A brief introduction to The Episcopal Church (1792 – 1888) for the Anglican Cycle of Prayer

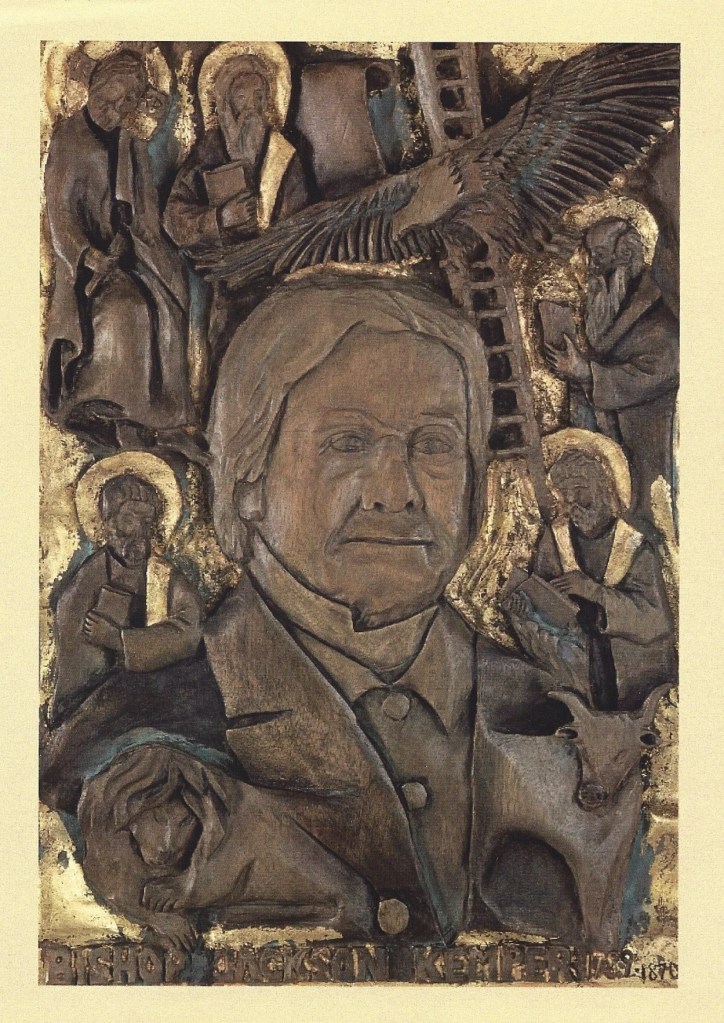

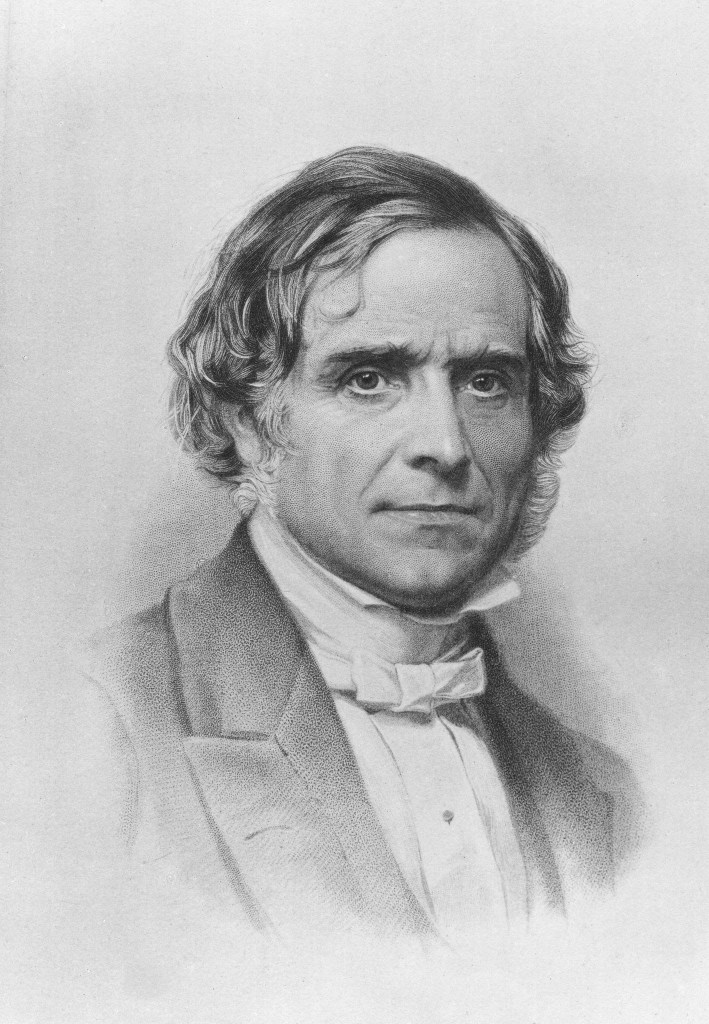

By the end of the eighteenth century, the Protestant Episcopal Church had become one church among several others in the states. In 1817, the General Convention of the church established the General Theological Seminary in New York, the oldest seminary in the Anglican Communion, founded by the Right Reverend John Henry Hobart, the Bishop of New York, who travelled constantly to build up the church and to propagate the importance of episcopacy and apostolic succession.[1] In 1823, the vestry at St. Paul’s Church Alexandria founded the Virginia Theological Seminary, a seminary committed to the evangelical heritage of the Episcopal Church. In 1835, General Convention appointed Jackson Kemper as a missionary bishop out west to Indiana, Missouri, Wisconsin, and Iowa. Kemper championed a more extensive outreach to the Native Americans, endorsing translations of the Scriptures and worship services into Indian languages. Kemper also founded Nashotah House, a seminary in Wisconsin wherein students followed a monastic way of life, waking at 5 AM for prayers, receiving communion weekly, supporting themselves by physical labor and evangelizing the countryside.[2]

General Convention also sent the Right Reverend George Freeman as a missionary bishop to Arkansas, Texas, and Indian Territory in 1844. Freeman, who was formerly the rector of Christ Church in Raleigh North Carolina, rose to fame in the Episcopal Church for preaching a series of sermons and publishing pamphlets that supported slavery, insisting that slavery “was agreeable to the order of Divine Providence” and that “no man, without a new revelation from heaven, was entitled to pronounce it wrong.”[3]

Before the Civil War, “nearly all of the Southern bishops owned slaves” and a group of these bishops got together to establish the University of the South in Sewanee Tennessee in 1857.[4] “The founders’ and trustees’ plan was to make the University of the South a recognized center for the study of race and thereby a sturdy ideological pillar of a civilization based on enslavement of people of African descent.”[5]

“As the wealthiest and most privileged church in America, and the direct descendant of the Church of England,” Spellers writes, “the Episcopal Church was an active supporter of slavery.”[6] In the decades leading up to the Civil War, the Presbyterian, Methodist, and Baptist churches publicly struggled and waged internal battle over the institution of slavery.[7] During the same period, Pope Gregory XVI declared it unconscionable to enslave, persecute or otherwise exploit “Negroes and all other men.”[8] In England, Anglicans like William Wilberforce were at the forefront of the abolitionist movement. So, although there was a growing global Christian consensus against slavery in all the churches in America, the Episcopal Church [in the North and South] was arguably the most willing to continue accommodating slaveholders, traders, and upper-class racists, and the least likely to welcome the equal and full participation of Black people, slave or free.”[9]

Bishop Samuel Wilberforce in England [son of William Wilberforce] looked with shame at his American cousins when he wrote, “The Episcopal Church raises no voice against the predominant evil [of slavery]; she palliates it in theory; and in practice she shares in it.”[10]

The Episcopal Church in the North was arguably as invested in slavery as its Southern counterpart. James DeWolf, a senator of Rhode Island, was an Episcopalian and the most prosperous slave trader in U.S. history. Although Philadelphia boasts the denomination’s first Black church, St. Thomas Episcopal Church, founded by its first Black priest, Father Absalom Jones, the diocese denied the parish a seat in its Diocesan Convention because, according to opposition leaders, “the color, and physical and social condition and education of the blacks, render them unfit to participate in legislative bodies.”[11]

During the Civil War, Bishop John Henry Hopkins of Vermont served as the Presiding Bishop of the Episcopal Church (by virtue of seniority) and wrote a text titled “The Bible View of Slavery” in which he endorsed slavery saying, “Slavery…as maintained in the Southern States, appears to me fully authorized in the Old and the New Testament….That very slavery, in my humble judgement, has raised the Negro incomparably higher in the scale of humanity, and seems, in fact, to be the only instrumentality through which the heathen posterity of Canaan have been raised at all.”[12]

Spellers explains, “During the Civil War, when Southern bishops pulled away to form their own Confederate church, [Presiding Bishop] Hopkins continued to have their names called at every vote in the House of Bishops.[13] After the end of the war…Hopkins helped to reunite the Southern and Northern bishops…the friction in the House was less over slavery and more over the rupture of their unity. The majority of Episcopal bishops and the church’s top clergy and lay leaders consistently supported slavery and the presumption of White superiority.”[14]

There were, however, some voices of dissent within the Episcopal Church when it came to slavery before the Civil War. Presbyterians, Episcopalians, and other interested Christians formed the American Colonization Society in 1816, which followed the British example in Sierra Leone of sending freed slaves to Liberia. Francis Scott Key (Episcopal author of the American National Anthem), President James Madison (a long-time president of the society), and later bishop of Virginia William Meade (1789 – 1862) were among early supporters of the society.[15] ” (Prichard, 150). Also, in 1856, students of Virginia Theological Seminary, including Phillips Brooks (who would later become the famous preacher and rector of Trinity Church in Copley Square Boston) threatened to withdraw if the school did not guarantee protection for students who spoke against slavery since there were rumors that residents of the neighborhood had threatened a student preacher with tar and feathers. The faculty agreed to offer protection and scheduled on-campus discussion about the morality of slavery.[16]

After a long and bloody national war, The Episcopal Church reconciled north and south. During reconstruction, the church continued its general passivity and silence about the sin of slavery. Rather than addressing the aftermath of the war and the need for restoration at home, the church turned to a season of missionary zeal, sending missionaries to South America and Asia and Africa. In 1821, the church founded the Domestic and Foreign Missionary Society. In 1835, the General Convention adopted a new constitution which made membership in the missionary society no longer voluntary but inclusive of all the baptized in the Episcopal Church.

The constitution further declared the world to be the missionary field of the church and entrusted general missionary work to a reorganized board of missions. In 1877 the constitution of the society was enacted as a canon of the General Convention.[17]

One Episcopal missionary was Samuel Isaac Joseph Schereschewsky, who was born of Jewish parents in Lithuania and came into the Episcopal Church as a young man. He became a bishop in China and a translator of the Bible into Chinese. Another was James Theodore Holly, born of African-American parents in Baltimore and brought up as a Roman Catholic and who became a bishop and established in Haiti a church that is equal in size today to the largest American dioceses and plays a central role in the life of that country.[18]

Regarding domestic mission work, Episcopal priest William Augustus Muhlenberg set in motion the development of the New England Episcopal preparatory school, founded the Church of the Holy Communion in New York (which offered Communion each week and was the first to offer free pews) and he also founded St. Luke’s hospital and a women’s order that eventually led to the establishment of the Community of St. Mary, the oldest women’s monastic order in the Episcopal Church. But more than all this, it was Muhlenberg who made the proposal that the Episcopal Church, which claimed apostolic succession, ordain bishops to serve in other churches. This proposal led to the so-called Chicago-Lambeth Quadrilateral, a statement written by William Reed Huntington that proposed that the separated Christian churches should be united around the following four principles: the Bible (the Old and New Testaments), the Dominical Sacraments (Holy Baptism and Holy Communion), the Creeds (the Apostle’s Creed and the Nicene Creed), and the Historic Episcopate.[19] This statement was adopted by the Bishops of the Episcopal Church in Chicago in 1886 and then later in 1888 by the Bishops of the Anglican Communion at Lambeth.

The Chicago-Lambeth Quadrilateral has proven to have significant impact on ecumenical dialogue as well as Anglican identity as it provides a basis for a shared ethos across the global Anglican communion.

[1] “It is often assumed,” Christopher Webber writes, “that the Episcopal Church’s awareness of its catholic heritage is a result of the Oxford Movement, but the early leaders of that movement were directly influenced by American church leaders like John Henry Hobart. Hobart, in turn, reflects the New England experience, which had helped make church members aware of their catholic heritage. Hobart’s writings were known in England, and John Henry Newman, one of the best known of the Oxford leaders acknowledged Hobart’s influence on his thought. Hobart had also travelled in England and met Newman and others of the Oxford leaders. So the Episcopal Church helped shape the Oxford Movement and the Oxford Movement in turn helped shape the American Episcopal Church.” Christopher L. Webber, Welcome to the Episcopal Church: An Introduction to Its History, Faith, and Worship (New York: Church Publishing, 2017), 15.

[2] “Three men, just completing their studies at General Seminary, responded to [Kemper’s] vision [of raising up ministries among the Native Americans] and founded Nashotah House, a new seminary in Wisconsin, giving its life a monastic pattern long before monastic life was reestablished in the Anglican Communion. The students rose at 5 A.M., recited the monastic hours, had weekly Communion, supported themselves by physical labor, and evangelized the countryside for miles around.” Webber, Welcome, 11.

[3] Stephanie Spellers, The Church Cracked Open: Disruption, Decline, and New Hope for Beloved Community (New York: Church Publishing, 2021), 65.

[4] Spellers, Cracked Open, 61.

[5] Spellers, Cracked Open, 62.

[6] Spellers, Cracked Open, 60.

[7] Spellers, Cracked Open, 60.

[8] Pope Gregory XVI, In supremo apostulatus, 1839, https://www.papalencyclicals.net/greg16/g16sup.htm

[9] Spellers, Cracked Open, 60 – 61.

[10] Samuel Wilberforce, A History of the Protestant Episcopal Church in America (London: Rivingtons, 1856), 429, as cited by Spellers, Cracked Open, 145 n. 18. Spellers mistakenly refers to Samuel Wilberforce as “William” Wilberforce on page 61 of Church Cracked Open.

[11] Spellers, Cracked Open, 63.

[12] “Letter from the Rt. Rev. John H. Hopkins, D.D., LL. D. Bishop of Vermont on the Bible View of Slavery,” quoted in Ronald Levy, “Bishop Hopkins and the Dilemma of Slavery,” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 91, no. 1 (January 1967), 65, as cited in Spellers, Cracked Open, 64. The “heathen posterity of Canaan” refers to the 19th century idea that black people were descendants of Ham and his son Canaan, whom Noah cursed when he said, “Cursed be Canaan; the lowest of slaves shall he be to his brothers” (Genesis 9:25). See Stephen R. Haynes, Noah’s Curse: The Biblical Justification of American Slavery (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002).

[13] During the American Civil War (1861 – 1865), Episcopalians met in two separate bodies: the General Convention of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America and the General Council of the Confederate States of America.

[14] Spellers, Cracked Open, 64 – 65.

[15] Robert W. Prichard, A History of the Episcopal Church: Complete through the 78th General Convention. Third Revised Edition.(New York: Morehouse Publishing, 2014), 150. The American Colonization Society sent a record number of freed slaves to Liberia, although “free blacks in the North, such as Absalom Jones and Richard Allen, opposed the efforts of the Colonization Society, both because of the coercion involved and because of the [African American’s] loss of any real connection with African past.” Prichard, History, 151.

[16] Prichard, History. 188. Also see Richard W. Prichard, Hail! Holy Hill! A Pictorial History of the Virginia Theological Seminary (Brainerd, Minnesota: RiverPlace Communications for the Virginia Theological Seminary, 2012), 50.

[17] J. Barney Hawkins, The Wiley-Blackwell Companion to the Anglican Communion (Malden MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2013), 512 – 513. See https://www.episcopalchurch.org/glossary/domestic-and-foreign-missionary-society/

[18] Webber, Welcome, 14.

[19] In the mid 19th century, Anglican theologian Frederick Denison Maurice underscored the following six signs which have been observed by Christians across many centuries, nations, and cultures: baptism, creeds, forms of worship, eucharist, the ordained ministry, and the scriptures. Richard Schmidt writes, “Maurice’s six ‘signs’ have had an interesting history. In 1888, the Lambeth Conference, consisting of Anglican bishops from around the world, adopted the ‘Lambeth Quadrilateral,’ a statement on the basis of which Anglicans invited other Christians to enter into discussions of unity. The Lambeth Quadrilateral…consists of a modified version of Maurice’s six signs of a universal spiritual society. Set forms of worship was dropped, and baptism and eucharist were combined into one sign –resulting in the document which remains to this day the foundational document for all Anglican ecumenical discussions.” Richard H. Schmidt, Glorious Companions: Five Centuries of Anglican Spirituality (Grand Rapids MI: William B. Eerdmans, 2002), 189. For more on F. D. Maurice, see “Listening for Divine Truth with F. D. Maurice.”

I dedicate these brief introductions to the Episcopal Church to Mary Ann Flanagan (1930 – 2023), a lovely woman who worshipped regularly at Christ Episcopal Church in Eureka CA. Her deep interest and curiosity about the history of The Episcopal Church (TEC) inspired us both to read A History of the Episcopal Church by Robert W. Prichard, a book that helped inform and inspire these three brief introductions: TEC (1579 – 1792), TEC (1792 – 1888), TEC (1888 – 2022).