Readings for the Feast of the Christ Mass

This sermon was preached at Christ Episcopal Church Eureka for the Christmas Eve service on Saturday December 24, 2023.

Merry Christmas! Some authors have argued that the spiritual character and contribution of each Christian denomination can be represented well with a great feast day of the church, claiming that Easter represents the character of Eastern Orthodoxy, Good Friday the Roman Catholic Church, Pentecost Pentecostalism, and Christmas… Anglicanism, the global Anglican communion of which we Episcopalians are key members.[1] I love this because, although as a priest, I’m supposed to love Easter the most (which is the Great Feast of the Resurrection that gives Christmas its meaning in the first place), I must admit that Christmas is my favorite; and the Anglican-Episcopal Church has made me love Christmas even more. It was, after all, an Anglican author, Charles Dickens, who rescued this holiday from the puritanical clutches of the English pilgrims who first arrived in our country and who despised Christmas with Scrooge-like austerity. Historians generally hold Dickens and his Christmas Carol responsible for making Christmas into the worldwide jamboree that it is today.[2]

One of the ways that the Anglican Church has deepened my love for Christmas is by introducing me to a beloved tradition that I did not practice growing up but have come to treasure in my adulthood: the singing of Silent Night in a candlelit church, after receiving Eucharist and basking in its glow. Although we Anglicans (who are responsible for writing classic carols like “Hark the Herald Angels Sing”[3] and “O Little Town of Bethlehem”[4]) cannot take credit for writing “Silent Night,” which was written by an Austrian Catholic priest named Joseph Mohr, we can take credit for translating the original version of “Silent Night” into the English version we sing today.[5]

This song, which some consider the most popular Christmas carol of all, invites us to reflect on the “heavenly peace” in which the holy infant sleeps, that heavenly peace which the holy infant embodies, that heavenly peace which the holy infant inspires the angelic host to proclaim, when they sing, “Glory to God in the highest heaven, and on earth peace among those whom he favors!” (Luke 2:14), the heavenly peace promised by the prophet Isaiah who called the holy infant the “Prince of Peace” (Isaiah 9:6).

This holy infant was born in Bethlehem, a city that has now cancelled all public Christmas services because today there is no peace in the land. It is indeed a silent night on the streets of Bethlehem tonight, where they usually host joyful celebrations, marching bands, and other festivities around a giant Christmas tree for the locals as well as for the thousands of Christian pilgrims who visit each year. The services have been cancelled in a show of solidarity with the people of Gaza.[6]

As we gather tonight and sing of heavenly peace, wars continue to rage in Ukraine, Sudan, the Holy Land, and beyond. This painful reality reminds me of the challenging words written in an American magazine (The New Republic) back in December 1914 during World War I, “The stench of battle should rise above the churches where they preach [peace and] good-will. A few carols, a little incense and some tinsel will heal no wounds. A wartime Christmas would be a festival so empty that it jeers at us.”[7]

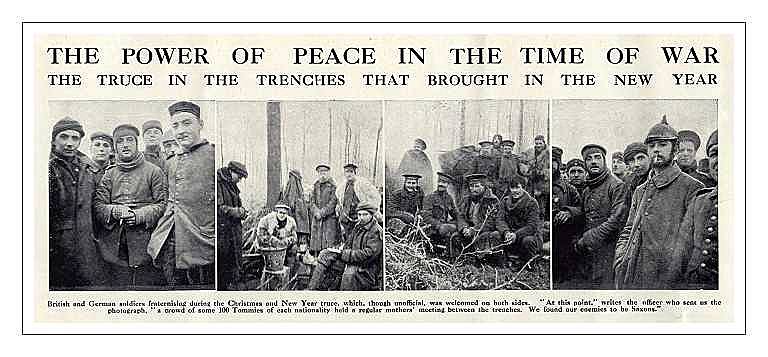

These scathing words were written just days before Christmas Eve, when WWI soldiers in the trenches on both sides of the Western front heard each other singing “Silent Night” and allowed the spirit of that song to overcome them. Private Frank Sumpter of the Allied Forces said, “We heard the Germans singing, ‘Silent Night, Holy Night.’ Our boys said, ‘Let’s join in.’ So, we joined in with the song.” They then shouted “Merry Christmas” to each other between the trenches, aware that their enemy’s experience of the war was just as miserable as their own. Then, according to Private Leslie Walkington, “the British troops began to pop their heads over the side and then jumped down quickly in case [the Germans] shot, but they didn’t shoot. And then,” he says, “we saw a German standing up, waving his arms, and we didn’t shoot.” So, both sides cautiously and vulnerably emerged from the trenches, unarmed, to eventually shake each other’s hands across no-man’s land, where they then exchanged chocolate and cigarettes, buried their dead, and even played football together, all because someone started singing “Silent Night,” the song that invites us to reflect and rest in God’s heavenly peace.

Although the Christmas truce of WWI did not bring an end to the Great War, which lasted another four years, the truce nonetheless remains a powerful sign and foretaste of the promised heavenly peace we proclaim and sing about tonight. This festival is not empty at all, and it does not jeer at us. In fact, the light of this festival shines even brighter amidst the darkness as we hold to the promise of God’s heavenly peace, a peace which we are invited to help bring about.

The holy infant of “Silent Night” is the embodiment of God’s vulnerability. God entered our violent world unarmed to offer us all peace and goodwill. When the vulnerable baby boy grew up, he devoted his life to caring for the weak and the oppressed and teaching others about peace, compassion, and kindness; and he was eventually killed by the soldiers of a violent political empire. After his miraculous resurrection, his followers began to understand his life and death as a gift and gateway for our transformation and liberation and enlightenment and peace. His followers began to understand him not as only the embodiment of God’s vulnerability, but also as the embodiment of God’s promise of everlasting peace and love and life. By receiving this promise and gift so freely given, we become empowered to participate with God in making God’s dream of peace a reality, through our own vulnerable humanity.

As we uphold the beautiful Anglican tradition of singing in a candlelit sanctuary the beloved song “Silent Night” written by an Austrian and translated by an Episcopal priest, I invite us to not only count our blessings as we rest in the heavenly peace of this most holy night, but to also hold in our hearts all those whose lives are ravaged by war and bereft of peace; and to reflect on ways that we might emulate the courageous vulnerability of the Christmas truce soldiers of WWI as well as the vulnerability of Christ, whose heavenly peace will ultimately have the last word. Amen.

[1] Norwegian theologian and church historian Einar Molland (1908–1976) “attempted to describe Christian communions in terms of one special liturgical day. He associates Eastern Orthodoxy with Easter, Lutheranism with Good Friday and Anglicanism with Christmas. The doctrine of the Incarnation has dominated Anglicanism to a remarkable degree. The Puritans of New England were extraordinarily perceptive of how to be most ‘un-Anglican’ by outlawing the celebration of Christmas. The centrality of the Incarnation can be felt in Bishop Andrewes’ sermons on the nativity, studied as a central theme in Hooker, Maurice, and Temple, and sung in the carol ‘O Little Town of Bethlehem’ by Phillips Brooks. Temple’s title for his chief theological work, Christus Veritas, confirms this continuing trend as does the much more recent book, The Human Face of God, by Bishop [John] Robinson.” William J. Wolf, The Spirit of Anglicanism (Wilton CT: Morehouse-Barlow, 1979), 178. We see this Anglican emphasis on the Incarnation also in the sensual poetry of John Donne, George Herbert and Thomas Traherne.

[2] https://www.historyextra.com/period/victorian/charles-dickens-dickensian-christmas-carol-scrooge/

[3] Written by Charles Wesley, who said, “Whatever the world may say of me, I have lived, and I die, a member of the Church of England.”

[4] Written by Phillips Brooks, rector of Trinity Episcopal Church Copley Square Boston and later bishop of Massachusetts.

[5] “It was the Reverend John Freeman Young, of Trinity Church on Wall Street in New York City, who took up the translation of ‘Stille Nacht, Heilige Nacht’ into English. Trinity Church, in lower Manhattan, is a historic parish church, perhaps the most historic in the still-young American colonies, famous for its influential location on Wall Street as well as for the immensity of its financial endowment. Both location and revenue for the church can be traced back to the late seventeenth century, nearly a century before the United States of America separated from the British Empire, when Trinity received its original charter and land from King William III of England. That land, which was then full of cows, quickly became lower Manhattan!” Peter Celano, Twelve Days of Silent Night: The Story Behind the Most Popular Christmas Carol, the Birth of Christ, and What It Means for Our Lives (Brewster MA: Paraclete Press, 2019), 10 – 11.

[6] One Lutheran pastor in Bethlehem, whose church created a manger scene in which baby Jesus lies in rubble instead of a crib, says, “If Jesus were born today, he would be born in Gaza under the rubble. We see the picture of Jesus in every child under the rubble in Gaza. So, this is a letter of solidarity with our people in Gaza, an expression of the meaning of Christmas: God is with the suffering and the oppressed.” https://www.cnn.com/videos/world/2023/12/22/church-leaders-bethlehem-christmas-gaza-cnni-intl-vpx.cnn

[7] Stanley Weintraub, Silent Night: The Story of the World War I Christmas Truce (New York: The Free Press, 2001). xvi.