Readings for the Twenty-Third Sunday after Pentecost (Year B – Track 1 – Proper 25)

Job 42:1-6, 10-17

Psalm 34:1-8, (19-22)

Hebrews 7:23-28

Mark 10:46-52

This sermon was preached at Christ Episcopal Church in Eureka CA on Sunday October 27, 2024.

May the words of my mouth and music of all our hearts be pleasing to you, O Lord, our strength and our liberation. Amen.

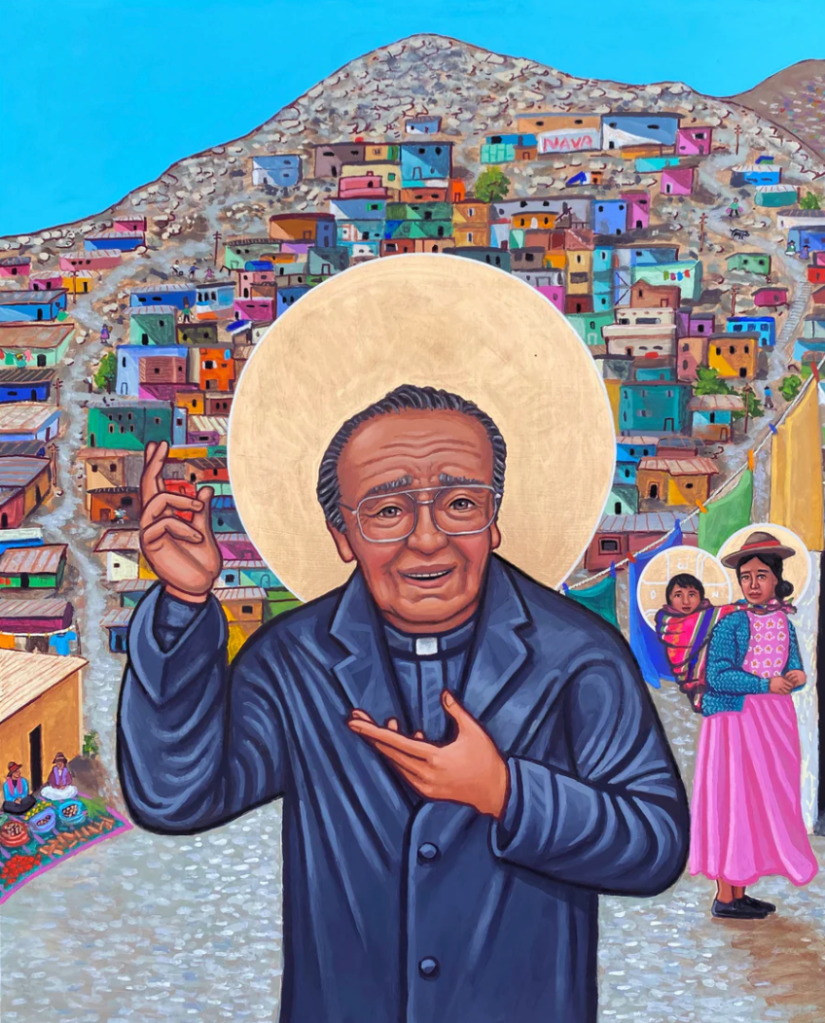

This last Tuesday, our universal church lost a theological giant, Roman Catholic theologian and Dominican priest from Peru named Gustavo Gutiérrez, who passed away at the age of 96. He was known as the “Father of Liberation Theology,” which is a Christian theological tradition that emphasizes social concern for the poor and political liberation for the oppressed. Gutiérrez was born in Lima in 1928 to parents of Hispanic and indigenous descent; and at a young age, he was afflicted with osteomyelitis, an infection of the bones, that made him bedridden, and wheelchair bound for much of his adolescence. While initially studying to become a psychiatrist in Peru, he felt the call to the priesthood and began studying theology in Belgium and France with the leading theologians of his day.[1] Although he could have had a comfortable carer in academia as a professor of theology, he instead chose a life of full-time ministry among the poorest of the poor in Peru, where he realized that much of the theology he had been studying was detached and generally irrelevant to those suffering from extreme poverty. His mostly impoverished parishioners taught him how to practice “hope in the midst of suffering”[2] and he recorded this hard-earned wisdom in a commentary he wrote on the Book of Job, that baffling biblical book about the suffering of an innocent man, a book from which we have been reading for the last several Sundays. Today we read the conclusion of that book; and so, in honor of Father Gustavo, I want to share with you his inspiring interpretation of this book’s dramatic conclusion.

Last Sunday, we read God’s stormy response to Job’s many complaints and then I shared with you Job’s initial response to God. Job said, “I am speechless: what can I say? I put my hand on my mouth. I have said too much already; now I will speak no more.”[3] Job stood in silent awe of God as God spoke to him out of the whirlwind. When Pope Francis spoke of Gutiérrez this week, he described him as “a great man, a man of the church, who knew how to stay silent when he needed to be silent [and] who knew how to suffer when he had to suffer, and who managed to bring forward so much apostolic fruit and such rich theology.” Like Job, Gutiérrez knew when to stay silent. However, after God speaks to Job some more, Job opens his mouth one final time to say the words that we just heard read this morning. Job says, “I had heard of you by the hearing of the ear, but now my eye sees you; therefore, I despise myself, and repent in dust and ashes” (Job 42:6).

Gutiérrez explains that “Job had previously addressed God in protest; [but] now he does so [with] acceptance and [with] a submission that is inspired not by resignation but by contemplative love.”[4] However, when Gutiérrez looks more closely at the original Hebrew, he learns that the final words of Job are poorly translated. What is translated as “I despise myself and repent in dust and ashes” is the Hebrew phrase emsa v’nichamti al-afar va’efer, which is more accurately translated as “I repudiate and change my mind about dust and ashes.” Gutiérrez points out that the phrase “dust and ashes” is an image for groaning and lamentation, so therefore “Job is rejecting the attitude of lamentation that has been his until now…he does not retract or repent of what he has hitherto said, but he now sees clearly that he cannot go on complaining.”[5]

In fact, Gutiérrez commends Job’s honest prayers of lament, explaining that “in [Job’s] lamentation (which is a form of prayer), Job…was close to God, closer than were his friends with their theology.”[6] Job’s “complaints and protests had in fact never outweighed his hope and trust.”[7] Job’s groans and cries of lament were legitimate forms of prayer just as Bartimaeus’s shouting for Jesus in today’s Gospel was a legitimate form of communication. Blind Bartimaeus shouts, “Jesus, Son of David, have mercy on me!” After he was sternly ordered to be quiet, he cried out even more loudly. In the Introduction to his commentary on Job, Father Gustavo writes, “The scorned of this world are those whom the God of love prefers.”[8] In the Bible, Gustavo sees what he calls God’s “preferential option for the poor”[9]; and we see that clearly in our Gospel reading today. While the poor and blind beggar Bartimaeus is scorned by many, Jesus prefers to call for him and then ask him, “What do you want me to do for you?” After Bartimaeus is given what he asks for – his sight—then he stops shouting. If he were to keep shouting after this, then we’d know he’s just shouting for the sake of shouting. Similarly, Job kept complaining even after his unhelpful “comforters” tried to silence him with their victim-blaming theology, but when Job was given an audience with God Himself, he said, “OK. Now I’m done complaining.”

This is an important point because sometimes, in my experience, some people like to complain and for the sake of complaining, even when they are offered or given that which will help them out of their difficult situation. This is not the case for Bartimaeus and Job who both cry out and lament when it is appropriate to do so and who both offer silent praise when it is appropriate to do so.

In the end, Job learns that “God’s love, like all true love, operates in a world not of cause and effect but of freedom and gratuitousness.”[10] According to Father Gustavo, Job learned to leap the fence set up around him “by sclerotic theology which is so dangerously close to idolatry” and he learned to “run free in the field of God’s love.”[11] Gutiérrez concludes his reflections on Job’s conclusion with the prayerful words of a priest named Luis Espinal who was murdered in Bolivia. Espinal prayed, “Train us, Lord, to fling ourselves upon the impossible, for behind the impossible is your grace and your presence; we cannot fall into emptiness. The future is an enigma, our road is covered by mist, but we want to go on giving ourselves, because you continue hoping amid the night and weeping tears through a thousand human eyes.”[12] As we approach a decisive and divisive election, may we remember God’s preferential option for the poor in all we do; and may we trust that, although the future is an enigma, we cannot fall into emptiness. With the promise of God’s grace and presence, we can fling ourselves upon the impossible and, in the words of Father Gustavo Gutiérrez, run free in the field of God’s love. Amen.

[1] Henri de Lubac, Yves Congar, and Marie-Dominique Chenu, to name a few.

[2] https://www.americamagazine.org/faith/2003/02/03/remembering-poor-interview-gustavo-gutierrez

[3] Stephen Mitchell, The Book of Job, 84.

[4] Gustavo Gutiérrez, On Job: God-Talk and the Suffering of the Innocent, 85.

[5] Gustavo Gutiérrez, On Job: God-Talk and the Suffering of the Innocent, 87.

[6] Gustavo Gutiérrez, On Job: God-Talk and the Suffering of the Innocent, 84.

[7] Gustavo Gutiérrez, On Job: God-Talk and the Suffering of the Innocent, 86.

[8] Gustavo Gutiérrez, On Job: God-Talk and the Suffering of the Innocent, xii.

[9] In his lament, Job learned that “his situation was not exceptional but was shared by the poor of this world. This new awareness in turn showed him that solidarity with the poor was required by his faith in a God who has a special love for the disinherited, the exploited of human history. This preferential love is the basis for what I have been calling the prophetic way of speaking about God.” Gustavo Gutiérrez, On Job: God-Talk and the Suffering of the Innocent, 88.

[10] Gustavo Gutiérrez, On Job: God-Talk and the Suffering of the Innocent, 87.

[11] Gustavo Gutiérrez, On Job: God-Talk and the Suffering of the Innocent, 88.

[12] Gustavo Gutiérrez, On Job: God-Talk and the Suffering of the Innocent, 91-92.