling in the dark,” [4] even when the work is overwhelming and the laborers are few (Matthew 9:38).

In a decisive moment that set the entire Episcopal Church on its trajectory, Seabury travelled up north to Aberdeen, where the Nonjuring bishops of the Scottish Episcopal Church agreed to consecrate him bishop, under the condition that the Episcopal Church restore the epiclesis in its eucharistic prayer. The epiclesis is the priests’ invocation of the Holy Spirit so that the bread and wine may become the body and blood of Christ and although it was included in Cranmer’s 1549 Prayer Book, it was omitted from the 1552 and 1662 prayer books. The Scottish rite includes the epiclesis because they believe this practice, which they had borrowed from the Eastern Orthodox liturgy, was truer to the ancient pattern of Christian worship. “The Prayer Book of the new American church,” Christopher Webber points out, “would have links not only to Scotland but also to the Eastern Orthodox Church.” [5]

On November 14, 1784, Seabury became the first bishop (episcopus) of the Episcopal Church, essentially putting the “Episcopal” in the Episcopal Church,[6] and thus solidifying the future of an autonomous Anglican Church in the US that would forever change the meaning of “Anglican”[7]; all thanks to the perseverance of an imperfect person who worked creatively on behalf of a church with no bishops, a sheep without a shepherd (Matthew 9:36), to let the grace and goodness of God flow through him to bestow upon this church the gift of the episcopate.

[1] This Feast used to be dedicated to Seabury himself but about 15 years ago (2011), General Convention shifted the focus of the feast to Seabury’s consecration.

[2] As a British chaplain, Seabury had drawn maps for the British troops and was still receiving a pension from Great Britain in 1786.

[3] Collect for the Feast of Samuel Seabury: “Eternal God, who blessed your servant Samuel Seabury with the gift of perseverance to renew the Anglican inheritance in the churches of North America: grant us unity in faith, steadfastness in hope, and constancy in love, that we may ever be true members of the body of your Son Jesus Christ, who is alive and reigns with you in the unity of the Holy Spirit, one God, now and forever. Amen.”

[4] Mariann Edgar Budde, How We Learn to Be Brave: Decisive Moments in Life and Faith (New York: Avery, 2023), 162.

[5] Christopher L. Webber, Welcome to the Episcopal Church: An Introduction to Its History, Faith, and Worship (Harrisburg PA: Morehouse, 1999) 9.

[6] In 1780, priest and college provost William Smith of Maryland began convening gatherings of clergy and laity; and by 1783, they had chosen the name “Protestant Episcopal Church” to replace the no longer favored Church of England as the name of their denomination. “The word protestant differentiated the church from the Roman Catholic Church and the word episcopal was the name for the seventeenth-century English church party that favored retention of the episcopacy.” Prichard, 114.

[7] John L. Kater, Ministry in the Anglican Tradition from Henry VIII to 1900 (Lanham MD: Fortress Academic, 2022), 113.