A brief introduction to The Episcopal Church (1579 – 1792) for the Anglican Cycle of Prayer

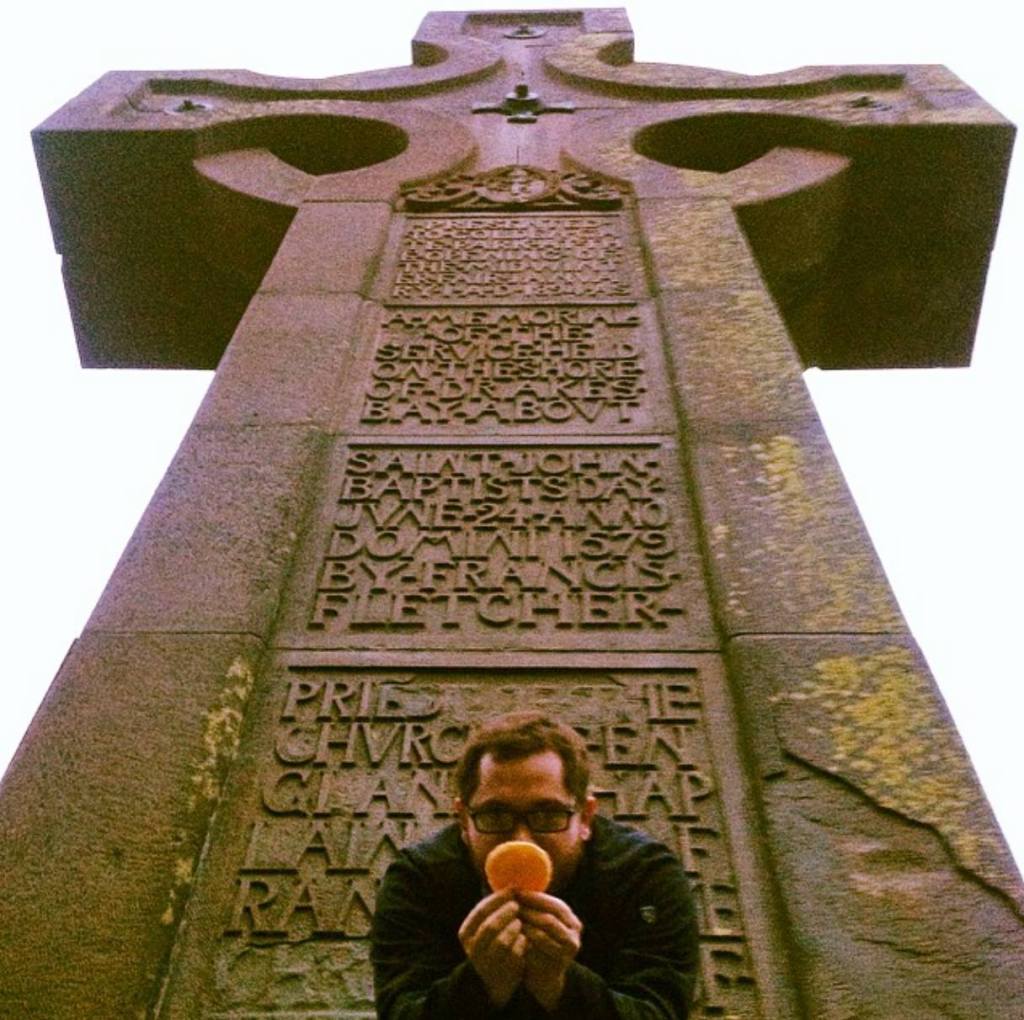

The first recorded worship service using the English Book of Common Prayer on American soil was led by Francis Fletcher, the chaplain of Sir Francis Drake on the Feast Day of St. John the Baptist in 1579. Today, there is a large stone Celtic Cross monument in Golden Gate Park commemorating this event, called the Prayer Book Cross or the Sir Francis Drake Cross. This service took place not long after Sir Francis Drake saw the white cliffs of Point Reyes, which reminded him of the white cliffs of Dover, and called California “Nova Albion.” So, California was New England before New England was New England.

However, it was on the east coast that more permanent British settlements were made. The first attempt at a British colony was led by Sir Walter Raleigh at Roanoke, Virginia (which is now located in North Carolina) in 1585. Mysteriously, the settlers disappeared leaving only the somewhat cryptic message “CROATOAN” carved on a tree, but before they disappeared, they baptized the first Native American Manteo[1] as well as the first English child born in the new world, Virginia Dare.[2]

The first permanent settlement was made in 1607 at Jamestown Virginia, where the colonists were ministered to by their chaplain Robert Hunt. Christopher Webber writes, “With a sail for an awning and a plank nailed between two trees for a pulpit, they made themselves a church and planted the seed from which the Episcopal Church grew.”[3] The charter for the Virginia colony granted by King James I commended the settler’s desire “in propagating of Christian Religion to such People, as yet live in Darkness and miserable Ignorance of the true Knowledge and Worship of God, and may in time bring the Infidels and Savages, living in those Parts, to human Civility, and to a settled and quiet Government.”[4] As this quote demonstrates, during the colonial period of American history, the Native Americans were mostly seen as heathen tribes in need of conversion and their civilization was mostly disregarded. Moreover, the Indians were generally not impressed with the conversion attempts of the “white man.”

The first native convert in Jamestown was the legendary Pocahontas, the daughter of the chief of the area, Powhatan.[5] Although her conversion was widely celebrated, Pocahontas was essentially held hostage and relations with her father Powhatan were dominated by intermittent warfare and rivalry over land. Pocahontas was baptized Rebecca and married John Rolfe on Maundy Thursday April 1, 1613. Later she visited England, where she died of smallpox. Choctaw author Owanah Anderson wrote that it was in the English town of Gravesend that Pocahontas met her end and found her grave.[6]

During the colonial period, no English bishop ever set foot in America; however, the colonies fell under the jurisdiction of the Bishop of London,[7] who commissioned commissaries to represent him. One commissary for Virginia was James Blair who secured a charter in 1693 for a college, which he named after England’s sovereigns, William and Mary. If educating colonists was the nobler side of Anglicanism, its darker side in Virginia was its uncritical connection to the institution of slavery. Blacks were brought unwillingly from Africa to support the economic expansion of the new world, particularly the cotton and tobacco cultures. Colonies like Virginia and South Carolina became dependent on slave labor, and the Anglican Church was largely silent on the human tragedy. In fact, Anglicanism in seventeenth-century America was the strongest in the colonies most dependent on slave labor.

Another commissary appointed by the Bishop of London was Thomas Bray who was charged with exploring ways of developing a more ordered Anglican church life in the American colonies. His brief experience in America led to the creation of the Society of the Propagation of the Gospel (SPG), whose aim was to promote ‘a religious, sober and Polite people.” One of the chief objects of the SPG was to preach the Gospel to native Americans.

Because of England’s lack of direct involvement with the church in America, many vestries in Virginia began selecting their own rectors[8] and so, in the early eighteenth century, “the seeds of American democracy can be seen in the powerful laity who had emerged within American Anglicanism.”[9] In contrast to Virginia and the southern colonies where Anglicanism thrived, Anglicans in New England were a minority and the congregational church predominated while in the more Presbyterian middle colonies Anglicans often became “identified with the ruling elite.”[10] “Anglicanism in New York,” Kevin Ward explains, “ was probably the most prosperous and vigorous in pre-Revolutionary times of all the Anglican communities in America. One reason for this was the wealth of Trinity Church in Lower Manhattan, which was founded as the parish church of New York in 1697. And in 1702, Queen Anne granted the parish a tract of land on the west side of Manhattan, which included what would become Wall Street.[11]

The south, the middle colonies, and New England had their own religious cultures until the Great Awakening in the 1730s and 1740s led by enthusiastic preachers like George Whitefield. This revival brought Presbyterians and Baptists to Virginia and more Anglicans to New England and the middle colonies, thus blurring some of the sharp religious boundaries between the cultures and unifying the soon-to-be new nation.

Also, as revival preachers spoke of the “hand of God” at work in the emerging American culture and its political leaders, the impulse for a war of independence became fueled by religious fervor. Although several prominent Anglican clergy such as the rector of Trinity New York (Charles Inglis) and Samuel Seabury attempted to dissuade public opinion against the Revolution, the British were eventually sent home in 1776 and suddenly the Church of England in the new world was untethered from its cultural and theological moorings.[12] Many loyalist clergy and laity left the thirteen colonies for Canada, Bermuda, or England.

In 1780, priest and college provost William Smith of Maryland began convening gatherings of clergy and laity and by 1783, they had chosen the name “Protestant Episcopal Church” to replace the no longer favored Church of England as the name of their denomination.[13] Also in 1783, Samuel Seabury was elected bishop by the clergy of Connecticut.[14] He was not able to be consecrated bishop in England since he could not take the Oath of Allegiance to the crown as an American. So, he was consecrated by the Nonjuring bishops in the Church of Scotland in Aberdeen on November 14, 1784,[15] under the condition that the Episcopal Church restore the epiclesis in its prayer book’s eucharistic prayer. The epiclesis is the priests’ invocation of the Holy Spirit so that the bread and wine may become the body and blood of Christ and although it was included in Cranmer’s 1549 Prayer Book it was omitted from the 1552 and 1662 prayer books. The Scottish rite included the epiclesis because they believed this practice, which they had borrowed from the Eastern Orthodox liturgy, was truer to the ancient pattern of Christian worship. “The Prayer Book of the new American church,” Christopher Webber points out, “would have links not only to Scotland but also to the Eastern Orthodox Church.”[16]

William White, the second American bishop to be consecrated, later served as the first presiding bishop of the Episcopal Church;[17] and he and Samuel Seabury both later participated in the consecration of Bishop Thomas John Claggett, the first bishop consecrated on American soil, thereby uniting Scottish and English episcopal succession.

Because of the strong vestries which had always been part of the colonial Anglican Church, the Episcopal Church continued to have strong lay representation in its governance. At its first general conventions, the church established two houses of ecclesiastical government to mirror the new national, federal government: the House of Bishops and the House of Deputies (which is composed of clergy and laity). Furthermore, bishops were elected by clergy and laity, not appointed.

By 1792 the Episcopal Church was established as an American denomination. It had a governing body, a prayer book, a national constitution, and a mechanism for the creation of new bishops. As an autonomous church outside of England, the Episcopal Church forever changed what it means to be “Anglican” [18] and its unique emphasis on empowering the laity would later have enormous influence on the global Anglican communion.[19]

[1] Manteo was baptized on August 13, 1587.

[2] Virginia was baptized on August 24, 1587, six days after her birth.

[3] Christopher L. Webber, Welcome to the Episcopal Church: An Introduction to Its History, Faith, and Worship (Church Publishing: New York, 2017), 5 -6.

[4] Charles W. Eliot, ed. American Historical Documents, 1000 – 1904. The Harvard Classics, vol. 43 (P.F. Collier & Son: New York, 1910), as cited in Titus Presler, “The History of Mission in the Anglican Communion” in The Wiley-Blackwell Companion to the Anglican Communion, ed. Ian S. Markham et. al (Wiley-Blackwell: Malden MA, 2013), 17.

[5] Pocahontas was born around 1596 and named “Amonute” though she also had a more private name of Matoaka. She was called “Pocahontas” as a nickname which meant “playful one.” According to Robert W. Prichard, “Most of the Native Americans in Virginia were part of a confederation of predominantly Algonquin-speaking tribes led by Wahunsonacock (Powhatan) that may have been created as a result of a conflict with the Spanish Jesuits, missionaries who reached Virginia in about 1570.” Robert W. Prichard, A History of the Episcopal Church: Complete through the 78th General Convention. Third Revised Edition. (New York: Morehouse Publishing, 2014), 9. Also see Howard A. Snyder, Jesus and Pocahontas: Gospel, Mission, and National Myth (Cambridge: Lutterworth Press, 2015).

[6] Owanah Anderson, 400 Years: Anglican/Episcopal Mission among American Indians (Cincinnati: Forward Movement, 1997), 7.

[7] “This may have been because Bishop John King of London was a member of the first Council of the Virginia Company. William Laud was Bishop of London from 1628 until 1633. In 1632 Laud sent a suggestion to the Privy Council “for the purpose of extending conformity to the national church to the English subjects beyond the sea.” On Oct. 1, 1633, the Privy Council ordered with regard to the colonies that “. . . in all things concerning their church government they should be under the jurisdiction of the Lord Bishop of London.” In 1638, when Laud was Archbishop of Canterbury, he proposed sending a bishop to New England. Lord Thomas Culpeper became Governor of Virginia in 1679. His instructions permitted appointment to cures of only those clergy who had certificates of conformity from the Bishop of London. This was the first specific reference to the traditional jurisdiction of the Bishop of London over the colonies. The American Revolution ended any jurisdiction held by the Bishop of London over the former American colonies.” https://www.episcopalchurch.org/glossary/london-bishop-of/

[8] “In Virginia the vestry in effect became a self-perpetuating institution in which existing members appointed new members: an oligarchy of the most powerful families. Vestries had the right to choose and appoint their minister. They often maintained a very strict control over him by employing him on a yearly contract. All members of the colony were required to pay a tax for the maintenance of the church. Ministers themselves were paid in tobacco.” Kevin Ward, A History of Global Anglicanism, 48.

[9] J. Barney Hawkins, “The Episcopal Church in the United States of America” in The Wiley-Blackwell Companion to the Anglican Communion, ed. Ian S. Markham et. al (Wiley-Blackwell: Malden MA, 2013), 510.

[10] Ward, History, 48 – 49.

[11] “Trinity Church endowed King’s College (chartered in 1654) as New York’s answer to Harvard, Yale and Princeton: what was to become Columbia University.” Ward, History, 50.

[12] “Two-thirds of the fifty-five signatories of the 1776 Declaration of Independence were Anglicans, including General George Washington (the first president) and James Madison (the third).” Kevin Ward, A History of Global Anglicanism, 52.

[13] “The word protestant differentiated the church from the Roman Catholic Church and the word episcopal was the name for the seventeenth-century English church party that favored retention of the episcopacy.” Prichard, 114.

[14] Because of his loyalist persuasion, Seabury was imprisoned for a period in 1775 by Connecticut patriots and also served as a chaplain to the King’s American Regiment (119). As a British chaplain, Seabury had drawn maps for the British troops while still receiving a pension from Great Britain in 1786.

[15] The Primus Robert Kilgour, Bishop of Aberdeen, Arthur Petrie, Bishop of Ross and Moray, and John Skinner, Kilgour’s coadjutor ordained Seabury to the episcopate.

[16] Webber, Welcome, 9.

[17] In 1787, the Archbishop of Canterbury consecrated William White of Pennsylvania and Samuel Provoost of New York at Lambeth Palace. “The creation of an episcopacy which was not connected with the state was to be of great significance for the development of the Anglican communion as a whole.” Ward, 54.

[18] “An autonomous Episcopal Church in the United States had changed forever the meaning of ‘Anglican.’” John L. Kater, Ministry in the Anglican Tradition from Henry VIII to 1900 (Fortress Academic: Lanham MD, 2022), 113.

[19] J. Barney Hawkins IV emphasizes this when he writes, “In revising the prayer book, in electing bishops, as well as in its daily life, the Episcopal Church in the United States takes seriously the authority and voice of the laity. In 2003, this often-overlooked reality was put to the test for the Anglican Communion when the clergy and laity in New Hampshire elected a new bishop who was openly gay. Because the people of New Hampshire had spoken, many in the Episcopal Church’s House of Bishops and House of Deputies believed it was reasonable to consent to his consecration.” J. Barney Hawkins IV, “The Episcopal Church in the United States of America” in The Wiley-Blackwell Companion to the Anglican Communion, ed. Ian S. Markham et. al (Wiley-Blackwell: Malden MA, 2013), 514.

I dedicate these brief introductions to the Episcopal Church to Mary Ann Flanagan (1930 – 2023), a lovely woman who worshipped regularly at Christ Episcopal Church in Eureka CA. Her deep interest and curiosity about the history of The Episcopal Church (TEC) inspired us both to read A History of the Episcopal Church by Robert W. Prichard, a book that helped inform and inspire these three brief introductions: TEC (1579 – 1792), TEC (1792 – 1888), TEC (1888 – 2022).