Readings for the Nineteenth Sunday after Pentecost (Year A) Proper 22 – Track 2

This sermon was preached at Christ Episcopal Church in Eureka CA on Sunday October 8, 2023.

This morning’s sermon is about the reality of war, a call to humility, and the power of poetry or perhaps more simply it’s a call to a courageous and kenotic humility in the face of war. As I shared last Sunday, Paul’s letter to the Philippians can be understood as a long commentary on an ancient Christian poem known as the Christ Hymn or the Kenosis Hymn (Phil 2:6 – 11), which describes Christ as emptying himself to become a humble servant, even to the point of death on a cross. In our reading today, Paul explains how he himself has practiced “kenosis” (self-emptying humility) in his own life by dismissing all his religious accomplishments and credentials and bona fides as “rubbish” (Phil 3:8). The original Greek word here for “rubbish” is skubala (from skubalon), which literally means excrement or feces. Some biblical scholars suggest that it’s equivalent to a four-letter word that I will not utter from this august pulpit, but I imagine I’ve gotten your attention. This would be like me referring to my certificate of ordination and my doctoral diploma as “rubbish,” which they can essentially become if I use them as props to lift myself up and elevate my status rather than as evidence of my training and education to serve the Body of Christ. Paul is trying to empty himself of everything that might prevent him from emulating Chris’s humble and kenotic servanthood so that he too might share in the glory of the Resurrection. This message of kenosis was pertinent to the followers of the Jesus Movement in Philippi, which was previously a small and insignificant farming town in Macedonia until the year 42 BC when a consequential battle was fought between the armies of Octavian and Marc Antony on one side and the armies of Brutus and Cassius on the other. After Octavian’s side won the Battle of Philippi, he became Octavian Augustus the emperor of Rome; and to celebrate his victory, Augustus elevated the town of Philippi to become a prestigious Roman colony, which attracted many retired army veterans and others who were fiercely loyal to Rome and enjoyed the many social benefits of that loyalty. The people of Philippi took special pride in their Roman identity and citizenship while often looking down upon non-citizens. Although the Jesus followers in Philippi were growing in maturity, this cultural pattern of arrogance had begun seeping into their spiritual lives and Paul was concerned, which is why the poem of Christ’s kenotic humility serves as the letter’s center of gravity. Paul calls his readers to practice kenotic humility in a world torn apart by arrogance and war.

I want to offer a story that illustrates this kenotic and courageous humility in the face of war. Since today is just four days after his feast day, you might think I’d talk about that most beloved Italian saint who is also considered the first Italian poet. The name he was given at birth was Giovanni di Pietro di Bernardone, but because he apparently loved French poetry so much that he was given the name “Francis.” You might think I’d talk about his courageous and kenotic humility during the Fifth Crusade when he crossed enemy lines weaponless to speak with the sultan of Egypt about the life-giving kenosis of Jesus Christ. The sultan was impressed with Francis; and some say that he secretly converted and accepted a death-bed baptism. That would’ve been a good story and a good sermon. But instead, I want to share a story that might be even more pertinent to our current times. It’s the story of another poet who embodied kenotic humility in the face of war.

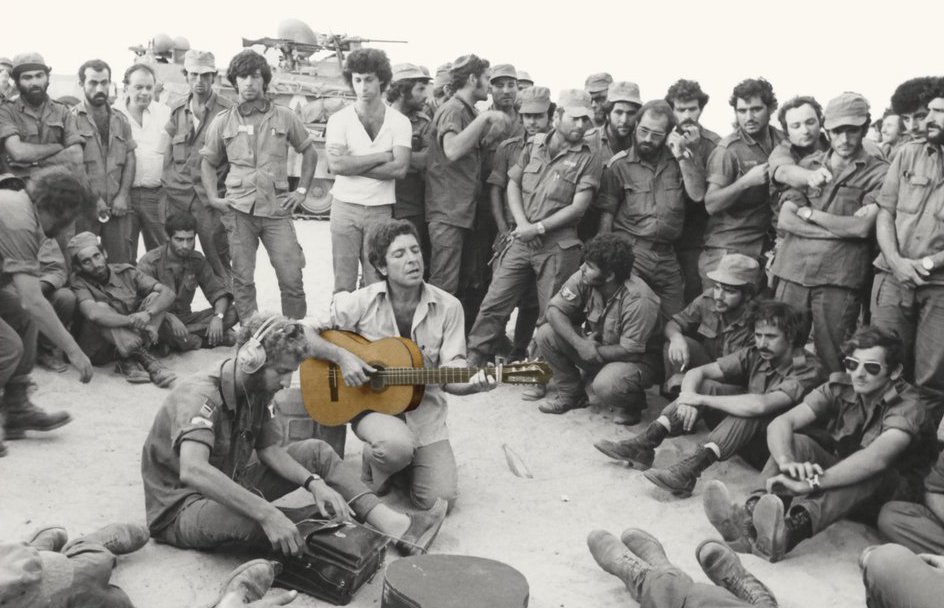

It’s the story of a Jewish poet and musician who traveled to Israel during the Yom Kippur War in 1973. He was about my age at the time, and he hoped to volunteer on a kibbutz to help with food distribution and to replace workers who were called to the front line. However, he was quickly recognized and was asked to play for the troops since this Jewish poet was Leonard Cohen. Although he was initially reluctant to perform, explaining that his songs were too melancholy, and they would just get the soldiers depressed, he ended up going to the frontlines with his guitar and performing regularly for the troops.[1]

Today Cohen’s songs are translated and performed more than any other foreign artist in Israel, but even back in 1973, he was considered a high-caliber celebrity, so people expected that he would request some special treatment, which he never did. Even when offered a real bed, he declined, preferring to sleep on the floor and eat the combat rations just like everyone else.[2] Cohen seemed to consider his celebrity status as “rubbish” if it didn’t help him be somehow useful during a time of crisis. Another performer, who later became an ultra-orthodox rabbi, said that Cohen at the time gave off “an aura of good heartedness, of unusual humanity” and humility.[3]

As a poet, Cohen tried to offer words that might help the troops, who were apparently devouring copies of the Psalms being distributed by the chaplains.[4] In a song titled “Lover Lover Lover” he wrote and sang,

I went down to the desert

To help my brothers fight

I knew that they weren’t wrong

I knew that they weren’t right

But bones must stand up straight and walk

And blood must move around

And men go making ugly lines

Across the holy ground

He later omitted this verse from the song. We don’t know why but we do know that after seeing the war and its effects directly, Cohen began to understand “the difficulty, perhaps even the impossibility, of describing it in a poem or song.”[5] Yet at the same time, he knew the healing power of poetry and song, which, to paraphrase T. S. Eliot, have the power to communicate even before they are understood.

Another songwriter named Matti Caspi who performed with Cohen thought the only honest response to a war is to say nothing. Caspi wrote a song that the troops especially loved to sing which included the lyrics “We have no words / And we have no tune / That’s okay, we can always just sing ‘la la la.’”[6] Later, Cohen would riff on this insight in his live performance of his own poem titled “Tower of Song,” which includes background female vocalists singing “do dum dum dum da do dum dum.” Towards the end of the song, as the female vocalists continue singing, he would say, “I’m so grateful to you, because tonight it’s become clear to me. Tonight the great mysteries have unraveled. And I’ve penetrated to the very core of things. And I have stumbled on the answer. And I am not the sort of chap that would keep this to himself. Do you want to hear the answer? Are you truly hungry for the answer? Then you’re just the people I want to tell it to. Because it’s a rare thing to come up on this. I’m gonna let you in on it now. The answer to the mysteries…Do dum dum dum da do dum dum.”[7]

In a way, he was right because, after all, what is more kenotic than a poet emptying himself of words? And it was through this kenosis, this self-emptying that Cohen discovered his identity as a priest, which is what Cohen means in Hebrew. At his final concert in Israel in 2009, he concluded his performance by lifting his hands and parting his fingers in this priestly formation to bless the people in ancient Hebrew: Yevarekhekha Adonai veyishmerekha.

These illustrations invite us to reflect and ask, ‘How are we being called to practice kenosis (self-emptying humility) in our lives, like Christ, like St. Paul, like St. Francis, and even like Leonard Cohen, amidst devastating wars in Ukraine and now Israel’? What are we willing to relinquish as rubbish so that we might offer authentic service and heavenly benediction to others and somehow help steer the world away from destructive violence and towards what Paul calls “the prize of the heavenly call of God in Christ Jesus”?

[1] Cohen said, “Look, my songs are melancholy, ‘Bird on the Wire’ and so forth, I’ll just get them depressed.” Matti Friedman, Who By Fire: Leonard Cohen in the Sinai (New York: Spiegel & Grau, 2022), 59.

[2] Matti Friedman, Who By Fire: Leonard Cohen in the Sinai (New York: Spiegel & Grau, 2022), 92.

[3] Pupik Aaron, a comic actor and occasional singer whose real name was Mordechai. Friedman, Who By Fire, 59, 92.

[4] Friedman, Who By Fire, 125.

[5] Friedman, Who By Fire, 105.

[6] Friedman, Who By Fire, 95.

[7] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nceRfJJZcP4, accessed October 2023.

Works Referenced and Consulted: