Readings for the Third Sunday in Lent (Year C)

This sermon was preached at Christ Episcopal Church in Eureka CA on March 23, 2025.

Our readings for this Third Sunday in Lent explore the mystery of suffering in a world that we believe was created, according to the Nicene Creed, by God “the Father Almighty,” a phrase we discussed this last Tuesday. From biblical times until now, theologians have struggled to reconcile faith in a loving and all-powerful God with the reality of suffering. How could God be all-powerful and all-loving and yet permit so much evil?

In our reading from Exodus, we learn that God hears the “cry of the Israelites” and tells Moses, “I know their sufferings, and I have come down to deliver them” (Exodus 3:7); so, go down, Moses, way down in Egypt’s land; tell old Pharaoh to let my people go. In this classic and foundational story of liberation, the Almighty and all-loving God refuses to permit evil and thus empowers Moses to rescue his people from suffering. Inspiring stories like this give us hope amidst our suffering, but what about all the other horrific tragedies and genocides throughout history which God seems to permit?

The classic Christian answer to the problem of suffering is that God gave us free will; and when we choose to sin, we inevitably bring suffering upon ourselves and others. We see this popular theology expressed in Paul’s first letter to the Corinthians, when he explains that some of the Israelites suffered death and were destroyed by serpents because they put God to the test or because they complained too much. This theology is prevalent throughout Scripture and our Christian tradition: suffering is the result of sin, so if we are suffering, it is most likely because of our sin.

However, in today’s Gospel, Jesus challenges and complicates and even seems to reject elements of this theology. Although Jesus knows that sin does indeed lead to suffering, he strongly warns against assuming all victims of suffering deserve their suffering because of their sin. Yes, 2 + 2 = 4, but 4 isn’t always the result of 2 + 2; 4 can also be the result of 73 – 69.[1] Jesus references a freak accident, the collapse of the Tower of Siloam which tragically killed 18 people and then asks, “Do you think these people who were killed were especially sinful people who deserved that kind of death? Do you think that God was punishing them?” Jesus answers these questions with an emphatic “NO!” The Greek word for “no” is ou but Jesus says ouki, which in Greek emphasizes the word to become “Absolutely not!”[2]

He then calls his listeners (including us) to repent; and the actual meaning of the Greek word that Jesus uses for “repent” in Luke (metanonte) is literally, “change your mind; change your way of thinking; change your theology.” In this context, Jesus is clearly saying, “Stop assuming victims deserve their suffering.” When we see suffering in others, we must not automatically deduce that they did something to deserve it. In fact, suffering in others might be more connected to our own sins than we like to think. For examples, environmental scientists point out the sobering fact that our health and wealth and privilege come at the expense of other people’s sufferings around the globe. When we point the finger at the victim, we are pointing always three fingers back at ourselves.

When Jesus says, “Unless you repent, you will all perish as they did,” he is saying that if you remain stuck in your victim blaming and perpetuate this way of thinking, then other people will likely blame you when you experience inevitable suffering in your own lives. And then Jesus drives home this point with a parable; and yes, it’s a parable of a tree because Jesus loves talking about trees. No matter what the subject is, he’s going to find a way to bring it back to trees. It’s not your priest who’s obsessed with preaching about trees, it’s Jesus!

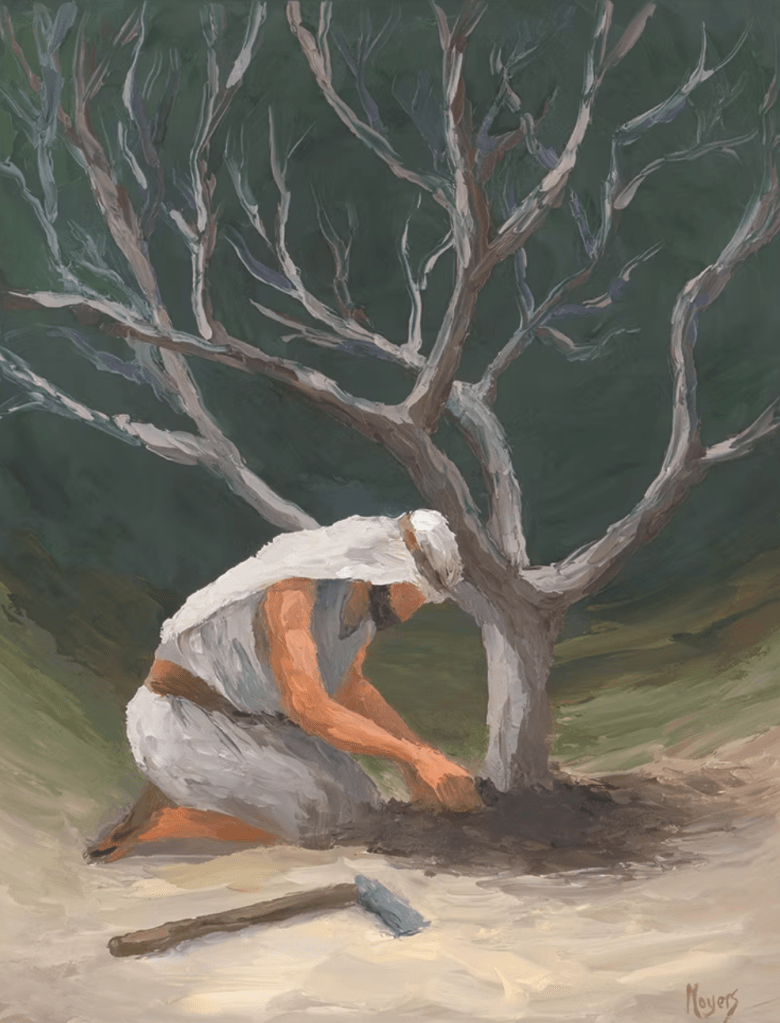

In this parable, there is a fig tree, a man, and a gardener. The man sees the fig tree not producing any fruit and thus assumes that the tree must be inherently bad: “It’s the tree’s fault! It’s wasting soil and important resources that ought to be used on more productive trees.” It never once crosses the man’s mind that maybe he might be responsible for helping the tree produce some fruit. Maybe he could do a little bit more than just point out its faults in order to justify its destruction. The gardener wisely suggests, “How about we give it some love and care and attention and see what happens.” An expert in his trade, the gardener is confident that the tree will be fruitful when given some loving attention, so confident that he can say, “If it doesn’t bear fruit in a year, cut it down.” He can say this because he knows it will indeed bear fruit. The man in the parable who blames the tree is not God. The man is us whenever we see someone suffering and assume that they are getting what they deserve. God is not the man in the parable. God is the gardener; and God invites us to be gardeners as well. God invites us to see suffering in others as an opportunity to offer compassion and nourishment, prayer, care, and attention.

In the Nicene Creed, we also confess that Christ will come again in glory to judge the living and the dead. We believe that all sinners—including the self-righteous who insist that they don’t sin at all—will stand before the judgement seat of Christ. But our job is not to judge. In the face of suffering, I personally find all theological defenses ultimately inadequate, but the most dangerous theological defenses are those that make us feel righteous in our judgment and condemnation of those who are suffering. Jesus calls us to repent by changing our minds and our theology so that we can judge less and care more, like the gardener in the parable, knowing that Christ is always tending to each of us with the tender compassion of the most patient gardener and lover of trees. Amen.

[1] “Yes, 2 + 2 = 4, but 4 doesn’t always equal 2 + 2; it can also equal 73 – 69.” Gary Commins, Evil and the Problem of Jesus (Cascade Books: Eugene OR, 2023), 65.

[2] In the Gospel of John, the same word “Siloam” appears within a similar context regarding the question of suffering and its victims. The disciples ask Jesus, “Who sinned this man or his parents that he was born blind?” (9:2). Again, Jesus invites his disciples to stop assuming victims deserve their suffering and then he invites the man born blind to wash his muddy eyes at the pool of Siloam, where he is healed (9:7).