Readings for the Feast Day of St. Bernard of Clairvaux (1090-1153)

This sermon was preached at Christ Episcopal Church at the Chapel of Our Merciful Saviour in Eureka CA on August 20, 2025.

While the era of the Church Fathers generally spans from the first century to the seventh century AD, St. Bernard of Clairvaux, who lived in the 12th century, about 500 years after this patristic era, is known as the last of the Church Fathers, thus making him perhaps the most authoritative theologian of the High Middle Ages. If that is too grandiose a title, then we can say with more conviction and certainty that he was the most authoritative and influential church leader of the twelfth century. Thomas Merton said that “Bernard contained the whole twelfth century in himself.”[1] He convinced hundreds of men to join the monastery with his eloquence and piety while founding 68 monasteries in the process. One of these men whom he convinced to join the monastery later became the pope: Pope Eugenius III. Secular rulers throughout Europe sought his guidance and wisdom and often asked him to settle disputes. He criticized the emerging scholastic movement which applied a reductionistic rationalism to the ineffable mysteries of God, which he often preferred to express through poetic imagery and songs like “O sacred head, sore wounded,” a beloved hymn that he wrote and which we still sing today. Although considered one of the most revered saints and mystics of church history, he was not without his faults. Not only did he permanently damage his body through his extreme forms of fasting and self-denial, he also was the spiritual leader and charismatic preacher of the Second Crusade, which turned out to be disastrous.[2] Thomas Merton writes that it is in his passionate involvement with the violent Crusades “that we see Bernard, the saint, as a most provoking enigma, as a temptation, perhaps even as a scandal.”[3]

This morning, I want to highlight a different kind of scandal which St. Bernard expressed and embodied masterfully; and that is the scandal associated with the first reading appointed for his feast day, the reading from the Song of Songs. I am referring to the scandal of erotic mysticism, a form of Christian mysticism that St. Bernard mastered perhaps better than any other male mystic of the church.[4] St. Bernard found his inspiration in the Song of Songs, a biblical poem narrated mostly by a woman celebrating the sexual intimacy between her and her lover who are not yet married.[5] This poem, which scandalizes Puritans, serves as the great fount of Christian and Jewish erotic mysticism, a mysticism that uses sensual imagery to express our union with the divine.[6] The great Rabbi Akiva said, “All of Scripture and its texts are holy, but the Song of Songs is the Holy of Holies.”[7] St. Bernard understood this, which is why he preached over 85 sermons on this one book, devoting multiple homilies to single words and phrases. Because he was able to draw so much meaning out of each word and image and he loved to linger with them, his sermons only covered two of the eight chapters of the Song of Songs.[8] Bernard preached nine homilies on the first line of the poem: “Let him kiss me with the kisses of his mouth.”

St. Bernard uses “the kisses” to explain different stages of spiritual growth. Our spiritual journey begins with what he calls “the kisses of the feet.” When we initially seek forgiveness of sin and amendment of life, we are kissing the feet of Christ. When we grow in spiritual wisdom and illumination, we begin to kiss the hands of Christ. And it is not until we receive the rare gift of perfect union with Christ that we dare to kiss our Lord on his very mouth and be kissed by him in return.[9]

Bernard then uses the image of the kiss to explain the Trinity, saying, “The Father kisses. The Son is kissed. The Holy Spirit is the kiss.”[10] St. Augustine referred to the Holy Trinity sometimes as the Lover, the Beloved, and the Love Overflowing, but St. Bernard described the Holy Trinity as “The One who Kisses, the One who is Kissed, and the Kiss Itself.”

I have suggested that we think of the sacraments as kisses from God. A kiss is an outward sign of an inward love, but it is also more than that: a kiss is an active expression of that love. And sometimes a kiss can say “I love you” much more effectively than simply saying the words. A kiss can be the words “I love you” made flesh. In a few moments, we will partake of the sacrament of Holy Eucharist in which we receive the Body and Blood of Christ in our bodies through our mouths. St. Bernard of Clairvaux, who has been cited as saying “the Eucharist is that love which surpasses all loves in Heaven and on earth,” invites you today (on his feast day) to receive the consecrated elements as a kiss directly from God, as a foretaste of that perfect, mouth-to-mouth mystical union with Christ. May we not be scandalized by the sexualized language of mysticism, which dates all the way back to our ancient texts. Rather, may we join in that chorus sung by Jewish Mystics and Christian saints throughout the centuries, spurred on by great choir leaders like Bernard of Clairvaux, singing with them, “Let God kiss me with the kisses of his mouth!” Amen.

[1] Thomas Merton, The Last of the Fathers (San Diego: Harvest, 1982), 23.

[2] St. Bernard is also considered to be the spiritual leader and one of the founders of the Knights Templar.

[3] Thomas Merton, The Last of the Fathers (San Diego: Harvest, 1982), 40.

[4] The female mystics likely surpassed him, but no male mystic surpassed him, except for those outside of the church, like the Sufi Mystic Rumi of the Islamic tradition.

[5] Will Durant said that the presence of the Song of Songs “in the Bible is a charming mystery: by what winking – or hoodwinking – of the theologians did these songs of lusty passion find room between Isaiah and the Preacher [Ecclesiastes]?” Our Oriental Heritage, 341, as quoted by Bernard Bangley, Talks on the Song of Songs: Bernard of Clairvaux, x.

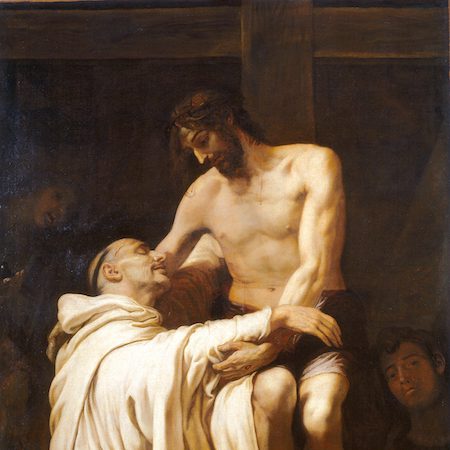

[6] St. Bernard had visions in which he was drinking milk from St. Mary’s breasts and drinking blood from Jesus’s side, visions that have been portrayed by 17th painters.

[7] https://www.sefaria.org/sheets/113750?lang=bi

[8] After he died, two English Cistercian abbots Gilbert of Hoyland and John of Ford wrote homiletic commentaries on the remaining chapters of the Song of Songs.

[9] Bernard of Clairvaux, Song of Songs Sermon 4, edited and modernized by Bernard Bangley, Talks on the Song of Songs, 6. In his treatise “On Loving God,” Bernard described the following four stages of love: loving ourselves for own sake; loving God for our own sake (which may align with the “kiss of the feet”); loving God for God’s sake (which may align with the “kiss of the hand”); and loving self for God’s sake (which may align with “the kiss of the mouth.”)

[10] Bernard of Clairvaux, Song of Songs Sermon 8, edited and modernized by Bernard Bangley, Talks on the Song of Songs, 14.