Readings for the Nineteenth Sunday after Pentecost (Proper 24 – Year C – Track 1)

Jeremiah 31:27-34

Psalm 119:97-104

2 Timothy 3:14-4:5

Luke 18:1-8

This sermon was preached at Christ Episcopal Church in Eureka CA on October 16, 2022.

Over the last several weeks, I’ve been teaching a church history and spirituality class online for the Episcopal seminary in Berkeley called “Anglican Identity” in which the students and I have been engaging in the foundational spiritual discipline that ultimately forms one’s identity as an Episcopalian and Anglican: the practice of common prayer. We’ve been praying with the original 1549 Prayer Book, the poetry of George Herbert and John Donne, the beloved hymns of Charles Wesley, and the Centering Prayer method described in the Cloud of Unknowing. These tried-and-true prayers of our Anglican tradition have reminded me how valuable it is for us to be brutally honest in our personal and communal dialogues with the divine, unafraid to challenge and even argue with God, the way the poor widow challenges the judge in today’s parable. The great Anglican priest and poet George Herbert described prayer as the “Engine against th’ Almighty,” and as “Reversed Thunder,” and as the “Christ-side-piercing spear.” The medieval author of the Cloud of Unknowing also used the image of a spear that pierces heaven in reference to our prayers. In one of his poems titled “Artillery,” George Herbert speaks to God saying, “Thou dost deign to enter combat with us, and contest with thine own clay.” God seems willing and eager to wrestle through life with us and even to wrestle with us, as Jacob did with the angel (which happens to be an alternate Hebrew Scripture reading for this Sunday).

The evangelical Anglican Charles Wesley cried out vigorously and almost angrily to God in one of his most famous hymns titled “Jesus, Lover of my Soul.” One of the great American preachers Henry Ward Beecher said, “I would rather have written ‘Jesus, Lover of my Soul’ than to have the fame of all the kings that ever sat on earth.”[1] Unfortunately, most hymnals (including our own) omit the most moving verse in which Charles Wesley laments with brutal honesty and asks God, “Wilt thou not regard my call? / Wilt thou not accept my prayer? / Lo, I sink, I faint, I fall! / Lo, on thee I cast my care, / Reach out to me thy gracious hand! / Hoping against hope I stand.” The hymn is hymn 699 in our hymnal and you won’t find that verse included, most likely because it’s too painfully honest. Next time we sing that hymn here, I’ll suggest we put that verse back in, because those words capture so well the spirit of the poor widow in today’s parable, the poor widow who keeps appearing before the unjust judge, pleading for justice.

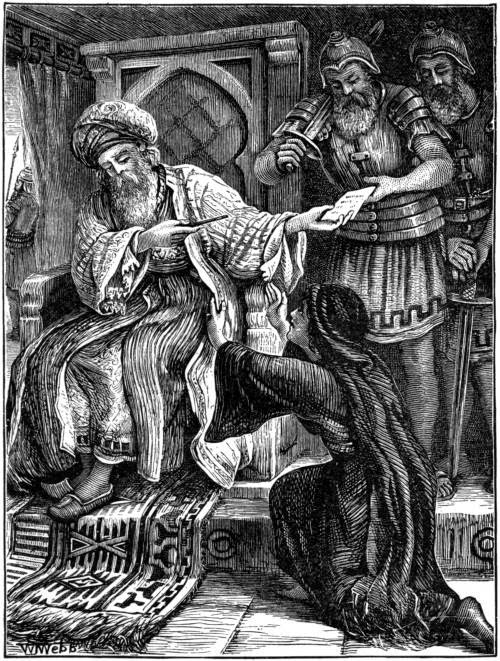

In this parable, Jesus employs a rabbinic form of teaching known as qal va’chomer which means “from less to more” or “from the minor to the major.” It’s a form of logical argument that claims that if the minor version of something has a particular property, then the major version must certainly and undoubtedly have that same property even more so. An example might be, if I have love and affection for my two yorkies and feel the need to hug them every time I see them, then how much more does God love my two yorkies whom he created? And how much more does God love me? Earlier in Luke’s Gospel, Jesus uses this qal va’chomer teaching technique when he asks, “Which of you fathers, if your son asks for a fish, will give him a snake instead? Or if he asks for an egg, will give him a scorpion? If you then, though you are evil, know how to give good gifts to your children, how much more [poso mallon] will your Father in heaven give to those who ask him!” (Luke 11:11 – 13). And Jesus loves to use unrighteous people in his parables in order to make this point. Remember the parable of the dishonest steward? Jesus said, “If the dishonest steward knew how to give away money generously, how much more should the children of light give generously to the church and to those in need?” (Luke 16:1-13). In today’s parable, Jesus says, “If this judge, who is unjust, grants the widow’s request, how much more will God, who is just and merciful, grant the requests of those who cry out to him day and night?”

Now this parable clearly teaches us to “be persistent” in our prayers, as Paul says (2 Timothy 4:2), to pray always and to not lose heart as the Gospel itself says at the beginning of the parable, but it’s saying more than that. Jesus says, “Listen to what the unjust judge says.” The judge says, “I will grant this widow justice so that she may not wear me out by continually coming.” The original Greek word for “wear me out” is hupopiatze, which is the same word used in boxing (ancient Greek boxing) for getting a black eye from a punch in the face. So, the widow’s persistence is so overwhelming that it feels to the judge like a physical punch in the face. This is describing the kind of vigorous, assertive, audacious, brave, and bold prayer that Jesus hopes to find among us. And yet, when the Son of Man comes, will he find this kind of faith on earth?

One of the commentaries I read said that “an elderly black minister read this parable and gave a one-sentence interpretation: ‘Until you have stood for years knocking at a locked door, your knuckles bleeding, you do not really know what prayer is.’”[2] Christ, who himself prayed so vigorously that he sweat drops of blood, is hoping to see in us the kind of prayer that is best described using the language of fist-fighting, boxing and wrestling, like Jacob wrestling with the angel. In this parable, Christ says to us, “Be brutally honest in your prayers,” like George Herbert and Charles Wesley. In this parable, Christ says to us, “Say whatever you need to say to God because he can handle it better than anyone else.” In this parable, Christ says to us in the words of a famous Eurekan who is in town today, “Say what you want to say. Let the words fall out honestly. I want to see you be brave…”

“…I want to see you be brave like the poor widow whose bold persistence made the unjust judge feel like he got punched in the face.” God can handle it. In fact, the God who, according to George Herbert “dost deign to enter combat with us, and contest with [his] own clay,” almost seems to prefer our prayers to have an honest punch to them.

Sometimes we might feel like God is behaving like an unjust judge and it’s ok to be honest about that with God. It’s ok to be annoyed and angry at God, not for the sake of being angry, but for the sake of honest relationship and for the sake of truth and justice, while also acknowledging the mystery of God’s ways. This parable also shows that the human experience seems to be one of delay. When we pray vigorously night and day in times of long delay we are being formed “into a vessel that will be able to hold the answer when it comes” and it will come.[3] In the meantime, will the Son of Man find faith on earth? Will Christ find in us the persistent and brave prayers that have the same punch as the poor widow?

[1] Robert McCutchan, Our Hymnody, 338, as cited in S. T. Kimbrough, Jr. Wrestling the Angel: Charles Wesley Struggles with Vital Questions of Faith (Resource Publications: Eugene OR, 2022), 96.

[2] Fred B. Craddock, Luke (John Knox Press: Louisville KY, 1990), 210.

[3] “It remains the unavoidable truth that [the story presents] prayer as continual and persistent, hurling its petitions against long periods of silence. The human experience is one of delay and honestly says as much, even while acknowledging the mystery of God’s ways. Is the petitioner being hammered through long days and nights of prayer into a vessel that will be able to hold the answer when it comes? We do not know. All we know in the life of prayer is asking, seeking, knocking, and waiting, trust sometimes fainting, sometimes growing angry.” Fred B. Craddock, Luke (John Knox Press: Louisville KY, 1990), 209 – 210.