This paper was presented at the College of St. John the Evangelist in Auckland New Zealand as part of the Te Piri Poho Research Seminar on August 17, 2023.

On the island of Iona in the Scottish Hebrides, there is a well of St. Brigid which is considered the last remaining well of its kind in all of Scotland. Located on the top of the island’s highest hill called Dùn-Ì, it is a little pool of water cuddled beside a cliff, fed by a subterranean spring that flows from a deep opening within the rock. Pilgrims are invited to approach the pool and form their own fleshy makeshift chalice by cupping their hands together and submerging them under water.[1] They are then invited to lift their cupped hands out of the pool and bring the water not only up to their mouths to taste it, but also to their ears and eyes and nose so that the holy waters of St. Brigid bless all their senses.

When I participated in this ritual under the guidance of Celtic spirituality teacher and author John Philip Newell, I recalled the invitations within John’s Gospel to appreciate our five senses and to experience God’s blessings through them.[2] Before cupping my hands together, I used them to stir the waters and then to notice my own reflection in the pool after the waters settled. I then rolled up my sleeves and brought up a hand-cupful of water to my ears, appreciating my sense of hearing as I listened to the wind and remembered Jesus’s invitations to Nicodemus to reflect upon the wind’s unpredictable movements.[3]

As I anointed my eyes with the well water, I appreciated the gift of vision, noticing the viridescent gleam of the grass, the textures of the crystal-granite rock, and the colorful beauty of my fellow pilgrims. I even began to appreciate the mud caked along the borders of Brigid’s well, which has such a natural quality to it that one local resident referred to it jokingly as a “puddle.” The mud reminded me of the ointment that Jesus made from his own saliva to anoint the eyes of the man born blind, who was able to see only after experiencing what it is like to be seenby Jesus. I felt grateful for the experience of being known and seen by the pilgrimage guide and my fellow pilgrims, who like me were looking at much more than a mere puddle. We were basking in the glory of what has been called St. Brigid’s “Fount of Eternal Youth.”

Although the well resides within the pasture lands of island sheep, I was assured that the water was safe for humans to drink. In fact, when we interrogated our leader with a strong dose of skepticism about the well’s promise of “eternal youth,” he told us wryly that he drinks from it at least once a year and that he’s 107 years old. Smiling, I decided to fill my hand chalice and bring the water to my lips. As the naturally cool liquid refreshed my mouth and belly, I recalled the words that Jesus shared with the Samaritan woman at the well: “the water I offer you will become within you a spring of water gushing up to eternal life” (John 4:14). As I drank the water, I could not help but breathe in its earthy aroma through my nose, which I also anointed with the well’s water. I then noticed how all the fragrances of the island – the sheep, the shores, the moors, and the hairy coo—filled my senses much like the way the fragrance of Mary’s pure nard filled up the house in the twelfth chapter of John.

Finally, I attended to my sense of touch by noticing how the water felt when I let my hands hover just centimeters above it and then slowly descend into its liquid body. After some more stirring and splashing, I brought my drenched hands to my chest to let the well bless my heart. While holding my hand to my heart, I noticed for the first time, as if St. Brigid was waiting to reveal it to me, the heart-shaped contour of the pool. This heart-to-heart connection with the well helped me tap into the expansive power of the heart sense, through which I could begin to imagine and feel what the water felt. It was this sixth sense, the heart sense, that reminded me of the author of John’s Gospel, the beloved disciple who reclined upon the bosom of Jesus (13:23), where, according to the Celtic Christians, he listened to the heartbeat of his rabbi.

As I read the Fourth Gospel, I continually encounter its invitations to let the life-giving power of Christ wash over me and my senses the way the waters of St. Brigid’s Well did. I see how the Gospel invites us to value our own human flesh and to listen to the heartbeat of God pulsating within the earth and within ourselves. I have learned that by highlighting these sensual invitations in John, I stand within a stream of particularly Anglican, English, and Celtic Johannine thought. In this paper, I will offer a highly selective and far-from-comprehensive reception history of John’s Gospel among Celtic Christians, medieval English authors, and modern Anglican scholars, attending particularly to the stream of thought that highlights the Fourth Gospel’s invitations to appreciate our senses and to connect with the earth, the body, and the elements. This stream, which was shaped by the indigenous Celtic people’s fruitful engagement with the Gospel of John, is one that can still offer helpful and refreshing wisdom for Anglicans and indigenous communities today. It seems only appropriate for me to offer this paper at an Anglican theological college, founded on an island of indigenous tribes, and named after the traditional author of the sensual Gospel, St. John the Evangelist, Hato Hone.[4]

The Celtic Spiritual Father: Listening to the Heartbeat of the Divine

Scholars have recognized significant links between Celtic spirituality and the spiritualities of tribal indigenous peoples around the world, especially regarding prayers and practices that help bind the people to the earth, the body, and the elements.[5] Celtic spirituality author Esther de Waal writes,

Sharing Celtic litanies, creation celebrations, domestic prayers or protection blessings with Native American peoples in Oregon, with black South Africans in Johannesburg, or with ordinands’ wives in Tanzania…has been an extraordinary personal experience, for their immediate reaction has been that this speaks to them of what they instinctively know, and they feel themselves totally at home, finding much that is already familiar in their own tradition.[6]

In my own experience of teaching Celtic Spirituality to seminary students, I was pleased and yet not entirely surprised to learn that a Navajo student felt particularly at home in praying the Lorica or Breastplate Prayer of St. Patrick, which calls for a connection to the wind, the sea, the fire, and the rocks and for protection over the body.[7] In his book The Conversion of the Māori, historian Timothy Yates compares the Māori understanding of the Bible to the Celtic Christian understanding of the cross, which were both perceived as tools for protection of the body against evil spiritual forces.[8] Indigenous communities seem to resonate with prayers and practices that affirm and protect the body. The indigenous Celtic communities found such a strong resonance with the author of the flesh-affirming Gospel of John that they claimed the Evangelist to be the source of some of their most important practices, particularly their dating for the celebration of Easter as well as the style in which Celtic bodies cut their hair.[9] Both practices aroused conflict with the Roman church and subsequently led to the Synod of Whitby in 664 when King Oswiu of Northumbria had to decide which tradition he was going to endorse: the Roman or the Celtic tradition. To use Archbishop Don Tamihere’s categories, this Synold can be understood as a debate between the colonial (Roman) and the indigenous (Celtic) minds.[10] When Bishop Colman of Lindisfarne argued in favor of the Celtic practices, he appealed to the authority of St. John, from whom both their dating of Easter and their style of tonsure had apparently derived. Bishop Colman explained,

The blessed evangelist John, the disciple whom the Lord specially loved, is said to have celebrated Easter this way…I’m surprised that you are willing to call our efforts foolish, seeing that we follow the example of that apostle who was reckoned worthy to recline on the breast of the Lord; for all the world acknowledges his great wisdom.[11]

Although his opponent Bishop Wilfrid of York convinced King Oswiu to endorse the Roman way of dating Easter as well as the Roman tonsure, Colman’s argument solidified the link between Celtic spirituality and Johannine spirituality. In his book Listening for the Heartbeat of God, John Philip Newell sees both spiritualities as earth-affirming and flesh-affirming in contrast to Roman Catholic spiritualities that developed primarily out of the Synoptic Gospels, especially Matthew. Though the dichotomy that Newell sets up between Celtic / Johannine spirituality and Roman / Matthean spirituality might be over-simplified, he offers an informative contrast, especially when he writes,

In John’s Gospel, Mary, takes a pound of costly perfume, anoints Jesus’ feet and wipes them with her hair. “The house,” says John, “was filled with the fragrance of the perfume” (John 12:3). In Matthew’s version, on the other hand, an unnamed woman is described simply as coming to Jesus and pouring oil on his head as he sits at table (Matthew 26:7)…In John’s Gospel there is a readiness to delight in the sensory and in the closeness of affection. Matthew is more cautious. John’s spirituality accentuates…the body [which] is regarded as good and intimacy becomes an expression of God’s love.[12]

Since the Celtic Christians understood the author of John’s Gospel to be their spiritual progenitor, we may imagine that John, in its affirmation of the flesh, played an important role in facilitating the growth and flourishing of Christianity among the indigenous Celtic communities.

In the ninth century, the brilliant pan-entheist Celtic theologian John Scotus Eriugena (815 – 877) wrote a homily on the Johannine prologue, which translator Christopher Bamford calls “The Heart of Celtic Christianity.”[13] Inspired by the traditional understanding of the fourth evangelist as the eagle,[14] John Scotus begins his homily with a reference to the senses, saying, “The voice of the spiritual eagle resounds in the ears of the church. May our external senses grasp its…sounds.”[15] Echoing the Celtic appreciation of John, he describes the evangelist as the blessed theologian to whom has been given[16] the capacity to not only penetrate hidden mysteries but also to reveal them “to the human mind and the senses.”[17] He then returns to that favorite Celtic image of John leaning on the bosom of the Lord, which he understands as a symbol for contemplative prayer. In this contemplation, Eriugena invites us to listen to the heartbeat of God pulsate within our own hearts, sensing that the divine is the ground and source of every beat and breath, throbbing in the heart of all creation. In this contemplation, we learn that God is our being; we are not God’s being, but we participate in God’s being through the grace of our existence; and it is through belief in the One who is divine by nature that we can participate in divinity and in the ultimate restoration of the earth, the cosmos, and all the celestial hierarchies.[18]

The Celtic Christian understanding of John invites us to connect especially with our heart sense and the best way to get in touch with our heart sense is to simply place our hand on our hearts, which I invite you to do now. I invite you to receive each heartbeat as a gift from the divine who infuses all of creation with the gratuitous gift of existence and who invites us to participate in the restoration of all things by abiding in this love.

The English Peoples’ Drinking Buddy: Delighting in the Gift of Taste

Writing a century before John Scotus Eriugena, the monk of Wearmouth-Jarrow known as the Venerable Bede (673 – 735) was determined, before he died, to finish his translation of the Gospel of John.[19] Although the unfinished translation is unfortunately lost, we can still get a sense of Bede’s love for Johannine wisdom from his homilies.[20] Like Eriugena, this Father of English Spirituality honored St. John as a model contemplative in contrast to the more active and reactive St. Peter. However, according to Bede, while leaning on the bosom of Jesus, John was not just listening to the heartbeat of his teacher, he was imbibing heavenly wisdom from Christ’s breast, wisdom which was being poured forth for all of us to receive through him.[21] Although Bede’s imagery might sound extreme to modern readers, the sensuality is undeniable and the particular emphasis on the sense of taste is one that continues to appear throughout medieval English interpretations of the apostle and his Gospel.

The tenth-century English abbot Aelfric of Eynsham (955 – 1012) preached a hagiographical sermon on St. John in which he culls legends from the apocryphal book Acts of John.[22] By recognizing the stories Aelfric chose to highlight, we are given a glimpse of the aspects of John and his Gospel that seemed to resonate most with the English people in the Middle Ages. Aelfric describes John as Christ’s beloved friend and then proceeds to bookend his homily with stories of drinking. The first story recounts Christ’s first miracle in which Jesus miraculously brings more wine to a wedding party. Clearly, the Johannine Jesus delights in earthly pleasures and the English people knew it. However, according to Aelfric’s legend, this miracle inspired the groom of the wedding to abandon his bride and follow Jesus as a lifelong virgin; and the groom was John himself.[23] The English people’s veneration of John’s virginity reminds us of the importance of occasional abstinence and appropriate restraint when it comes to delighting in the body and sensuality.[24]

One of the final stories in Aelfric’s homily takes place during John’s later years when he encounters a pagan priest in Ephesus named Aristodemus, who forces John to drink a fatal poison. Confident that God will protect and sustain him, John agrees to do so and then proceeds to make the sign of the cross over the cup of poison, over his mouth, and over his whole body. He blesses the poison in God’s Name and drinks it all “with a confident spirit.” After watching John closely for three days and seeing that he only displays a “joyous countenance without pallor and fear” the people become convinced that John’s God is indeed the one true God.[25] Although this is not a biblical story about John, it became wildly popular especially among Christian artists of the late Middle Ages and early Renaissance, who frequently portrayed John holding a chalice with a serpent emerging from the cup’s rim, embodying the poison as it slithers away, repelled by the power of John’s cruciform blessing. In both of Aelfric’s stories, potentially hazardous beverages—alcohol and then fatal poison—become a source of joy, friendship, and new life when approached with prayer, restraint, and the life-giving power of Christ.

The 14th century English anchoress and mystic Julian of Norwich (1343 – after 1416) writes explicitly about sensuality and discovers, through her revelations of divine love, that contemplation is a way to unite our “sensuality” with the part of ourselves (which she calls our “substance”) that is already at one with the divine.[26] She also writes about experiencing God in the joy of laughter, in bodily pain and sickness, and even in the wondrous process of human digestion.[27] As an anchoress, Julian was likely familiar with the spirituality expressed in the Guide for Anchoresses, an anonymous medieval English manual that once again links St. John with the senses, especially our sense of taste. In a meditative reflection on the Passion, the author writes,

As [Christ] hung there he could smell the reek [of the dying thieves]…He was also tormented in all his other senses: in his sight when he saw his precious mother’s tears –and St. John the evangelist’s …He tasted gall on his tongue, to teach the anchoress that she should never again grumble about any food or drink, however unappetizing it may be. If she can eat it, eat it and thank God sincerely for it; if she cannot, let her be sorry that she must ask for more delicate food.[28]

According to this medieval spiritual manual, Jesus received the gall on the cross for the purpose of teaching us to appreciate our food and drink, to appreciate our sense of taste! Just as the ancient Celtic reception of John invites us to listen to the heartbeat of Christ in our bodies and in the earth, the medieval English reception of John invites us to appreciate our sense of taste, to delight in food and drink, with gratitude and proper restraint and without grumbling. To drive this point home, I would ideally provide you all with some delicious wine or some other equally attractive beverage and invite us all to make the sign of the cross over the drink, over our mouths, and over our bodies, before delighting together in the gift of taste. Unfortunately, I have not prepared all this so that will have to be your homework.

The Anglican’s “Weakness”

The stream of Johannine thought shaped by ancient Celtic and medieval English spiritualities seems to flow most strongly in the work of several modern Anglican biblical scholars. Soon after deciding to write my dissertation on John, I met a Dominican friar and New Testament scholar (Fr. Benedict Viviano) who, upon learning that I was an Episcopal priest studying the Fourth Gospel, told me that “Anglicans have a weakness for the Gospel of John.” He then proceeded to give me a list of recommended commentaries and articles on John, with the inclusion of the following charge: “As an Anglican you should own and consult the all-holy [Brooke Foss] Westcott; then [John Henry] Bernard, then the ineffable Sir Edwyn Hoskyns.”[29] Although the scholarship of these late 19th– and early 20th-century Anglicans is mostly outdated and did not make an appearance in my dissertation, I decided to follow the Dominican’s advice nonetheless, wondering why Anglicans were so drawn to this particular Gospel.

The early triumvirate of Anglican Johannine scholars to which I was first introduced all affirmed the absolute centrality of the Incarnation of Christ, expressed clearly in that foundational phrase: the Word became flesh (John 1:14). Bishop Westcott, whose books filled the shelves of most Anglican clergy in the late 19th and early 20th century,[30] insisted that every syllable in the Gospel of John was written to reinforce the truth of Christ’s enfleshment.[31]

Bernard highlighted the Gospel’s frequent portrayal of Jesus as a true, flesh-and-blood human, which meant that he was sometimes tired, thirsty, sweaty, tear stained and even emotionally troubled.[32] Hoskyns touched upon the scandal of sensuality within John, explaining that although the idea had flummoxed many spiritual people of ancient times, the divine Christ was not some ghostly and translucent apparition, but was indeed a physically visible, audible, and tangible human being.[33] Also, Hoskyns, with the middle name Clement, challenges the categories of his namesake saint, Clement of Alexandria, who contrasts John’s spiritual Gospel with the Synoptic Gospels that focus on the sensible or bodily facts about Jesus.[34] Insisting that the spiritual can also be sensual, Hoskyns asserts that John’s Gospel is indeed “a ‘bodily’ Gospel.”[35]

The Johannine affirmation that God became enfleshed in Christ clearly seized the attention, admiration, and awe of these Anglican authors and many others followed suit, particularly William Temple,[36] John A. T. Robinson,[37] Barnabas Lindars,[38] and Richard Bauckham.[39] Of course, Anglicans are not the only readers of John who are drawn to the Gospel’s proclamation of the Incarnation and who then underscore it in their scholarship. However, there is something unique about the spiritual magnetism between Anglicans and the Fourth Gospel.[40] Anglicans tend to understand the Christian faith as primarily incarnational. Perhaps Richard Schmidt put it best when he said it is the doctrine of the Incarnation that “vibrates most strongly in the Anglican soul.”[41] Certainly this embrace of the Incarnation had something to do with what my Dominican friend called a “weakness” among Anglicans when it comes to the Fourth Gospel. As I continued to follow this trend among Anglican Johannine scholars, a sense of pride and kinship with my Anglican ancestors began to grow within me as I found myself also succumbing to that same weakness.

An Anglican Johannine Scholar of Oceania

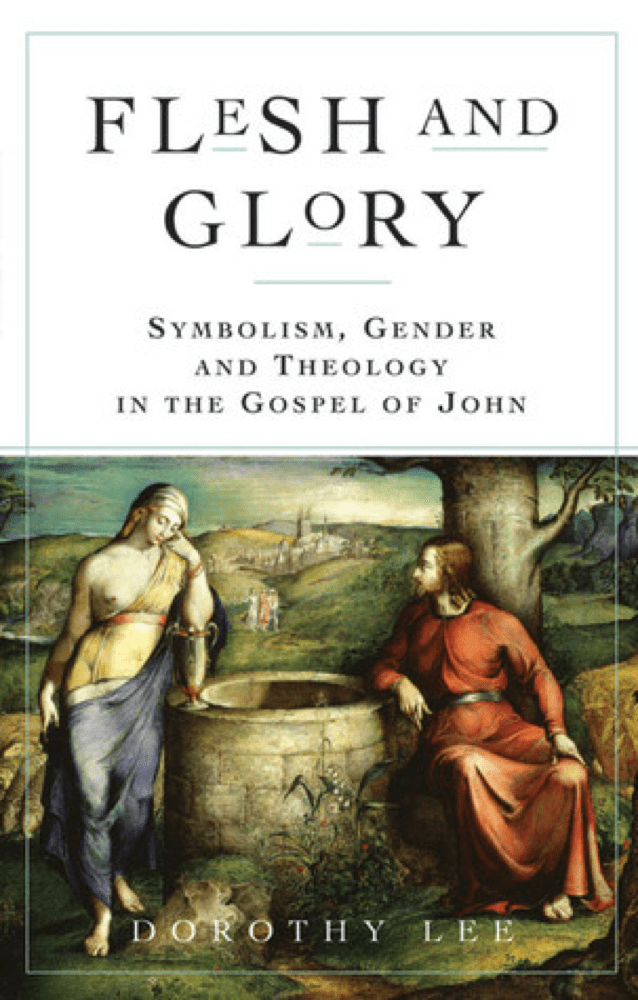

It is the work of an Anglican Johannine scholar of Oceania, whose scholarship most clearly expresses the thematic stream we have been following throughout the ancient Celtic, medieval English, and modern Anglican spiritual traditions. I personally came to understand and appreciate the Fourth Gospel as sensual and flesh-affirming thanks to this Anglican priest and professor, the Rev. Canon Dorothy Lee, who teaches at the University of Melbourne.

In 2010, she published an article titled “The Gospel of John and the Five Senses,” which functioned like magical mud made from Christ’s spittle, opening my eyes to see that to which I was formerly blind: the Fourth Gospel’s frequent emphasis and affirmation of the body and the senses.[42] I had previously experienced the Johannine Jesus as “a detached god who seems to glide across the face of the earth” and an aloof “stranger to the world.”[43] However, thanks to Dorothy Lee, I began to see how much John’s flesh-and-blood Jesus loves the world and delights in earthly pleasures. After all, he inaugurates his ministry by miraculously bringing more wine to a wedding party in which the guests are already sufficiently drunk (2:10); his conversation with the Samaritan woman at the well is charged with nuptial and even erotic overtones (4:1-42); he offends listeners with a description of the Bread of Life that is far too fleshy for their religious tastes (6:60-61); he makes healing ointment out of dirt and saliva (9:6); he receives an expensive and seemingly excessive foot anointing from a female friend (12:1-8); and he himself strips down to almost nothing to wash his disciples’ feet (13:1-11). This Johannine Jesus is no stranger to the world.

According to Lee, the five senses in John operate symbolically to point to deeper spiritual truths and enable us to grasp the “incarnational shape of salvation.”[44] Jesus himself said, “If you do not believe when I talk about earthly things, how can you believe if I talk to you about heavenly things?” (John 3:12). Our experience of God’s glory and our faith in Christ can be enhanced by attending wisely, mindfully, and with gratitude to some of the “earthly things” which the Gospel underscores, specifically the five bodily senses. In her book Flesh and Glory, Lee highlights the fleshly and material realities that function as vehicles for experiencing divine glory and deepening our faith.[45] Building upon her study of the symbolic narratives of the Fourth Gospel, Lee upholds the human flesh as a core symbol, if not the core symbol, in the Fourth Gospel.[46]

Unfortunately, Christianity has been used throughout church history to justify the denigration of the earth and the body. Author Thomas Ryan uses a Johannine metaphor when he says,

[The] biblical legacy is fine wine, but alas, Christianity has poured copious water into its wine and resisted the radical nature of its own good news where the body is concerned. On the one hand, it has the highest theological evaluation of the body among all the religions of the world [thanks to the Gospel of John], and on the other hand, it has given little attention to the body’s role in the spiritual life in positive terms. High theology; low practice.[47]

In John’s Gospel, I see high theology as well as invitations to spiritual practice as it offers several practical ways to deepen our love for these fleshly vehicles of God’s glory. John invites us to listen to the wind, to enjoy the refreshing taste of cold water (or wine!), to go outside and pick up a handful of dirt and observe all the tiniest details the human eye can see, to smell the fresh air in a forest (or on the trails of St. John’s Bush), to massage our feet and wiggle our toes, to place our hand on our heart and to rest and abide in the God who gave us each a body and who became enfleshed in a body so that we may know that God’s gift of creation is not just good, but in the words of Genesis, “very good.”

Conclusion

This stream, which has underscored the importance of the Incarnation, has significant implications for Anglican spirituality. By affirming that creation can teach us about the Creator, “Anglican incarnationalism” has helped inspire British empiricism as well as American pragmatism.[48] This same affirmation has inspired the Anglican tradition’s embrace of beauty and the arts, which are seen less as distractions and more as effective instruments for facilitating worship and devotion. Furthermore, incarnationalism motivates the pursuit of social justice as Anglicans not only perceive humans as made in God’s image but also in affirming the human body as a vehicle for God’s glory and the earth as the place for God’s kingdom to come.[49]

At their best, Anglican missions have been informed, inspired, and driven by an incarnationalism that acknowledges the inherent goodness in other cultures and offers the Gospel as a gift for the preservation, growth, and fulfillment of all human cultures.[50]

Along with inspiring faithful pursuit in the sciences, the arts, social justice, and missions, the incarnationalism expressed in John’s Gospel and underscored throughout the Celtic, English, and Anglican traditions invites us to appreciate, here and now, the gift of our bodies. This Celtic, English, and Anglican reading of John’s Gospel offers us a particularly powerful and biblically rooted set of practices to help us connect to the earth and our own human flesh, through which God chose to make his glory known.

[1] The poi chant in the New Zealand prayer book also uses the image of the hand as cup (te kapu taku ringa). A New Zealand Prayer Book, 154.

[2] Although other human senses have been recognized, such as proprioception (a sense of space), the five senses of audition, taste, vision, olfaction, and touch have been traditionally upheld ever since Aristotle discussed them extensively in his De Anima 2.5 – 12. See Aristotle, On the Soul, translated by W.S. Hett (London: Heinemann, 1957), 94 – 139. In this paper, I will primarily focus on the traditional five senses along with the “heart sense.”

[3] The Hebrew word for wind (ruach)is the same word for “breath” and “spirit.” This multivalent word shares resonances with the Māori word mauri, the breath of life, which is shared between two individuals when they gently press their foreheads and noses together in a greeting known as Hongi.

https://www.otago.ac.nz/maori/world/tikanga/powhiri/index.html, accessed August 16, 2023.

[4] Throughout this paper, I will refer to St. John the Apostle as the author of the Fourth Gospel, using John the Apostle and John the Gospel sometimes interchangeably. Biblical scholars question the traditional assertion that John the Apostle is the author of the Fourth Gospel because the Gospel attributed to him does not include several significant events in the ministry of Jesus to which he, according to the Synoptic tradition, was privy: the raising of Jairus’s daughter, the Transfiguration, and Jesus’s agony in the Garden of Gethsemane. Also, the Fourth Gospel does not include the calling of the sons of Zebedee who left their nets to follow Jesus, an event that we would expect to be included in a Gospel written by one of the sons. Moreover, according to the Synoptic tradition, no disciple was present at the cross (“all of them deserted him and fled” Mark 14:50), yet the “Beloved Disciple”/author stood with the women at the cross. The Gospel’s author never identifies himself (the Beloved Disciple) with John son of Zebedee, even when the “sons of Zebedee” are mentioned in John 21:2. The Gospel’s author is designated within the text as the “Beloved Disciple” and many other candidates for the identity of this Beloved Disciple have been put forth: John Mark, Matthias, the Rich Young Ruler, Paul, Benjamin, John the Elder, Lazarus, Mary Magdalene, and the Samaritan Woman, to name a few. See R. Alan Culpepper, John, Son of Zebedee, 77 – 85. Barring any new evidence, these arguments will remain in the realm of conjecture. However, we do not need to resort to educated guesses when it comes to acknowledging the fact that we have a Gospel that has traditionally been attributed to John the Apostle and has, in fact, been referred to as “The Gospel of John” for the vast majority of church history. As an Episcopal priest within the Anglican tradition, I’m personally inclined to locate myself within a stream of Anglican Johannine thought, which includes the classic work of B.F. Westcott who argued “that the fourth Gospel was written by a Palestinian Jew, by an eyewitness, by the disciple whom Jesus loved, [and therefore most likely] by John the son of Zebedee.” Brooke Foss Westcott, The Gospel According to St. John: The Greek Text with Introduction and Notes, Vol 1 (London: John Murray, 1908), lii. So instead of throwing our hands up and saying, “We can never know!” when it comes to the historical authorship and potentially redacted composition of John’s Gospel, I suggest we acknowledge and claim the text and traditions that we do indeed have available to us and try to glean from them some wisdom that might encourage us, refresh us, and help us to draw closer to the Word made flesh.

[5] I was pleased to see a “Cross from Iona” on display at the John Kinder Theological Library, as part of the Alison Ballantyne collection.

[6] Esther de Waal, “Celtic spirituality: a contribution to the worldwide Anglican Communion?” in Anglicanism: A Global Communion, edited by Andrew Wingate (New York: Church Publishing Inc, 2000), 52

[7] “Patrick’s Breastplate” in Celtic Spirituality, translated and introduced by Oliver Davies, (Mahwah NJ: Paulist Press, 1999), 118. The student who resonated deeply with the prayer was the Rev. Cathlena Plummer, daughter of the Right Reverend Steven Tsosie Plummer, former bishop of Navajoland and the first Navajo bishop of the Episcopal Church. I appreciate the fact “St. Patrick’s Breastplate” is included in A New Zealand Prayer Book: He Karakia Mihinare o Aotearoa (Auckland NZ: William Collins, 1989), 158 – 159.

[8] Timothy Yates, The Conversion of the Māori: Years of Religious and Social Change, 1814 – 1842 (Grand Rapids MI: William B. Eerdmans, 2013),69 – 70. The Māori referred to the Bible as a gun (pu) to protect them from the evil spirit, Hiro.

[9] Unlike the Roman monastic tonsure which left a narrow fringe of hair around the back and brow of the head, the Celtic monastic tonsure left hair only on the backside of the head, a style that Celtic Christians claimed to have adopted from St. John himself. Clinton Albertson, S.J. Anglo-Saxon Saints and Heroes (Bronx NY: Fordham University Press, 1967),42 n. 17, as cited in R. Alan Culpepper, John, the Son of Zebedee: The Life of a Legend (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1994), 277.

[10] Archbishop Don Tamihere’s sermon at the Pōwhiri and Eucharist for the Installation and welcoming of Dr. Emily Colgan, the Manukura of The College of St. John the Evangelist. Thursday, 10 August 2023.

[11] Bede, Ecclesiastical History 3.25. According to the Life of Bishop Wilfrid, Bishop Colman said, “Our fathers and predecessors, plainly inspired by the Holy Spirit as was Columba, ordained the celebration of Easter on the fourteenth day of the moon, if it was a Sunday, following the example of the Apostle and Evangelist John ‘who leaned on the breast of the Lord at supper’ and was called the friend of the Lord. He celebrated Easter on the fourteenth day of the moon and we, like his disciples Polycarp and others, celebrate it on his authority…” Life of Bishop Wilfrid, chap. 10, trans. Bertram Colgrave, The Life of Bishop of Wilfrid by Eddius Stephanus (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1927), 21.

[12] John Philip Newell, Listening for the Heartbeat of God: A Celtic Spirituality (Mahwah NJ: Paulist Press, 1997),101 – 102. Also, see Dominika A. Kurek- Chomycz, “The Fragrance of Her Perfume: The Significance of Sense Imagery in John’s Account of the Anointing in Bethany” Novum Testamentum 2010, Vol 52, Fasc. 4 (2010), 334 – 354.

[13] John Scotus Eriugena, The Voice of the Eagle: The Heart of Celtic Christianity: Homily on the Prologue to the Gospel of John, translated by Christopher Bamford (Hudson NY: Lindisfarne Press, 1990).

[14] The symbols of the four evangelists are associated with the four living creatures described in Ezekiel 1: 5 – 10 and Revelation 4:6 – 8. The man/angel represents St. Matthew, the lion St. Mark, the ox St. Luke, and the eagle St. John. Irenaeus, who was a student of Polycarp, who was believed to be a student of John the Apostle, was the first to correlate the four living creatures with the four evangelists; however, he connected St. John with the lion and St. Mark with the eagle (Adversus Haeresus 3.11.8). Jerome’s correlations became the most dominant (Commentary on Matthew Preface 3).

[15] John Scotus Eriugena,“Homily on the Prologue to The Gospel of John” in Celtic Spirituality, Oliver Davies (Mahwah NJ: Paulist Press, 1999), 411.

[16] John Scotus explains that the Hebrew name John when translated into Greek means “to whom is given.”

John Scotus Eriugena, The Voice of the Eagle: The Heart of Celtic Christianity: Homily on the Prologue to the Gospel of John, translated by Christopher Bamford (Hudson NY: Lindisfarne Press, 1990), 22.

[17] John Scotus Eriugena, The Voice of the Eagle, 22.

[18] For Eriugena, this final restoration, or apokatastasis, includes the restoration of fallen angels, even the devil himself.

[19] According to Cuthbert, Bede had translated 1:1 to 6:9b of John’s Gospel before passing away: “During those days there were two pieces of work worthy of record…which he desired to finish: the gospel of St. John, which he was turning into our mother tongue to the great profit of the Church, from the beginning as far as the words, ‘But what are they among so many?’ [John 6:9b] and a selection from Bishop Isidore’s book…” Cuthbert’s Letter.

[20] Perhaps the most famous painting of Bede is the Irish painter J. D. Penrose’s imaginative portrayal of the author dictating his translation of John’s Gospel while sitting on his deathbed.

[21] The Venerable Bede, Homily on St. John 1.9, Corpus Christianorum Series Latina 112:60, 3; translated by Martin and Hurst CS 110, p. 88 and n. 8, as cited in Susan Cremin, “St. John and the bosom of the Lord in Patristic and Insular tradition” in The Beauty of God’s Presence in the Fathers of the Church: The Proceedings of the Eighth International Patristic Conference, Maynooth, 2012, ed. Janet Elaine Rutherford (Portland OR: Four Courts Press, 2014), 188. The idea of St. John imbibing wisdom from the breast of Christ first appears in the writings of St. Augustine who said, “For this beginning of the Gospel St. John poured forth for that he drank it in from the Lord’s Breast. For you remember, that it has been very lately read to you, how that this St. John the Evangelist lay in the Lord’s bosom. And wishing to explain this clearly, he says, On the Lord’s breast;

that we might understand what he meant, by in the Lord’s bosom.

For what, think we, did he drink in who was lying on the Lord’s breast? Nay, let us not think, but drink; for we too have just now heard what we may drink in.” St. Augustine, “Sermon 69 on the New Testament,” translated by R. G. MacMullen, from Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, First Series, Vol 6, edited by Philip Schaff (Buffalo NY: Christian Literature Publishing, 1888). Revised and edited for New Advent by Kevin Knight. http://www.newadvent.org/fathers/160369.htm

[22] Aelfric, “St. John the Apostle” in Anglo-Saxon Spirituality: Selected Writings, translated by Robert Boenig (Mahwah NJ: Paulist Press, 2000),100 – 108.

[23] Those who might feel sympathy for the bride in this situation, abandoned by her groom, might be relieved to learn that later legends understood the bride to be St. Mary Magdalene, who became just as close—if not closer—of a disciple of Christ.

[24] Aelfric, “St. John the Apostle” in Anglo-Saxon Spirituality,100.

[25] Aelfric, “St. John the Apostle” in Anglo-Saxon Spirituality,106 – 107.

[26] Daniel London, “‘Pray Interly’: Julian of Norwich’s Spirituality of Prayer” in Compass: A Review of Topical Theology (Vol 49: No. 3 Spring 2015), 19 – 20.

[27] Julian of Norwich, Showings, trans. Edmund Colledge and James Walsh (Mahwah NJ: Paulist Press, 1978).

[28] Anchoritic Spirituality: Ancrene Wisse and Associated Works, translated by Anne Savage and Nicholas Watson (Mahwah NJ: Paulist Press, 1991), 87.

[29] Email from Benedict Viviano sent on December 30, 2012.

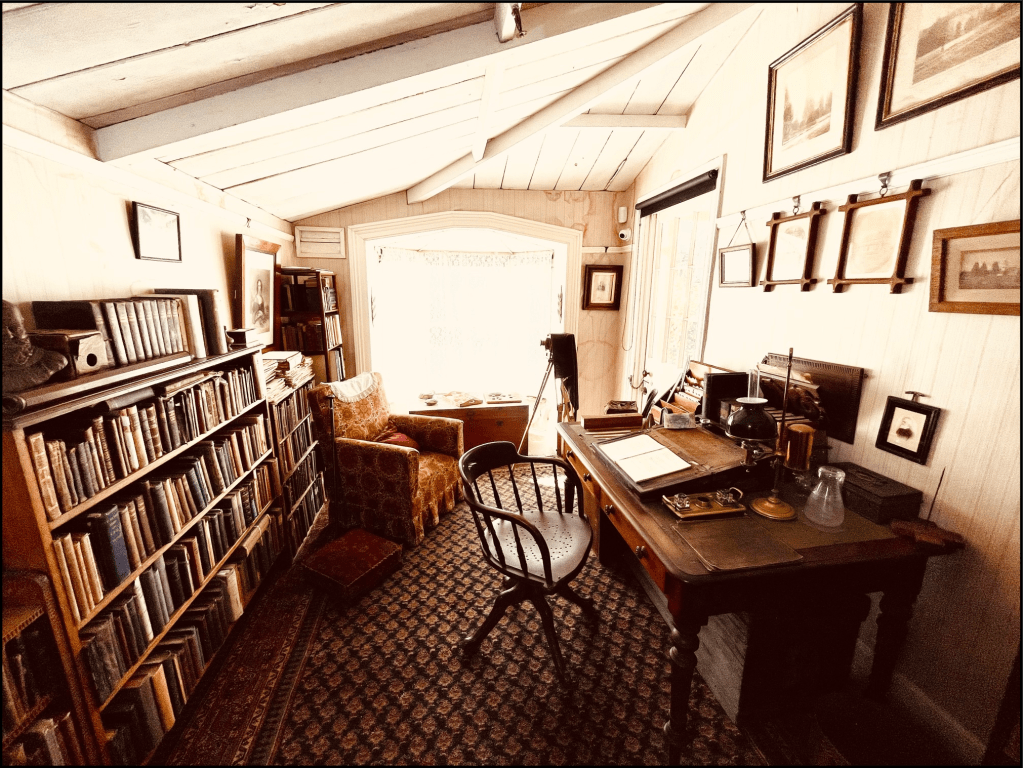

[30] Westcott’s books were also on the shelves of Anglican clergy in Aotearoa New Zealand, a fact I can confirm after visiting the historic home of 19th century Anglican priest the Rev. Vicesimus Lush (1817 – 1882), former vicar of Howick and later Archdeacon of Waikato. I was given permission to look through the books in his study and was not surprised to see several copies of books by Bishop Westcott.

[31] “‘The Word became flesh’ is the central affirmation which underlies all [the evangelist] wrote.” Brooke Foss Westcott, The Gospel According to St. John: The Greek Text with Introduction and Notes, Vol 1 (London: John Murray, 1908), xxxiii. Westcott was a part of another triumvirate of Anglican Johannine scholars, including Joseph Barber Lightfoot and Fenton John Anthony Hort, who all underscored the Incarnation in their scholarship. See Stephen Neil and N. T. Wright, The Interpretation of the New Testament, 1861 – 1986 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988), 35. I intentionally use the phrase “every syllable” in reference to the following quote from Westcott: “Every syllable, as Origen said, has, I believe, its force and the words [of Scripture] are living words for us.” A. Westcott, Life and Letters of Brooke Foss Westcott, vol II (London: Macmillan, 1903), 75, as cited in Rowan Williams, Anglican Identities (Lanham MD: Cowley, 2003), 140.

[32] “The idea of Christ as a mere phantasm, without human flesh and blood, was to [the evangelist] destructive of the Gospel…A characteristic feature of the Fourth Gospel is its frequent insistence on the true humanity of Jesus. He is represented as tired and thirsty (4:6-7; 19:28). His emotion of spirit is expressed in His voice (11:33). He wept (11:35). His spirit was troubled in the anticipation of His Passion (12:27; 13:21). And the emphasis laid by John on His ‘flesh’ and ‘blood’ (6:53), as well as on the ‘blood and water’ of the Crucifixion scene, shows that John writes thus of set purpose. At one point (8:40) John attributes to Jesus the use of the word anthropos as applied to Himself.” John Henry Bernard, A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Gospel According to St. John (Edinburgh: T & T Clark, 1928), 20.

[33] Sir Edwyn Clement Hoskyns, The Fourth Gospel (London: Faber and Faber Limited, 1947), 52. “The author speaks with authority because he knows that in the very kernel of the apostolic gospel there is a scandal to sensitive souls…The scandal of apostolic Christianity, the stumbling block, is the concrete, historical [flesh and blood] figure of Jesus…those ancient spiritual and prophetic men were…in revolt against the possibility that flesh, concrete human and visible flesh, could be of any essential or permanent importance for a truly spiritual religion.”

[34] Several translators prefer to use “external” facts, but the Greek word used by Eusebius is somatika, which means “bodily”: “John, last of all, conscious that the bodily facts had been set forth in the [Synoptic] Gospels, was urged on by his disciples, and divinely moved by the Spirit, composed a spiritual Gospel” Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History Books 6 – 10, trans. J.E.L. Oulton (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 1932) LCL 265,VI.xiv.7, p. 48 – 49.

[35] Sir Edwyn Hoskyns, The Fourth Gospel, edited by Francis Noel Davey (London: Faber and Faber, 1947), 17.

[36] William Temple wrote his Readings in St. John’s Gospel before beginning his two-year stint as the Archbishop of Canterbury. In his commentary, he puts the Fourth Gospel in dialogue with his own personal experience of Christ in order to let the Holy Spirit speak to him through the narrative. William Temple, Readings in St. John’s Gospel, xiii. Although parts of the commentary may seem dated today, it remains a spiritual classic because, with this personal and meditative approach, he generally avoids getting caught up in the changing tides of biblical scholarship. Rupert Hoare, “William Temple’s Readings in St. John’s Gospel and Social Ethics” in Crucible: The Journal of Christian Social Ethics, Jan.-Mar. 2003, Norwich: Hymns Ancient and Modern, 299, as cited by Stephen Spencer, Archbishop of Canterbury: A Study in Servant Leadership (London: SCM Press, 2022), 162. Like his predecessors, Temple affirms the central importance of the Incarnation, even claiming that the most crucial and critical phrase in all of Christianity is: “The Word became flesh.” William Temple, Nature, Man and God: Gifford Lectures, Lecture XIX: ‘The Sacramental Universe” (London: Macmillan), p. 478 as cited in Christ In All Things: William Temple and His Writings, ed. Stephen Spencer (Norwich: Canterbury Press, 2015), 130. Because of the Incarnation, Temple said that Christianity is the most “materialistic” of all the great world religions. “Materialistic” not in the economic sense but in its affirmation and celebration of matter. In the introduction to his Readings, Temple explains, “Based as it is on the Incarnation, [Christianity] regards matter as destined to be the vehicle and instrument of spirit, and spirit as fully actually so far as it controls and directs matter.” William Temple, Readings in St. John’s Gospel (London: Macmillan, 1945), xx-xxi. Also in Lecture XIX of the Gifford Lectures, he says, “[Christianity] is the most avowedly materialist of all the great religions” as cited in Christ In All Things: William Temple and His Writings, ed. Stephen Spencer (Norwich: Canterbury Press, 2015), 130. Temple also challenges the idea that the Incarnation was a form of divine condescension, that the high and lofty God condescended to the low and disdainful condition of miserable human beings. “Incarnation,” he says, “is the only way in which divine truth can be expressed, not because of our infirmity because of its own nature. What is personal can be expressed only in a person.” William Temple, Readings in St. John’s Gospel (London: Macmillan, 1945), 231. For Temple, John’s Prologue clearly teaches that God loves physical matter. God made it, God became it, and God wants us to experience God’s self through it. Temple also seemed to affirm and celebrate the goodness of matter in his own personal life because along with a weakness for John’s Gospel, he also had a weakness, according to his biographer, for strawberry ice cream. Apparently, Temple’s passion for Fragaria contributed to his expanding waistline so much so that the dry cleaners mistook his wide liturgical vestment for a bell tent. Stephen Spencer, Christ in All Things: William Temple and his Writings (Canterbury, 2015), xiii.

[37] Bishop John A. T. Robinson (1919 – 1983) sadly followed in the footsteps of Sir Edwyn Hoskyns as well as Henry Scott Holland, Robert Henry Lightfoot and even the Venerable Bede in the fact that he passed away before completing his work on John’s Gospel. However, his unfinished commentary reveals how faithfully he followed in the footsteps of the Anglican Johannine scholars who underscored the Incarnation. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, German scholar Ernst Käsemann and Dutch scholar Marinus de Jonge characterized the Johannine Jesus as “a detached god who seems to glide across the face of the earth” and as an aloof “stranger from heaven.” Ernst Käsemann, The Testament of Jesus: According to John 17, trans. Gerhard Krodel (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1968), 75. Marinus de Jonge, Jesus: Stranger from Heaven and Son of God: Jesus Christ and the Christians in Johannine Perspective (Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1971). Käsemann argues that the author of the Fourth Gospel exhibits Gnostic and Docetic tendencies, portraying Jesus as more of an ethereal spirit who only appears to be human. Robinson finds no convincing evidence for this argument, explaining that John had no interest at all in discarding or demeaning the flesh, but only in “allowing it to become diaphanous to spirit.” Robinson, The Priority of John (Eugene OR: Wipf & Stock, 1985), 345. Like Hoskyns, Robinson takes St. Clement of Alexandria to task for creating a false dichotomy between the spiritual and the bodily. John’s primary theological concern, according to Robinson, is to shatter this dichotomy, which his Gnostic opponents seem to uphold. John insists that when the Word became flesh, the spiritual became bodily and sensual. Robinson, The Priority of John (Eugene OR: Wipf & Stock, 1985), 344.

[38] Barnabas Lindars of St. John’s Cambridge (Bishop Selwyn’s alma mater) echoes Robinson’s rejection of Käsemann’s claim, explaining that God’s full revelation and purpose is only achieved “in the flesh-taking of the Word of God.” Barnabas Lindars, The Gospel of John (London: Oliphants, 1972), 61 – 63, 78.

[39] Anglican biblical scholar Richard Bauckham, who is still publishing today, dedicates a collection of his essays on John’s Gospel to “the memory of the great British Johannine scholars” and then provides a brief list, beginning with Brooke Foss Westcott, followed by Edwyn Clement Hoskyns and then later John Arthur Thomas Robinson and Barnabas Lindars. Richard Bauckham, The Gospel of Glory: Major Themes in Johannine Theology (Grand Rapids MI: Baker Academic, 2015). Bauckham’s list also includes Charles Harold Dodd (Congregationalist) and Charles Kingsley Barrett (Methodist). Although he surprisingly omits William Temple, Bauckham remains within the stream of flesh-affirming Johannine Anglicans by pointing out that, in John, Jesus experiences human fatigue (4:6), thirst (4:6-7; 19:28), affection (11:5; 13:23), anger (11:33,35, 38), anguish (12:27), and anxiety (13:21). Bauckham argues that John not only complements the Synoptics, but functions as “a key” to understanding them. Richard Bauckham, The Gospel of Glory: Major Themes in Johannine Theology (Grand Rapids MI: Baker Academic, 2015), 201.

[40] In an essay titled Anglican Approaches to St. John’s Gospel, Rowan Williams surveys the work of Westcott, Hoskyns, Temple, and Robinson, who each express in their own way what Williams calls “the tough paradox of Johannine faith,” the paradox of a wholly other transcendent reality becoming accessible and tangible to us, in history, as a “fleshly human life.” Rowan Williams, Anglican Identities (Lanham MD: Cowley, 2003), 124, 136.

[41] Richard Schmidt, Glorious Companions: Five Centuries of Anglican Spirituality (Grand Rapids MI: William B. Eerdmans, 2002),xiv.

[42] Dorothy Lee, “The Gospel of John and the Five Senses” Journal of Biblical Literature 129, no. 1 (2010).

[43] Ernst Käsemann, The Testament of Jesus: According to John 17, trans. Gerhard Krodel (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1968), 75. Marinus de Jonge, Jesus: Stranger from Heaven and Son of God: Jesus Christ and the Christians in Johannine Perspective (Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1971).

[44] Dorothy Lee, “The Gospel of John and the Five Senses” Journal of Biblical Literature 129, no. 1 (2010), 127.

[45] Dorothy Lee, Flesh and Glory: Symbolism, Gender, and Theology in the Gospel of John (New York: Herder and Herder, 2002).

[46] Dorothy Lee, Flesh and Glory: Symbolism, Gender and Theology in the Gospel of John (New York: Herder and Herder, 2002), 36. This symbol is often overlooked. For example, Craig Koester does not acknowledge human flesh as a symbol in his otherwise excellent book Symbolism in the Fourth Gospel. If the human flesh of Christ functions as a vehicle of God’s glory, then all the earthy components of his flesh participate in that functioning as well. Theologian Elizabeth Johnson reflects on this mystery when she writes: “Born of a woman (Gal 4:4) and the Hebrew gene pool, Jesus of Nazareth was a creature of earth, a complex unit of minerals and fluids, an item in the carbon, oxygen and nitrogen cycles, a moment in the biological evolution of this planet. Like all human beings, he carried within himself the signature of the supernovas and the geology and life history of the Earth. The atoms comprising his body once belonged to other creatures.” Elizabeth Johnson, “Deep Incarnation: Prepare to be Astonished,” paper given at the VI International UNIFAS Conference, Rio de Janeiro, July 7 – 14, 2010, https://sgfp.wordpress.com/2011/02/15/deep-incarnation-prepare-to-be-astonished/. This is a description of what theologians call “deep incarnation,” which is the idea that God came to the world in Jesus not only as a human to save humans, but as a living, material being to save all living things together with the entire cosmos. We may understand this deep incarnation as a way of describing, in Māori terms, Christ’s cosmic whakapapa. God did not become incarnate in a human body on this earth to cut us off from our human bodies and from the earth and snatch us up to some distant heaven. God became incarnate as a human so that we might become fully human and more fully alive in our human bodies on this earth and then eventually in our resurrected bodies. St. Irenaeus said, “The glory of God is a human being fully alive.” Although we do not know all the details and mechanics of it, we know that God’s plan is not to discard this earth, but rather to bring heaven to earth, which is why Christ taught us to pray, “May your kingdom come and your will be done on earth as it is in heaven.” Hildegard of Bingen said, “If we fall in love with creation deeper and deeper, we will respond to its endangerment with passion.” We protect what we love. The Gospel of John invites us to love and affirm and thus protect what God loves and affirms: our human bodies and this earth, this world that “God so loved” (John 3:16).

[47] Thomas Ryan, Reclaiming the Body in Christian Spirituality (Paulist Press: Mahwah NJ, 2004), xi.

[48] Scott MacDougall, The Shape of Anglican Theology: Faith Seeking Wisdom (Leiden: Brill, 2022),104.

[49] Scott MacDougall, The Shape of Anglican Theology, 120.

[50] This approach has, in fact, led to the preservation of cultures that might have otherwise been lost. Thanks to the Anglican Church, the Welsh language was preserved in the 16th century. Likewise, the Yoruba and Baganda languages of Africa were preserved in the 19th century, to name a few. Kevin Ward, A History of Global Anglicanism, 24. The Thirty-Nine Articles, which have historically conveyed the theological essence of our Anglican identity, offer some guidance in helping us participate in the Missio Dei. The Rev. Dr. John Kater, an Anglican missionary in Panama, stressed the importance of Article XXXIV (34) which reads: “It is not necessary that Traditions and Ceremonies be in all places one, or utterly like; for at all times they have been divers, and may be changed according to the diversity of countries, times, and manners, so that nothing be ordained against God’s Word….so that all things be done to edifying.” According to Kater, this article captures, in many ways, the unique charism of Anglicanism, which at its best, does not emphasize the English language and culture in worship, but the vernacular language and culture in worship. It is this emphasis that has inspired Anglican missionaries to help preserve the unique languages of rich cultures. “Gregory’s famous directive to adapt pagan sites and practices to Christian devotion rather than destroy them suggested a creative stance towards preexisting religions and cultures for mission in and from Britain, and it anticipated discussions of the scope and limits of syncretism and enculturation that have recurred in Anglican mission.” Titus Presler, “The History of Mission in the Anglican Communion” in The Wiley-Blackwell Companion to the Anglican Communion, 16.