The Zen of St. Francis: An Episco-Bu-Jew’s Reflections on the Poverello

This presentation was given at Ensō Village, Zen-inspired Retirement Community in Healdsburg CA as part of the Speaker Series on Wednesday October 8, 2025.

It’s a joy and honor to be here and I’d like to thank my friend Kogen for inviting me. You are all very lucky and blessed to have Kogen as your Director of Spiritual Life. Eight years ago, I invited Kogen to guest preach at the Episcopal Church of the Redeemer in San Rafael for the Second Sunday of Advent and he preached an excellent sermon titled “Bring Your Own Jingle Bells” which you can actually listen to on YouTube. I highly recommend it!

Today, I’d like to talk about St. Francis of Assisi for two reasons: first, because his feast day was just four days ago (Oct 4) and we Episcopalians celebrate his feast day by blessing people’s animals. We hosted three separate Animal Blessings this last weekend: one at a transitional housing community, one at a parishioner’s home, and one at church.

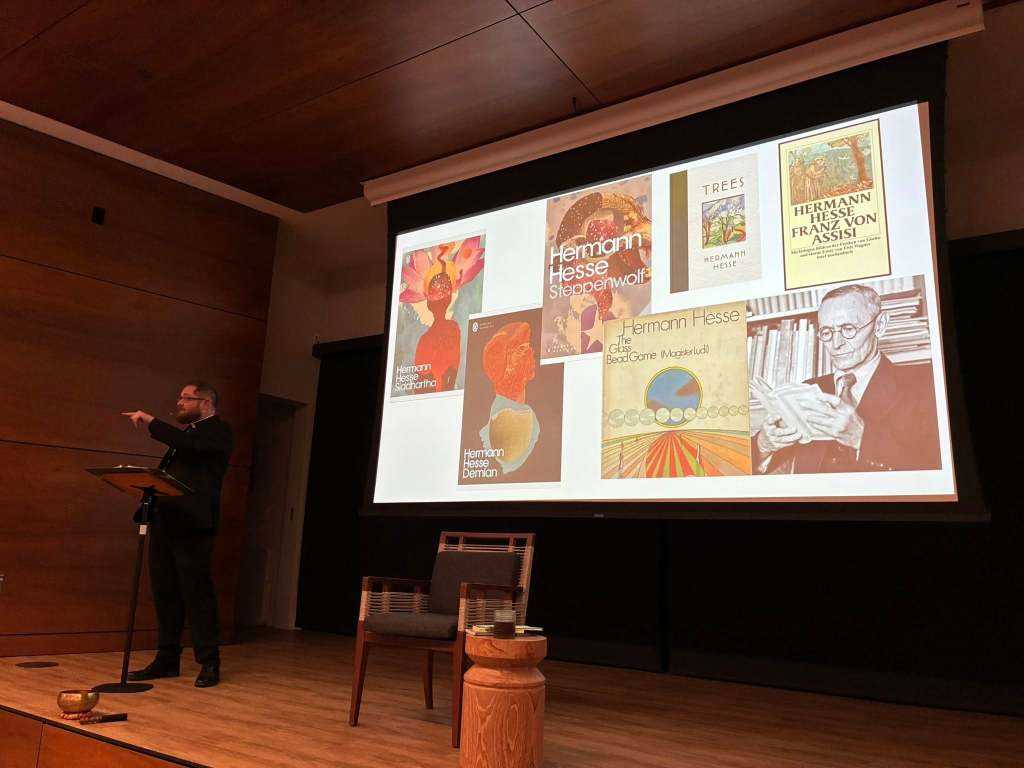

The second reason I’d like to talk about Francis is because I’ve been translating and annotating a short monograph about St. Francis written in 1904 by the Swiss German author Hermann Hesse. I imagine some of you have heard of or read some books by Hesse, who is most well-known for writing Siddhartha, and Demian, and Steppenwolf. Both Siddhartha and Demian were especially formative books for me as I was breaking free from the Evangelical Christian world in which I grew up.

A little background about myself: I attended a small liberal arts college in Santa Barbara called Westmont and during my Junior Year, I left Christianity for a period while attending two off-campus programs, one in southern Oregon and one in San Francisco, where I served as a multifaith chaplain at the General Hospital (now the Zuckerberg Hospital). The chaplain supervisor, who later told me I was called to be a minister, initially called me an “unidentified spiritual pilgrim.” Ane I always resonated with Hermann Hesse’s words from his book Demian, in which he says,“I have been and still am a seeker, but I have ceased to question stars and books; I have begun to listen to the teaching my blood whispers to me.” While seeking that inner teaching, I still sought wisdom from books; and along with Hesse’s books, I was reading the Dhammapada, the Tao Te Ching, the Bhagavad Gita, the Koran, and the poetry of Rumi and Dogen (who were both contemporaries of St. Francis).[1] I found so much refreshing wisdom in these texts, which filled me with wonder and curiosity; and at the same time, they reminded me of the wisdom of that wild Jewish Mystic named Rabbi Y’shua HaNotzri (or Jesus of Nazareth), who shared similar insights in his own edgy Jewish way. I returned to the Gospels and began reading them with the same posture in which I was reading these other sacred texts, eschewing the pre-packaged interpretations of Jesus’s teachings that I had inherited from my Evangelical upbringing. And when I did this, Jesus quickly began to sound like the most enlightened guru and most earthy mystic of them all!

While living in San Francisco, I was assigned to visit different churches and write about my visits. The first “church” I visited was the San Francisco Zen Center, which upset my professor a little bit since it’s not technically a church, but that’s where the Spirit was leading me at the time. The second church I visited was St. Gregory of Nyssa Episcopal Church in Potrero Hill, where I was introduced to the radical openness of the Episcopal/Anglican tradition. This congregation expresses Anglican openness beautifully with their vast wrap-around icon of the Dancing Saints in their rotunda, an icon that includes Saint John Coltrane dancing with his saxophone, Rumi, Abraham Heschel, Anne Frank, Thomas Merton, Nicholas Black Elk, Lady Godiva in her birthday suit, Desmond Tutu, Chinese poet Su Shi and, of course, St. Francis dancing with the wolf of Gubbio. However, the most central and prominent dancer, who is framed by a mandorla, is Jesus of Nazareth. This is when I learned that the Episcopal Church is not only radically open to a colorful cornucopia of saints and diverse sources of wisdom, but also grounded firmly in Christ, and deeply rooted in ancient liturgy and tradition. I felt like the Episcopal Church was a community that would allow me to grow like a tree with roots planted deep and firm in the Christian tradition and with branches that could spread out wide enough to learn from and connect with other faith traditions. Just as Thomas Merton identified as a true Jew under his Catholic skin, I felt like I could freely practice Buddhist mindfulness and incorporate Jewish spirituality (which whispers in the Jewish blood I inherited from my father) as a BuJew under my Episcopal skin. This openness and rootedness helped me to discover what Thomas Merton and Hermann Hesse seemed to discover in their own way: that much of the spiritual wisdom I was seeking outside of Christianity, in Buddhism or elsewhere, was actually waiting for me within the vastly diverse and rich Christian tradition. When Merton asked the Hindu monk Brahmachari which books he’d recommend for spiritual growth, Brahmachari did not tell him to read the Vedas or the Bhagavad Gita but rather encouraged him to read the texts of his own beautiful tradition: The Imitation of Christ by Thomas á Kempis and the Confessions of St. Augustine. While Hesse is well known for bridging the East and West with Siddhartha and Journey to the East, his monograph on St. Francis reveals his appreciation for Christianity and the profound, Zen-like wisdom of the Italian saint.

One particular stream of Christian thought that I have found particularly life-giving and generative is the tradition of the Christian mystics who offer specific spiritual practices that can help us connect with our true selves and the divine source. The medieval English mystic known as the Cloud author wrote a treatise on Christian meditation and Centering Prayer titled The Cloud of Unknowing, which I distilled in accessible language for my congregation, and which has been published as The Cloud of Unknowing Distilled. And I’d like to read a brief section from the introduction:

“Mystics are members of faith communities that have peered under the stones of their tradition’s doctrines and dogmas to discover the rich soil of direct spiritual experience. By delving deep into the radical roots of their own religion, mystics all seem to be tapping into a similar, if not identical, source. Although their faith traditions might appear to be drastically different on the surface, mystics all seem to be drinking from the same well. They may draw from different stories and use different symbols, but they all seem to be speaking in a similar language to describe a shared experience.

By delving deep into the roots of his own tradition, the Cloud author ends up sounding almost like a Zen master or a teacher of Transcendental Meditation or the Taoist philosopher Lao Tzu, with poetic and enigmatic statements like ‘Be the wood, and let the [meditation] be the carpenter,’ ‘Pray nowhere,’ and ‘God is your Being.’ In this way, mystical literature can offer a path for interreligious learning, dialogue, and growth, especially across the spiritual traditions of the East and West.”[2]

The spiritual practice of the Cloud author has become known today as Centering Prayer and, put most simply, it involves choosing a sacred word such as “love” or “peace” or “God” or “Abba” and using that word to let go of thoughts and connect with the heart. When distractions come as they inevitably do, the invitation is to simply return to the sacred word. Practitioners recommend doing this twice a day for at least 20 minutes at a time. While the Cloud author was writing in the 14th century, this spiritual practice has roots that stretch all the way back to the Desert Fathers and Mothers of Egypt and Palestine in the 4th and 5th centuries and perhaps all the way back to the practitioners of Merkabah Mysticism, a form of Jewish mysticism likely practiced by St. Paul and Jesus himself.

Another saint who seemed to practice this form of prayer to some extent (or at least a version of this prayer) was St. Francis of Assisi. In an anthology of short stories called The Little Flowers of Saint Francis[3] written in the 14th century (same century as The Cloud), there’s a story about Francis’s friend Bernard inviting the saint over to his home for a night to give him some respite from the many insults and attacks he was receiving from the townsfolk while he was sleeping outside. Bernard pretended to fall asleep by snoring loudly and that’s when Francis got out of his bed and began praying “My God, my God” over and over again, weeping in the darkness until the first light of day. This prayer was his only prayer that night, “My God, my God…” and in it he became caught up in wonder and in deep contemplation of God’s love. Some accounts record him saying, “My God, my all,” but either way, he seemed to be using a sacred word or phrase to fill his heart with God’s love; and we would pray all through the night.

Centering Prayer is a spiritual discipline that I try to practice on a fairly regular basis and my parish offers a weekly Centering Prayer group that meets every Tuesday night at 6:30 PM, when we gather in our Chapel for a brief reading and discussion, followed by 30 minutes of practice.

The other spiritual discipline that St. Francis practiced (and I try to practice) was one referenced in the previous story. He loved to pray outside; and not just outside, but in the forests and among the trees. The friars are frequently described as praying and contemplating in the woods, sometimes pouring out their tears, sometimes sighing and crying aloud, sometimes rapt in ecstasy with an army of saints and angels, and sometimes celebrating Mass. Francis’s first modern biographer Paul Sabatier (1854 – 1941) wrote that the “pure air of the forest must have been good for his physical well- being.” In Chapter 11 of Hermann Hesse’s monograph on Francis, he writes,

“Although he hated idleness and devoted all his strength to serving his neighbor, Francis’s heart was extremely sensitive and tender, and he suffered deeply every day at the sight of human misery. Whenever he felt overwhelmed, he would retreat into quiet solitude so that his weary heart could rest and be revived by the Source of life.

“Through consistent practice, Francis had become an unparalleled master in that wonderful and glorious art which only the poets and saints have truly learned: the art of renewing oneself daily through encounters with nature and through intimacy with the life-giving powers of the earth. Like a child or wise elder, he spoke to the flowers, the fronds, the ripples in the river, and all the diverse creatures of the land. He sang songs of praise to them and with them; he consoled them and rejoiced with them, sharing in the pure blessedness of their lives. God had generously given Francis the gift of a heart that would not age, but which would remain as fresh and full of wonder as a child’s, throughout his entire life. A true and genuinely pure heart is like the magical secret of King Solomon that reveals the language of animals and the inner nature of plants, flowers, stones, and mountains so that the immense diversity of creation unfolds before one’s eyes as a unified whole, without any fissures, rifts, or schisms. As one favored by God, Francis understood the beauty of the earth as few poets ever have. He loved every creature, great and small, and they would respond by loving him back. When he was tired of talking to people, he would go off into the meadows, the forests, and the valleys, and listen to the sweet and inspiring language of paradise in the springs, the breeze, and the bird’s song. He knew full well that nothing on earth is without a soul; and he approached each element of creation with reverence and brotherly love, whether it be a stone or a simple blade of grass.”

St. Francis was a medieval practitioner of Nature and Forest Therapy, which is a real practice today based on the Japanese practice of Shinrinyoku[4] or Forest Bathing. In the 1980s, Japanese scientists found that exposure to trees and their phytoncides served as an effective eco-antidote to urban and technological burnout. Rooted in their Shinto and Buddhist practices, they began encouraging people to bathe in the phytoncides of the forests. When we breathe in these phytoncides which the trees release, our bodies respond by increasing the number and activity of the white blood cells called natural killer cells, which kill tumor-infected and virus-infected cells. Phytoncides also reduce our cortisol levels,[5] temper inflammation, improve cognition, enhance sleep, relieve anxiety and depression, help regulate blood pressure, and even boost empathy. According to the early accounts of St. Francis and the friars, they were forest bathing. Or perhaps more appropriately, they were forest praying.

One of my favorite spiritual practices has been celebrating the Holy Eucharist outside among the redwoods with parishioners in what we call “Sacred Saunters.” A few years ago, I was certified as a Forest Therapy Guide through the Association of Nature and Forest Therapy, founded by a man named Amos Clifford, who was deeply influenced by Zen meditation. I incorporate elements of Forest Therapy into the Sacred Saunters, especially invitations to engage with our five bodily senses as well as our heart sense;[6] and to be fully present by reflecting on the simple question, “What are you noticing?”

These practices not only have roots in Franciscan spirituality, but also in the person who inspired Francis in the first place: his Lord and Savior Jesus Christ who also loved being outside and among the trees! Jesus said, “Look at the birds of the air! See how the lilies of the field grow!” (Matt 6:25 – 34); “Notice the sparrows” (Matt 10:20) Watch how the Sower sows his seed. Listen to the wind (John 3), Look at the healing power of this mud I just made! And Jesus loved talking about trees. He says, “Look at the fig tree! Look at all the trees!” (Luke 21:29). In fact, just this last Sunday, the Sunday when many Episcopal congregations were celebrating the Feast of St. Francis, Jesus said, “If you had faith the size of a mustard seed, you could say to this mulberry tree, ‘Be uprooted and planted in the sea,’ and it would obey you.” (Luke 17:6). It’s important to note that Jesus says “this mulberry tree” (te sukamino taute), which means he is not talking about some abstract tree but rather a particular tree that stands right in from of him and his disciples, which they can see and touch and smell and taste (mulberries are a good source of iron and vitamin C) and hear (psithurism: the word for the whispering sound of wind blowing through tree branches). Jesus, who loves talking about trees, is speaking hear about having a conversation with a tree! A conversation in which the tree listens! When the text says that the tree will obey you, the word is actually hupekousen, which means “listen.” If you have just a little faith, you can have conversations with trees and other creatures, and they will listen to you!

St. Francis knew this well. One day when he was preaching at a castle called Savorgnano, there was a kettle of swallows singing and making noise in the courtyard. So, he told them to be silent until he had finished preaching to the people, and the swallows listened to him and obeyed him. Another day, when he was walking cheerfully in the region near Bevagna, he looked up and saw a huge flock of birds perched on the trees along the path. He then turned towards his companion friars and said, “Wait for me here on the road, I want to go preach to my beloved bird brothers.” So, he went into the field and began preaching to the birds, who immediately approached him and remained very attentive until he had finished his sermon, flying away only after he gave the final benediction. And Br. Masseo saw that as St. Francis was speaking to them, all the birds opened their beaks, stretched out their necks, spread their wings, and bowed their little heads to the ground in a gesture of humble gratitude; and then they let him know through their chirping that he had brought them great joy. And St. Francis took delight in each of them and praised the Creator, whom he saw within them. St. Francis had the kind of faith that inspired him to converse with creation and that inspired creation to listen to him. He had faith that could move mountains and uproot trees.

Here’s a little eco-theology inspired by Jesus and Francis. As human beings who have faith that we are made in the image of God our Creator, we Christians believe we have been given a unique power and authority over creation. In Genesis chapter 1, God says, “Let us make humankind in our image and let them have dominion over the creatures of creation” (1:26). We do indeed have power to uproot trees and move mountains. In fact, some trees were, in a sense, “uprooted” to construct the buildings here in this lovely village. However, before we get carried away with this power to manipulate creation, Jesus immediately follows his teaching on uprooting trees with one of the most extreme parables about selfless and humble service to God, about a servant working in the field all day and then preparing supper for their boss and saying, “I’m an unprofitable servant. I have done only what I ought to have done.” Here, Jesus is making it abundantly clear that the only proper way to understand our God-given power and authority as bearers of the divine image and as “rulers” of creation is within the frame of selfless humble service to God. It is within this frame, that the idea of being a ruler of creation transforms so much that it begins to make much more sense to call ourselves caretakers rather than rulers. And if we look at the Hebrew word for “dominion” which is radah, we learn that it is associated not at all with a tyrannical ruler who uses his subjects for selfish gain and exploitation but rather with a benevolent ruler who walks among her people, who listens to them, cares for them, and seeks ways to humbly serve them. That is what it means when God says in Genesis that we are to have “dominion” over creation. We are to tend and till and care for all of God’s creation (as God mandates in Genesis 2:15).

Not only did Saint Francis have faith that the trees and birds and other creatures would listen to him and obey him, but he also had enough humility as a servant to listen to them, as a benevolent ruler listens to her people. This is the Zen of St. Francis and this is why St. Francis is the great patron saint of creation because he knew how to listen to creation as a humble servant. He would never tell a tree to be uprooted without first listening to it and receiving its permission.[7]

There’s a story of a Zen master who was a carpenter (as Jesus was) and whose tables and chairs were praised for their ineffable quality. When asked how he made them, he said, “I go into the forest and talk to the trees and ask which ones are ready and willing to be made into chairs.”[8] And Thich Nhat Hanh tells a Zen story of a student who felt he had not yet received the deepest essence of his master’s teaching. So, when he asked his master about this, the teacher replied, “On your way here, did you see the cypress tree in the courtyard?” Thich Nhat Hanh explains that the master was teaching that if we walk past a cypress tree and don’t really see it, then when we arrive in front of our teacher, we won’t see our teacher either. We shouldn’t miss any opportunity to really see the cypress tree. What is the cypress tree on the path you take to work every day? If you cannot even see the tree, how can you see your loved ones? How can you see God?[9] And if we cannot listen to the trees, then how can we listen to God?

The Buddhist practice of ordaining trees may be seen as an expression of this kind of listening, in which Buddhist monks wrap trees in saffron robes in order to consecrate them and protect them from deforestation. One might also see this kind of listening conveyed in the Jewish holiday of Tu B’shvat, the New Year for Trees (Rosh HaShanah La’llanot).

Finally, Roman Catholic author of numerous books on St. Francis, Jon M. Sweeney wrote, “I sometimes imagine Francis in conversation with a Zen master. It feels entirely plausible. For example, the Zen poet Dōgen Zenji lived in the same half-century, albeit across the world in Japan.

Dogen inquires, Where do you live?

Francis says, Here and there.

What do you mean, here and there.

I move around a lot.

Why is that?

We don’t build houses. We don’t even plan tomorrow’s menu.[10]

Why not? Are you in a hurry?

Not exactly, but there’s no telling where we should be next year, or tomorrow.

So you could simply settle into another home wherever you go tomorrow.

I don’t think so. If I’m building, I’m unable to listen.[11]

St. Francis knew he had the power to make creation listen to him and obey him, but he preferred to be the one listening. It is this attitude that inspired the great “Prayer of St. Francis”; and although Francis never wrote this beautiful prayer (which was written in the early 20th century), it has roots in the famous saying of Francis’s close companion and disciple, Blessed Giles of Assisi who said, “Blessed is the one who loves and does not therefore desire to be loved; blessed is the one who serves and does not therefore desire to be served; and blessed is the one who listens and does not therefore desire to be listened to.”[12]

I see the invitation to emulate the Zen of St. Francis not so much in believing in our power to uproot trees but more in heeding our call to serve with humility and in listening to the birds and trees and mountains and all of creation with the tender care and compassion of the little poor man, the Poverello of Assisi, who said, “I have done only what I ought to have done. May Christ teach you what is yours to do.” The Zen of St. Francis can also be emulated through prayer: through Centering Prayer, using a sacred word or phrase like “My God, My all,” through forest prayer, like Sacred Saunter Outdoor Eucharists or other forms of outdoor worship, and through praying the Prayer of St. Francis, which I invite you to pray with me now, insofar as you feel comfortable doing so:

Lord, make me an instrument of your peace:

where there is hatred, let me sow love;

where there is injury, pardon;

where there is doubt, faith;

where there is despair, hope;

where there is darkness, light;

where there is sadness, joy.

O divine Master, grant that I may not so much seek

to be consoled as to console,

to be understood as to understand,

to be loved as to love.

For it is in giving that we receive,

it is in pardoning that we are pardoned,

and it is in dying that we are born to eternal life. Amen.

[1] See Steve Kanji Ruhl, Enlightened Contemporaries: Francis, Dōgen, and Rūmī: Three Great Mystics of the Thirteenth Century and Why They Matter Today (Rhinebeck NY: Monkfish Book, 2020).

[2] Daniel London, Cloud of Unknowing Distilled (Hannacroix NY: Apocryphile Press, 2021),viii – ix.

[3] The Little Flowers is an anthology of 53 short stories about the life of St. Francis of Assisi and the first generation of Franciscan friars. Although the stories are not historical accounts of St. Francis, they remain genuinely Franciscan, revealing a flavor of the Franciscan movement that thrived during the end of the 14th century. Most scholars are now agreed that the author was Ugolino Brunforte (c. 1262 – c. 1348). This account of St. Francis praying “My God, my God” is recorded in Chapter 2 of The Little Flowers.

[4] In the word Shinrin (forest)the “r” is pronounced like our “d.”

[5] Cortisol is the body’s main stress hormone.

[6] According to Francis scholar Jon M. Sweeney, St. Francis “did not ‘put a curb upon his senses,’ as one early account puts it. He would never disdain the created world.” Jon M. Sweeney, Feed the Wolf: Befriending Our Fears in the Way of Saint Francis (Minneapolis: Broadleaf Books, 2021), 87. The early account he is referencing is Bartolomew, Francis of Assisi: Early Documents, vol 4, bk. 1, 238.

[7] After a rainfall, St. Francis would carefully pick up earthworms from the road and move them to safety in the grass so they would not be trampled or die in the sun.

[8] Osho, A Sudden Clash of Thunder.

[9] Thich Nhat Hanh, The Art of Living: Peace and Freedom in the Here and Now, “The Cypress in the Courtyard” in Chapter 3: Aimlessness: Resting in God.

[10] Dõgen would have understood this very well. In Dōgen’s Shōbōgenzo Zuimonki, he instructs, “Do not make arrangements in advance for obtaining your clothing and food. If all the food is gone, then you may go out and beg for some. To make plans in advance to beg for food from certain persons is like storing up provisions, which violates the Buddhist regulations. Monks are like the clouds and have no fixed abode. Like flowing water, they attach themselves to nothing. Even though monks possess nothing but their robes and bowl, if they rely on even one donor or on one household of relatives, they and those upon whom they rely become enmeshed, and the food is thus unclean.” Dōgen, Shōbōgenzō Zuimonki, V. 21, translated by Reihō Masunaga, A Primer of Sōtō Zen: A Translations of Dōgen’s Shōbōgenzō Zuimonki (Honolulu HI: East-West Center Press, 1971).

[11] Jon M. Sweeney, Feed the Wolf: Befriending Our Fears in the Way of Saint Francis (Minneapolis: Broadleaf Books, 2021), 175 – 176

[12] Giles of Assisi, The Golden Sayings of Blessed Brother Giles, translated by Paschal Robinson (Dolphin Press, 1907), 5.