A brief introduction to The Episcopal Church (1888 – 2022) for the Anglican Cycle of Prayer

From 1880 to 1920, the American population would swell from 50 million to 105 million; and this dramatic increase in population brought with it a series of social and economic problems associated with urbanization, industrialization, an economic depression, and dangerous working conditions, as well as the first world war.[1]

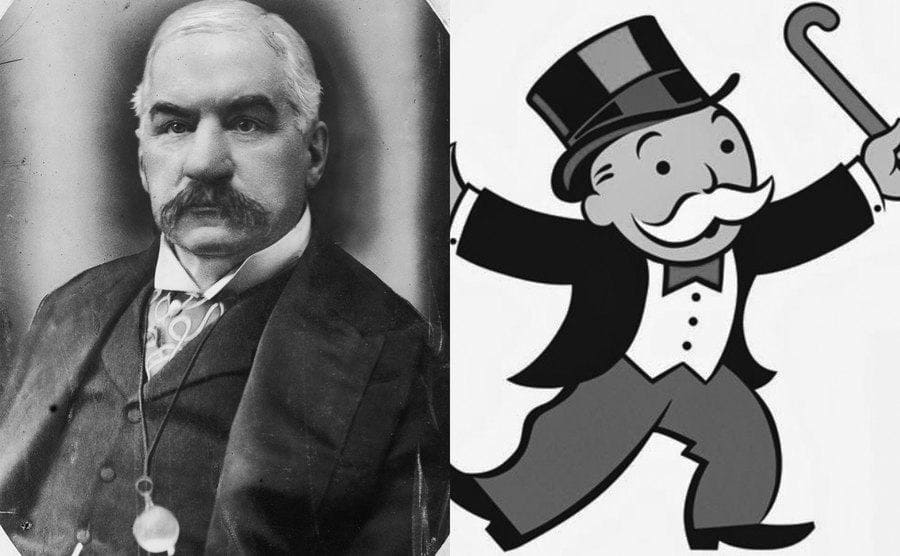

Lifelong Episcopalian and financier J. P. Morgan donated resources to address these problems while also donating money to begin construction of what would become the largest gothic cathedral in the country and one of the largest church buildings in the world: the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York City in 1892.[2]

During this time, educator and activist Vida Dutton Scudder (1861 – 1954) brought the social gospel movement as well as Christian socialism to the attention of the Episcopal Church. Episcopal priest Alexander Crummell (1819 – 1898) founded the American Negro Academy in 1897, the forerunner to the NAACP; and the Episcopal Church assumed a leading role in ministry to the deaf with Thomas Gallaudet (1822 – 1902), offering worship in sign-language. In 1893, an Episcopal seminary on the west coast was founded: Church Divinity School of the Pacific in San Mateo, which later moved to Berkeley. And in 1894, the church set up its national headquarters in New York City. In 1907, construction of the National Cathedral began in Washington DC and in 1910, Grace Cathedral in San Francisco began to be built as the Episcopal Church, which identified as the national church, sought to provide beautiful houses of worship for the American people.

During the Great Depression, previous experiences with social ministry in the church provided models for Episcopalians like Franklin Delano Roosevelt and his Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins who began to address some of the worst ills of the Depression era. Frances Perkins, who was an active Episcopalian, was the first woman to serve in the presidential cabinet.[3] She insisted on social security, worker safety, unemployment insurance, and disability insurance, which were all included in the New Deal, thanks to her.

Although slavery had been outlawed for decades, civil rights were certainly not ensured for all. Even though formal structures of segregation were disappearing in the 1950s, America had in some ways become more segregated in that decade, and that was especially the case within Episcopal parishes. Discrimination in housing, wages, and lending policies meant that few African Americans found homes in the prosperous suburbs and as whites moved to those suburbs, inner-city neighborhoods became increasingly non-white.[4]

In 1961, John Morris (b. 1930) and Cornelius Tarplee formed the Episcopal Society for Cultural and Racial Unity (ESCRU) to address the continued existence of racism and to push the General Convention to take a more active stand on matters of race.

In 1963, Bishops Charles Carpenter and George Murray of Alabama urged Alabama governor George Wallace to follow the direction of the federal courts by allowing integration. However, the bishops also urged civil rights leaders to discontinue public protests and to let racial matters be resolved in the courts, rather than the streets. It was this letter from Episcopal bishops that Martin Luther King Jr. addressed in his own famous “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” in which he said he was “gravely disappointed with the white moderate.”[5]

In his Letter, King goes on to say, “I have almost reached the regrettable conclusion that the [African American]’s great stumbling block in the stride toward freedom is not the [White Supremacist] or the Ku Klux Klanner, but the white moderate who is more devoted to ‘order’ than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice; who constantly says, ‘I agree with you in the goal you seek, but I can’t agree with your methods of direct action;’ who paternalistically feels he can set the timetable for another man’s freedom; who lives by the myth of time and who constantly advises the [African-American] to wait until a ‘more convenient season.’”[6]

These words have continued to haunt and inspire leaders in the Episcopal Church. In 1965, one young Episcopal seminarian named Jonathan Myrick Daniels refused to be a white moderate when he took a leave of absence from Episcopal Theological School to work as an ESCRU-sponsored civil rights worker. On August 20, 1965, after being arrested for participating in a protest, Daniels leapt in front of a teenage black girl named Ruby Sales as a violent white racist named Tom Coleman fired his shotgun at her. 26-year-old Jonathan Daniels was killed instantly. Martin Luther King Jr. later said, “One of the most heroic Christian deeds of which I have heard in my entire ministry was performed by Jonathan Daniels.”

In 1965, Bishop of Texas John Elbridge Hines, who helped found the Seminary of the Southwest in Austin TX in 1952, was elected as the youngest presiding bishop. After hearing King describe the “white moderate” as the largest barrier on the path to an equitable world, Bishop Hines decided to be anything but “moderate.” Because of King and Hines, the late-twentieth century Episcopal Church has been about “about revolution not the status quo.”[7] Attorney and lay theologian William Stringfellow, whom Karl Barth admired, insisted that Christians could not remain uninvolved in the political questions of discrimination and war and peace and still be true to their calling and their baptismal vows.

On July 29, 1974, three retired Episcopal bishops decided not to wait for a “more convenient season” to ordain women to the priesthood. So before female ordination to the priesthood was officially authorized by General Convention, they ordained eleven women to the presbyterate at the Church of the Advocate in Philadelphia. These women became known as the Philadelphia Eleven. On September 7, 1975, four more women were priested in Washington DC. At the 1976 General Convention, women’s ordination to the priesthood was officially approved. In 1977, the first African-American woman, Pauli Murray, was priested; and in 1989, the first female bishop of the Anglican Communion was consecrated who also happened to be African-American: Bishop Barbara Harris.

Also in 1989, Bishop John Shelby Spong of Newark NJ ordained Robert Williams, an openly gay man, to the priesthood. In 1994, the General Convention adopted a resolution that stated, “No one shall be denied access to the selection process for ordination in this Church because of race, color, ethnic origin, sex, national origin, marital status, sexual orientation, disabilities or age.”[8] However, in 1998, the Lambeth Conference passed Resolution 1.10 which “rejected homosexual practice as incompatible with Scripture.”[9]

This tension was put to the test when the openly gay Rev Gene Robinson was elected bishop of New Hampshire in June 2003. Because the Episcopal Church took seriously the authority and voice of the laity, who had especially strong representation in church governance from the church’s founding, the bicameral house of ecclesiastical government—the House of Bishops and the House of Deputies—believed it was reasonable to consent to the consecration of an openly gay bishop because the people of New Hampshire had clearly spoken.

The consecration of Bishop Gene Robinson in November of 2003 led to schism and a breakdown in relationships among bishops and leaders within the Episcopal Church and the entire Anglican Communion, as well as the entire Christian community. The decision to consecrate Gene Robinson flew in the face of Lambeth Resolution 1.10. In response to Robinson’s consecration, a Lambeth Commission on Communion was appointed by the Anglican Communion and published in 2004 a document called the Windsor Report, which recommended an Anglican Covenant for the Anglican Communion, which was ultimately rejected.

The Windsor Report also made a request of The Episcopal Church in paragraph 135, saying, “We particularly request a contribution from the Episcopal Church (USA) which explains, from within the sources of authority that we as Anglicans have received in scripture, the apostolic tradition and reasoned reflection, how a person living in a same gender union may be considered eligible to lead the flock of Christ. As we see it, such a reasoned response…will have an important contribution to make on the ongoing discussion.”[10]

In 2005, the Episcopal Church responded to this request by publishing a document titled “To Set Our Hope on Christ: A Response to the Invitation of Windsor Report Paragraph 135,” a document that explains the church’s position of full inclusion using scripture, tradition, and reasoned reflection. [And I strongly recommend that every Episcopalian and every Anglican read this document.]

During this time, Episcopal parishes and dioceses broke off from The Episcopal Church, joining the Anglican Church in North America, which is not recognized by the Archbishop of Canterbury as part of the Anglican Communion.

In 2008, Bishop Gene Robinson was not invited to the Lambeth Conference although all other bishops in the Anglican Communion were invited. After consecrating Gene Robinson, the Episcopal Church put a moratorium on consecrating openly gay and lesbian bishops, but at the General Convention in 2009 in Anaheim, the church voted to lift the moratorium. And in 2010, Bishop Mary Glasspool, the first openly lesbian bishop, was consecrated. [And on January 11, 2014, I was ordained to the priesthood by Bishop Mary Glasspool at St. John’s Cathedral in Los Angeles.]

In 2015, the Episcopal Church elected its first African American presiding bishop Michael Curry. In that same year, the church voted to affirm same-sex blessings and rights, which led the Anglican Communion to sanction The Episcopal Church (TEC) for three years. TEC remained part of the AC but was not allowed to have representation in the Anglican Consultative Council or serve in any official leadership roles in the Anglican Communion.

These sanctions expired in 2019, and at the Lambeth Conference in 2022, Archbishop of Canterbury Justin Welby wrote a letter to all the bishops of the communion, in which he said, “Given the deep differences that exist within the Communion over same-sex marriage and human sexuality, I thought it important to set down what is the case. I write therefore to affirm that the validity of the resolution passed at the Lambeth Conference 1998, 1.10 is not in doubt and that whole resolution is still in existence. The Call states that many Provinces—and I think we need to acknowledge it’s the majority – continue to affirm that same-gender marriage is not permissible. The Call also states that other provinces have blessed and welcomed same sex union/marriage, after careful theological reflection and a process of reception. What is also clear is that Lambeth 1.10 itself continues to be a source of pain, anxiety and contention among us. That has been very clear over the course of this Lambeth Conference. That is also part of the current reality of our Communion. To be reconciled to one another across such divides is not something we can achieve by ourselves. That is why…I pray that we turn our gaze towards Christ who alone has the power to reconcile us to God and to one another.”[11]

Because of the strong authority given to the laity in the Episcopal Church (which was partly the result of a lack of bishops during the first couple centuries of its existence) and because of the haunting words of Martin Luther King Jr written to Episcopal bishops in his “Letter from a Birmingham Jail,” the Episcopal Church has sought to avoid the danger of being a white moderate church devoted more to order than to justice. The Episcopal Church, in the late 20th century and early 21st century, has, in many ways, sought to uphold justice and inclusion even at the risk of disorder, disruption, and division.

May we keep all this in our mind as we hold the Episcopal Church in our hearts and as we pray this Collect included in the Episcopal Church’s 1979 Book of Common Prayer,

“O God of unchangeable power and eternal light: Look favorably on your whole Church, that wonderful and sacred mystery; by the effectual working of your providence, carry out in tranquility the plan of salvation; let the whole world see and know that things which were cast down are being raised up, and things which had grown old are being made new, and that all things are being brought to their perfection by him through whom all things were made, your Son Jesus Christ our Lord; who lives and reigns with you, in the unity of the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever. Amen.”[12]

[1] Robert W. Prichard, A History of the Episcopal Church: Complete through the 78th General Convention. Third Revised Edition. (New York: Morehouse Publishing, 2014), 221.

[2] J. P. Morgan was the model for the Monopoly guy, rich Uncle Pennybags. So, for better or worse, the Monopoly guy is an Episcopalian!

[3] Frances Perkins regularly made time for retreat at All Saints’ Convent in Catonsville MD. Naomi Pasachoff, Frances Perkins: Champion of the New Deal (New York: Oxford, 1999), 146 – 149.

[4] Prichard, History, 302.

[5] Martin Luther King Jr. “Letter from Birmingham Jail” August 1963. https://www.csuchico.edu/iege/_assets/documents/susi-letter-from-birmingham-jail.pdf

[6] Martin Luther King Jr. “Letter from Birmingham Jail” August 1963. https://www.csuchico.edu/iege/_assets/documents/susi-letter-from-birmingham-jail.pdf

[7] Barney Hawkins and Ian Markham, “The Episcopal Church and the Anglican Communion” in Modern Believing: Church and Society, vol 29, no. 3. The Modern Churchpeople’s Union.

[8] GC 1994 – D007, https://www.episcopalarchives.org/cgi-bin/acts/acts_resolution.pl?resolution=1994-D007

[9] Lambeth Resolution 1.10, https://www.anglicancommunion.org/resources/document-library/lambeth-conference/1998/section-i-called-to-full-humanity/section-i10-human-sexuality

[10] The Lambeth Commission on Communion, “The Windsor Report 2004” https://www.anglicancommunion.org/media/68225/windsor2004full.pdf

[11] https://www.archbishopofcanterbury.org/news/news-and-statements/letter-archbishop-canterbury-bishops-anglican-communion

[12] Book of Common Prayer 1979, pp. 280 (Good Friday), 291 (Easter Vigil), 515 (Ordination of a Bishop), 528 (Ordination of a Priest), 540 (Ordination of a Deacon).

I dedicate these brief introductions to the Episcopal Church to Mary Ann Flanagan (1930 – 2023), a lovely woman who worshipped regularly at Christ Episcopal Church in Eureka CA. Her deep interest and curiosity about the history of The Episcopal Church (TEC) inspired us both to read A History of the Episcopal Church by Robert W. Prichard, a book that helped inform and inspire these three brief introductions: TEC (1579 – 1792), TEC (1792 – 1888), TEC (1888 – 2022).