This paper was presented at the Annual Meeting of the Colloquium on Violence & Religion at the Institut Catholiqe de Paris on June 14, 2023.

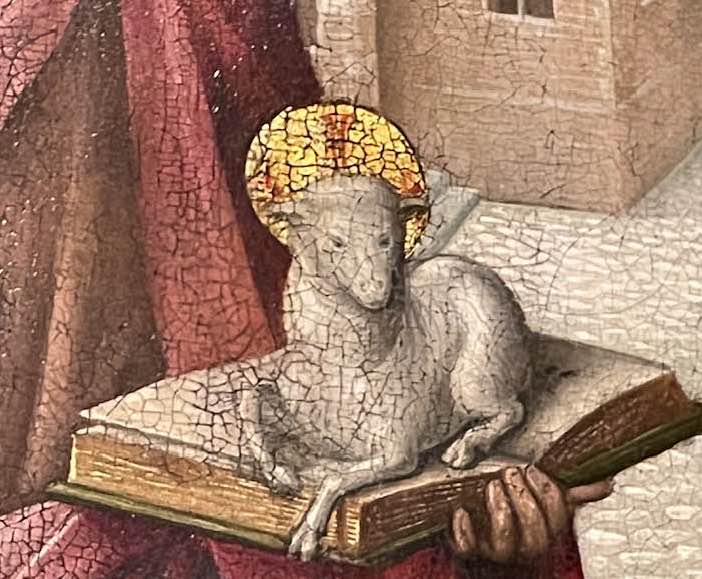

The Divine Prank of the Paschal Lamb:

Putting Meat on Gil Bailie’s Interpretation of Exodus 12

In his book Violence Unveiled, Gil Bailie offers an interpretation of Exodus 12 that can be considered a “Girardian Midrash,” an exegetical commentary on a biblical text informed by the insights of Mimetic Theory. He describes ancient Egyptian society as “caught in a violent sacrificial crisis” and then he likens Moses’s response to that of Abraham at the Akedah when he sacrificed a lamb in place of his son Isaac. Similarly, the Tannaitic Rabbi Ishmael, in his Mekhilta midrash, also connects the two biblical accounts, claiming that when God saw the blood of the Passover lamb, he saw the dam akedato shel Yitzchak, the blood of the binding of Isaac.[1] Bailie argues that although Moses attributes the violence of the Passover to Yahweh, it was Moses’s “way of giving Yahweh the credit for the fact that some of the Hebrews managed to escape from the violence of their oppressors.”[2] In this paper, I will use these two “midrashim” to interpret the blood of the paschal lamb as a mischievous and liberating form of deception against the violent religious authorities who, I suggest, demanded proof of child sacrifice from each household. So rather than grieving the loss of their children, the Israelite families enjoyed a delicious lamb dinner with them, having successfully pranked the priests of religious violence.

Proceeding in chronological order, we will first examine the Mekhilta DeRabbi Ishmael, which is a classic Tannaitic midrash on the Book of Exodus.[3] The apparent author Rabbi Ishmael ben Elisha is believed to be a contemporary of the great Rabbi Akiva, who lived from approximately 50 to 135 CE.[4] The Mekhilta begins with commentary on Exodus (Shemot) chapter 12 verse 3, when the content of Shemot transitions temporarily from aggadah (narrative) to halakhah (law). Rabbi Ishmael comments on Exodus 12:13 in Mekhilta Pischa 7, I 56, saying, “WHEN I SEE THE BLOOD (Ex 12:13), I see the blood of the binding of Isaac, as it is said AND ABRAHAM NAMED THAT SITE THE LORD WILL SEE (Gen 22:14). Similarly it says… AS HE WAS ABOUT TO WREAK DESTRUCTION, THE LORD SAW AND RENOUNCED FURTHER PUNISHMENT AND SAID TO THE DESTROYING ANGEL, “ENOUGH! STAY YOUR HAND!” (1 Chronicles 21:15). What did he see? He saw the blood of the binding of Isaac as it was said THE LORD HIMSELF WILL SEE THE SHEEP (Gen 22:8).[5]

According to this classic Tannaitic midrash, when God sees the blood of the paschal lamb on the lintel of the door, he sees the blood of the binding of Isaac. Although Rabbi Yehudah argues that the blood of the Akedah was indeed the blood of the sacrificed Isaac who died and rose again,[6] the dominant understanding is that the blood of the Akedah was the blood of the lamb, which the LORD provided as a sacrifice in place of Isaac. Since Abraham was willing to sacrifice his son Isaac to the LORD, it is believed that the blood of the lamb was accepted by God as if it were the blood of Abraham’s beloved son Isaac. So, when God sees the blood of the paschal lamb, he remembers the merit of Abraham’s willingness to sacrifice his son, thus persuading God to extend mercy to Abraham’s descendants in Egypt.[7] However, a Girardian interpretation of the Akedah would suggest that Abraham offered a more radical and transformational sacrifice than that of his son. Instead of sacrificing his son Isaac in a violent act of mimetic acquiescence to the religions of sacrificial violence, Abraham exhibited a more radical willingness to sacrifice his understanding of God as a bloodthirsty deity. Indeed, Abraham was ready to imagine his God as a deity who offered God’s very self in generous love to liberate humanity from its bloodthirsty compulsions. This Girardian interpretation can be supported by the Mekhilta’s subsequent comments on Exodus 12:13, which underscore a tension between a god of violent punishment and a God of mercy and providence by highlighting an intertext: 1 Chronicles 21:15, a verse in which God, who is identified as Elohim, sends an angel to destroy Jerusalem while the Lord, who is identified as YHWH, renounces the violence of the malak hamashchit (angel of destruction), saying, Rav atah hereph yadekah (Enough! Stop your hand!). So, in commenting on the malak hamashchit of Exodus 12, Rabbi Ishmael references the malak hamashchit of First Chronicles and highlights the biblical author’s expression of a tension and even confrontation between the punitive god named Elohim and the actively non-violent God known as YHWH.

Rabbi Ishmael then repeats the initial assertion: “He saw the blood of the binding of Isaac,” followed by a reference to the Akedah itself in Genesis: THE LORD HIMSELF WILL SEE THE SHEEP (Gen. 22:8). This biblical verse is generally understood to mean that God will provide the sheep, which is Abraham’s answer to his son’s question about the sacrifice on Mount Moriah: “Father, I see the fire and wood, but where is the lamb for the burnt offering?” (Gen 22:7). However, as Scott Hahn reminds readers in his book The Lamb’s Supper, “Recall that there was no punctuation in the Hebrew original, and consider an alternative reading of verse 8: ‘God will provide Himself, the Lamb, for a burnt offering.”[8] This reading suggests that somehow God offers Godself in the form of a lamb to Abraham so that the burnt offering can be made without any human blood being shed at all.

So, in this brief pischa of the earliest extant midrash on Shemot, we see three key features: (1) the blood of the paschal lamb being linked to the blood of the Akedah; (2) a confrontation between a bloodthirsty god and an actively nonviolent deity, and (3) an expression of God’s self-donation in the form of a lamb to meet the requirements of a sacrificial offering. With these features of an ancient Jewish midrash in mind, we can proceed to a modern “Girardian midrash” articulated by Gil Bailie in Violence Unveiled.

First, what do I mean by “Girardian midrash”? Midrash is both “a method of study and interpretation of the Bible” as well as “the name given to the literary works that emerge from that study.” So, a midrash is both the interpretive comment on a work or a verse and also “the book in which these individual pericopes have been incorporated.”[9] According to Renee Bloch, midrash is (1) a meditation on the Bible, (2) is homiletical, (3) employs a form of intertextuality that uses one part of the Bible to explain another part of the Bible, (4) makes the biblical message relevant to the times, and (5) seeks the true significance or the basic legal principles within a biblical passage. I argue that a Girardian midrash includes all five characteristics while also being intentionally informed by the insights of Mimetic Theory. In his Girardian midrash, Bailie writes,

“Just as Abraham glanced up to see a ram caught in a thicket, Moses glanced up and saw Egyptian society caught in a violent sacrificial crisis. Many people were dying. The specter of death was palpable. Moses seized the interpretive possibilities this situation provided as deftly as Abraham seized the ram on Mount Moriah. If the ‘Passover’ meal inaugurates Israelite culture under Moses, then Israel’s founding event was not an act of sacrificial violence, but an act of Mosaic interpretation. Just as the biblical God created the world, not violently, but by speaking, the Bible’s first political leader created culture, not by sacralizing his own community’s mob violence, but by interpreting violence unleashed by others. Whatever the nature of the violence from which the Hebrews in Egypt cowered in dwellings whose doors were marked in blood to ward it off, and whatever might have kept that violence from taking its anticipated toll of Hebrew lives, the violence that accompanied Israel’s initial act of cultural self-consciousness was not committed by those who discovered their religious identity under its pall. The fact that Moses interpreted the violence as the work of Yahweh is a ‘myth’ in one sense, but it is not mythological in the way in which I [Gil Bailie] am using that term. It was not an attempt to camouflage Hebrew founding violence. Rather, it was a way of giving Yahweh the credit for the fact that some of the Hebrews managed to escape from the violence of their oppressors.”[10]

Like Rabbi Ishmael in his Mekhilta midrash, Bailie draws a connection between the paschal lamb and the lamb of the Akedah. While Abraham seized the ram on Mount Moriah, Moses seized “the interpretive possibilities” that the violent situation had provided. Although Bailie remains intentionally vague in describing the precise nature of the violent situation, the “interpretive possibilities” which Moses seized resonate with the second feature I highlighted above from the Mekhilta midrash: a tension and even confrontation between a violent power and a power that rescues others from violence. Rabbi Ishmael references 1 Chronicles 21:15 in which YHWH resists the violence of malak hamashchit sent by Elohim, saying “Stop your hand!” and thus rescues Jerusalem from destruction.[11] Similarly, Bailie sees Moses interpreting the violence as the work of YHWH not in the mythological sense, but as “a way of giving Yahweh credit for the fact that some of the Hebrews managed to escape from the violence of their oppressors.” In this way, Bailie attributes the violence of the Passover not to God, but to the Hebrew people’s oppressors. While remaining vague about the precise nature of this violence, Bailie understands God being portrayed by Moses as the one who rescues his people from the violence.

Like Abraham, Moses offered a sacrifice far more radical and transformational than the bloody sacrifice of the firstborn sons. He sacrificed his understanding of a bloodthirsty god on the altar of inspired interpretation and an expansive imagination unbound by death. This imagination was rooted in an understanding of God who brought life and creation into being not through violence but through speaking, through the giving of himself through his Word.[12] So, we see that Bailie’s Girardian midrash shares at least two of the three key features I highlighted above in Rabbi Ishmael’s midrash: a link between the lamb of the Akedah and the paschal lamb as well as a confrontation or tension between a violent power and a power that prevents violence.

Bailie seems to understand the violence of the malak hamashchit as “violence unleashed by others.” For the remainder of this paper, I will suggest an anthropological interpretation of the violence attributed to the malak hamashchit. Informed by the shared insights of these two midrashim, I will take Bailie’s interpretation a step forward by putting some meat, so to speak, on his Girardian midrash and offering a possibility for the violence which he keeps vague. I will suggest how the malak hamashchit may have functioned in an anthropological sense during the first Passover.

A New Girardian Midrash

The Book of Exodus (Shemot) begins with a description of the Egyptians as the oppressors of the sons of Jacob, whom the new king of Egypt knew not (Exodus 1:8). The growing population of the Israelites aroused anxiety within the king, who believed it wise to impose oppressive slave masters over them to make their lives bitter with harsh labor (1:9 – 14). The king then orders two Hebrew midwives–Shiphrah and Puah–to murder all the baby boys after they have helped the mothers give birth (1:15 – 16). The midwives, however, revere a God who abhors the slaughter of children (Jeremiah 19:1 – 7) so they utilize a form of mischievous deception to protect the innocent baby boys, explaining that Hebrew women are “more vigorous than Egyptian women and give birth before the midwives even arrive” (1:19). This bold act of creative and deceptive nonviolent resistance compels Pharaoh to order every Hebrew boy to be thrown into the Nile River.

I summarize this opening story of Shemot to highlight the following characteristic tendencies of Pharaoh and the Hebrew leaders from a literary perspective: First, Pharaoh responds to his anxiety regarding the Israelites by commanding the slaughter of innocent children. Second, the Hebrew leaders protect the innocent through clever deception. And third, the Hebrew leaders are inspired to engage in creative nonviolent resistance by their belief in God (Exodus 1:17). These three features are explicitly described in the first chapter of Exodus.

When we turn our attention to Exodus chapter 12, we can imagine these same characteristic tendencies at play. After being pummeled by nine disastrous plagues, which would have damaged the Egyptian economy and the people’s sense of stability and wellbeing, Pharaoh is likely riddled with anxiety. The reader of Exodus already knows what Pharaoh is capable of doing when driven by anxiety.

According to anthropologists (especially Girardian anthropologists), communities often resort to scapegoating during times of crisis and catastrophe; and in ancient times, communities would often resort to a blunter force of scapegoating known as human sacrifice. The ancient Egyptians likely believed that the plagues were evidence that their gods were upset with them and needed to be appeased through some form of bloody sacrifice. So, the religious leaders of Egypt likely reverted to the worst kind of human sacrifice: child sacrifice, which is not hard to imagine since the first chapter of Exodus describes the Pharaoh’s orders to drown every Hebrew boy in the Nile River (Ex 1:22). But now it appears that everyone in Egypt (including the Pharaoh himself) was required to sacrifice their firstborn son to appease the angry gods. And so, to ensure that every house obeyed this dreadful ordinance, we can imagine the Egyptian religious leaders or priests requiring each family to show proof of their obedience by wiping the blood of their firstborn son on the lintel of their door. If there was no blood seen on the door, the Egyptians priests would have to perform the dreadful ritual themselves, thus functioning collectively as the malak hamashchit, the Messenger of Destruction.[13]

In Exodus 12, we see Pharaoh responding to his anxiety regarding the Israelites in a similar way in which he responded in chapter one: by commanding the slaughter of innocent children, but this time the slaughter includes the children of Egypt, even his own firstborn son. Considering the midrashim of Rabbi Ishmael and Gil Bailie, we can begin to see in Exodus 12 the second feature I highlighted in Exodus 1: the Hebrew leaders, this time Moses, employing clever deception to protect the innocent children. Like the Hebrew midwives who deceived Pharaoh to keep the young boys alive, I suggest that the blood of the paschal lamb may have functioned as an effective form of deception against Egypt to protect the Israelites’ firstborn sons. Also like the Hebrew midwives, Moses is inspired to engage in this creative nonviolent resistance because of his belief in a God who rejects child sacrifice. Perhaps he remembered the story of Abraham who struggled to obey God by sacrificing his son Isaac and then ultimately learned how to offer a greater sacrifice in letting go of his preconceptions of God as violent and bloodthirsty. God affirmed Abraham’s sacrifice and rejection of divine violence by providing a lamb and even offering Godself as a lamb in place of Isaac for the whole burnt offering. In Bailie’s words, Moses “seized the interpretive possibilities this situation provided as deftly as Abraham seized the ram on Mount Moriah.”[14]

So, just like their father Abraham, the Israelites sacrifice a lamb instead of their firstborn son; and when the priests of Egypt, functioning collectively as the malak hamashchit,approach the houses of the Israelites and see the blood on the door, they conclude that the sacrifice of the firstborn son has been made and they thus pass over the house and proceed to the next one. Meanwhile, the Israelite families are inside their home not grieving over the loss of their firstborn sons, sacrificed to appease a bloodthirsty god; rather, the Hebrew families are enjoying a delicious lamb dinner with their beloved children because they believe in a God of life and liberation and self-giving love.

In returning to the three key features shared by Rabbi Ishmael and Gil Bailie, we can see, in this new Girardian midrash: first, a link between the blood of the paschal lamb and the blood of the Akedah. In both cases, the blood is shed in place of the blood of innocent children in order to protect the lives of the innocent children: first Isaac and then the Israelites’ firstborn sons. When God sees the blood of the Passover lamb, he sees it functioning in the same way as the blood of the Akedah. The second feature was a confrontation between a bloodthirsty god and a protective, nonviolent deity or a violent power and a power that actively prevents violence. In this new Girardian midrash, we can see a confrontation between the gods that demand child sacrifice and the God of Israel who abhors the practice and who essentially says to the religious authorities who seek to carry out the ritual, Rav atah hereph yadekah (Enough! Stop your hand!). However, he does this nonviolently albeit deceptively.

Finally, the third key feature was an expression of God’s self-donation in the form of a lamb. As Scott Hanh and others have pointed out, we can read the original Hebrew of Genesis 12 as saying that God offered Godself as the lamb for the burnt offering. When it comes to the Passover Lamb, the Gospel of John identifies Jesus as the “Lamb of God” (John 1:29).[15] Christ’s crucifixion occurs during the slaughtering of the Passover lambs while John’s Gospel goes so far as to have Jesus on the cross receiving wine on a branch of hyssop (John 19:30), the same branch that was used to wipe the lamb’s blood on the door (Exodus 12:22). Although this new Girardian midrash may generate more questions than answers, it may also help us to see the Gospels themselves as a kind of midrash, inviting us to understand God’s self-giving love in the form of the Paschal Lamb, who continues to protect innocent lives by exposing and dismantling systems of political and religious violence through the playful power of a death-defying prank.

[1] v’raiti et hadam rueh ani dam akedato shel Yitzchak – וראיתי את הדם רואה אני דם עקדתו של יצחק

[2] Gil Bailie, Violence Unveiled: Humanity at the Crossroads (New York: Herder & Herder, 1996), 144.

[3] “Tannaitic Midrash” refers to midrash attributed to the Tannaim, the rabbinic sages who taught from around 10 to 200 CE and whose views are recorded in the Mishnah. The Tannaitic period followed the Zugot (“pairs”) period and preceded the Amoraim (“interpreters”) period.

[4] The edition I will be using is Mekilta de-Rabbi Ishmael, ed. Jacob Z. Lauterbach, Philadelphia, 1949, which is the edition used by Reuven Hammer in The Classic Midrash: Tannaitic Commentaries on the Bible (Mahwah NJ: Paulist Press, 1995). I also consulted the Mekhilta DeRabbi Yishmael, translated by Rabbi Shraga Silverstein, available online at sefaria.org.

[5] Mekhilta Pisha 7, I 56 from The Classic Midrash: Tannaitic Commentaries on the Bible, translated by Reuven Hammer (Mahwah NJ: Paulist Press, 1995), 57. Hammer adds the final phrase: “as it was said THE LORD HIMSELF WILL SEE THE SHEEP (Gen 22:8).”

[6] “Rabbi Jehudah said: ‘When the blade touched his neck, the soul of Isaac fled and departed, (but) when he heard His voice from between the two Cherubim, saying (to Abraham), “Lay not thine hand upon the lad” (Gen. 22:12), his soul returned to his body, and (Abraham) set him free, and Isaac stood upon his feet. And Isaac knew that in this manner the dead in the future will be quickened. He opened (his mouth), and said: “Blessed art thou, O Lord, who quickeneth the dead.”’” Pirkei DeRabbi Eliezer 31:10.

[7] “The Sages emphasize that this verse (Exodus 12:13), like so many others, is not to be taken literally. Obviously God needs no sign in order to know where the Israelites are. Therefore the verse must mean either that He commanded them to do this in order to give the Israelites an opportunity to earn redemption through performance of mitzvot or, connecting the word blood here with a different blood, namely that of Isaac, since, according to other midrashim, Isaac’s blood was actually shed upon the altar. Thus saying that God ‘sees’ the blood means that He recalls the merit of Isaac’s sacrifice.” Reuven Hammer, The Classic Midrash, 57 – 58.

[8] Scott Hanh, The Lamb’s Supper: The Mass as Heaven on Earth (New York: Doubleday, 1999), 18.

[9] Reuven Hammer, The Classic Midrash: Tannaitic Commentaries on the Bible, 14.

[10] Gil Bailie, Violence Unveiled, 144.

[11] “Then the LORD spoke to the angel, and he put his sword back into its sheath” 1 Chronicles 21:27

[12] Gil Bailie, Violence Unveiled, 144.

[13] For a historical study of sanctioned killing in ancient Egypt, see Kerry Muhlestein, Violence in the Service of Order: The Religious Framework for Sanctioned Killing in Ancient Egypt, British Archaeological Reports International Series 2299 (Oxford: Archaeopress, 2011). Notwithstanding evidence for sanctioned killing in ancient Egypt, I am not making an historical argument in this paper as much as I am offering a literary and anthropological interpretation based on the insights of René Girard and building upon the previous midrashim of Rabbi Ishmael and Gil Bailie.

[14] Gil Bailie, Violence Unveiled, 144.

[15] According to New Testament scholar Sandra Schneiders, “somehow, everything is contained, like the oak in the acorn in this foundational identification [of Jesus as the Lamb of God].” Sandra M. Schneiders, Jesus Risen in Our Midst: Essays on the Resurrection of Jesus in the Fourth Gospel, 153. She also says that this identification functions as “a Johannine hermeneutical sword for cutting through [the] Gordian knot [of Jesus’ death as being simultaneously evil and salvific. Schneiders, 167.