A brief introduction to The Anglican Church in Aotearoa, New Zealand and Polynesia for the Anglican Cycle of Prayer

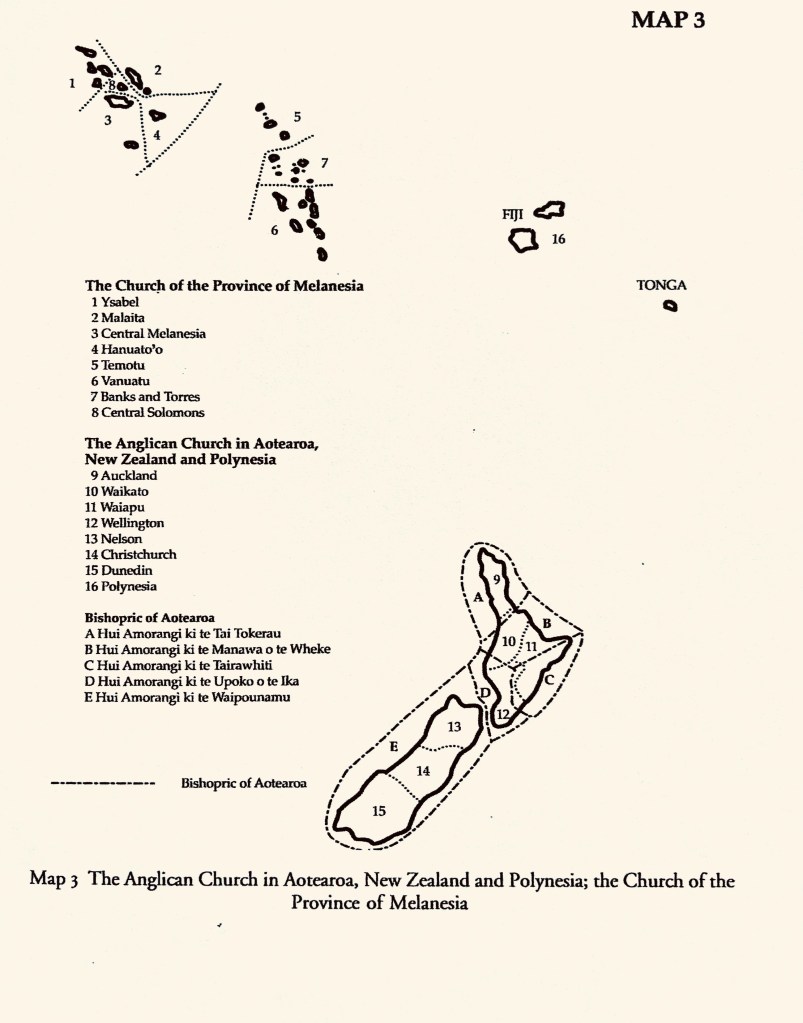

In the Anglican Cycle of Prayer, we pray for the Anglican Church in Aotearoa, New Zealand, and Polynesia, which is a church consisting of three cultural streams (tikanga): Māori (the indigenous peoples of New Zealand), Pākehā (New Zealanders of European descent) and Polynesian.[1]

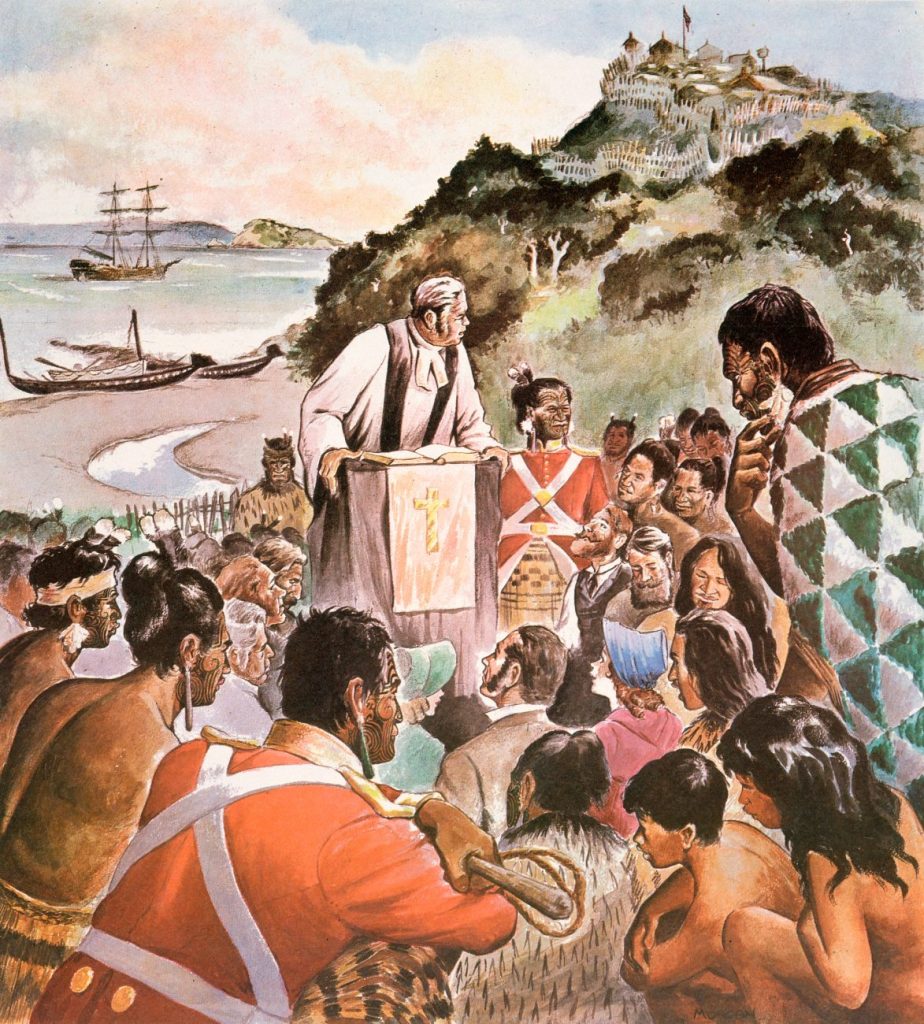

In 1809, an Anglican chaplain in Australia named Samuel Marsden met a young Māori sailor named Ruatara and, after meeting other Māori[2] at Parramatta in Australia, became convinced that they were “a very superior people in point of mental capacity.”[3] Marsden urged the Church Missionary Society (CMS) to establish a mission in New Zealand; and on Christmas Day in 1814, he led the first Christian service in Aotearoa, preaching to an assembled crowd while Ruatara translated. The Rev. Samuel Marsden later became known as the “Apostle to New Zealand.”

Soon other missionaries followed, including Thomas Kendall and Henry Williams, who began to put the Māori language into written form.[4] By the late 1830s, a substantial Christian community had arisen under the patronage of Māori chiefs.[5] As Europeans continued to settle the island country, the CMS urged the British government not to colonize the region in a way that would repeat many of the problems associated with previous colonial enterprises. The CMS, however, also advised the Māori to request some kind of British rule and protection in order to both prevent other European powers from colonizing the region (such as the Catholic French) and to control white settlement. The CMS proved instrumental in securing an agreement between Māori chiefs and the British in the Treaty of Waitangi of 1840.[6] The Treaty of Waitangi became a symbol of redemption and protest to colonial oppression.[7]

In 1841, George Augustus Selwyn was consecrated at Lambeth as the Bishop of New Zealand at age 32.[8] Although he was a high churchman and therefore not the first choice of CMS, the missionary society nevertheless supported him. Selwyn mastered the Māori language and was able to preach in it upon his arrival. He consistently protested against infringements of the Treaty of Waitangi, especially when the British and the Māori fought over land during skirmishes called the New Zealand Wars (1845 – 1872). Bishop Selwyn was able to minister to both sides, and to keep the affection and admiration of both natives and colonists.[9] In 1853, Bishop Selwyn ordained the first Māori deacon, Rota (Lot) Waitoa, but he delayed in priesting him because he felt that more education was required.[10] Selwyn founded the College of St. John the Evangelist in Auckland, named after his alma mater, St. John’s College in Cambridge.[11]

In 1857, Bishop Selwyn laid down a constitution for the church, influenced by The Episcopal Church’s polity.[12] Selwyn advocated for a synodical government of three houses: bishops, clergy, and laity with consent in each house being necessary for legislation to pass.

Although the number of Māori clergy slowly increased, no Māori bishop was appointed until 1928 when Frederick Augustus Bennett became a suffragan bishop. Bishop Bennett was given the title “Bishop of Aotearoa,” but he remained limited by ecclesiastical restrictions. In the 1970s and 1980s, young Māori engaged in political protests over land rights, justice issues, institutional racism, police brutality, educational injustice, and poor housing conditions. “Maori,” Jenny Ta Paa-Daniel writes, “were and have remained at the forefront of emergent international indigenous protest groups.”[13]

After a proposal for a Māori diocese was rejected by the Māori Anglicans who did not want to be represented by a Pakeha, they chose to affirm New Zealand as a bicultural society and to reshape the church as a family of three tikanga (cultural streams): Māori, Pakeha, and Polynesian.

The seven dioceses of New Zealand form Tikanga Pākehā. The former bishopric of Aotearoa has undergone transformation into five regions known as Hui Amorangi, each with a bishop. The Diocese of Polynesia, with its vast distances and nine languages, forms the third part of the rearrangement.[14]

The first female priest in New Zealand, the Rev. Puti Murray, was ordained in 1978; and in 1990, the church consecrated the first female diocesan bishop of the Anglican Communion: the Rt. Rev. Penelope Jamieson.[15] There is a wide divergence of attitudes towards LGBTQ people in the church and this varies in accordance with cultural norms and how Scripture is interpreted.[16]

In 1989, the church published A New Zealand Prayer Book – He Karakia Mihinare o Aotearoa, which has proven to be a valuable liturgical resource for the entire Anglican Communion and beyond. The liturgies are composed in both Māori and English and one of the Eucharistic liturgies, composed by Māori scholars, used proverbial allusions from Māori poetry and oratory. Along with the pacifying Night Prayer,[17] the New Zealand adaptation of the Lord’s Prayer is an especially poetic offering that is worth praying often:

Eternal Spirit,

Earth-maker, Pain-bearer, Life-giver,

Source of all that is and that shall be,

Father and Mother of us all,

Loving God, in whom is heaven:

The hallowing of your name echo through the universe!

The way of your justice be followed by the peoples of the world!

Your heavenly will be done by all created beings!

Your commonwealth of peace and freedom sustain our hope and come on earth.

With the bread we need for today, feed us.

In the hurts we absorb from one another, forgive us.

In times of temptation and test, strengthen us.

From trials too great to endure, spare us.

From the grip of all that is evil, free us.

For you reign in the glory of the power that is love,

now and forever. Amen.[18]

[1] “Aotearoa is the name commonly used by Maori and increasingly by non-Maori New Zealanders, to describe the country renamed after the 1642 visit of Dutch voyager Abel Janzoon Tasman, who wrote the name Staten Landt in his original journal records of his encounter with Maori people. Later historians abstracted the name Nouvelle Zelande from others of Tasman’s journals.” Jenny Ta Paa-Daniel, “Leadership,” 290, n. 2.

[2] “The Maori are a people of Polynesian origin who first came to Aotearoa (The Land of the Long White Cloud) some 1,000 years before the arrival of the Pakeha (whites), who first came as whalers and traders in the late eighteenth century.” Kevin Ward, A History of Global Anglicanism (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 286. Also see G. W. Rice (ed.), The Oxford History of New Zealand (Auckland: Oxford University Press, 1992).

[3] Yarwood, A. T., Samuel Marsden: The Great Survivor (Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 1977), 74 – 75.

[4] Jenny Te Paa-Daniel wrote, “It was not until 1823, when ex-naval captain Henry Williams arrived from England, that there is any real evidence of Maori ‘conversion’ to Christianity. However, once begun, Maori adherence to Christian faith teachings and practices was enthusiastic and unstoppable.” Jenny Plane Te Paa, “Leadership Formation for a New World: An Emergent Indigenous Anglican Theological College” in Beyond Colonial Anglicanism: The Anglican Communion in the Twenty-First Century (New York: Church Publishing Inc, 2001), 275.

[5] “By one reckoning some 43,000 people attended Anglican churches out of an estimated total Māori population of 110,000 [by 1840].” Ward, History, 287.

[6] “The Treaty of Waitangi, albeit a political mechanism, thus envisaged a partnership relationship between indigenous Maori and Pakeha settlers—an opportunity for modeling the possibilities of bicultural development within one nation.” Jenny Ta Paa-Daniel, “Leadership,” 276.

[7] “The ‘icon’ or symbolic focus of protest in Aotearoa New Zealand has always been the Treaty of Waitangi, the original covenant document which recognized the right of Maori as a sovereign people, to ‘treat’ honorably with another sovereign people for the terms essential to a future which envisaged peaceful and settled co-existence as co-equal partners in one land.” Jenny Te Paa-Daniel, “Leadership,” 279.

[8] Speaking of Lambeth, Bishop Selwyn was one of the bishops “who worked to inaugurate the first Lambeth Conference in 1867, and was actively engaged in working to continue the Lambeth relationship until his death. He laid the foundations for the second Lambeth Conference and thereby the ongoing life of the Anglican Communion.” Christopher Honoré, “The Anglican Church in Aotearoa, New Zealand, and Polynesia” (374 – 386) in The Wiley-Blackwell Companion to the Anglican Communion, ed Ian S, Markham et al (Malden MA: John Wiley & Sons, 2013), 385.

[9] Jenny Te Paa-Daniel offers a different perspective on Bishop Selwyn’s ministry: “A complex of factors, not the least of which were simply lousy timing, inevitable tensions between the CMS evangelicals and Selwyn’s high churchmanship, and his unfortunate colonial associations, mitigated against Selwyn’s ministry efforts among the CMS and Maori. He was never to enjoy the depth of trusting relationships, like those that existed between CMS missionaries and Maori.” Jenny Te Paa-Daniel, “Leadership,” 276 – 277.

[10] This delay in promoting Māori clergy may have fueled the discontent which produced the King movement, a movement that attempted to syncretize Christianity with traditional Māori spirituality. Ward, History, 289.

[11] “In 1992, the College of St. John the Evangelist was transformed into two distinctive societies or Colleges, one representing the autonomous interests of Maori Anglicans and the other Pakeha Anglicans, and yet each is committed to a functional partnership relationship.” Jenny Te Paa-Daniel, “Leadership,” 284. Jenny Te Paa-Daniel is Ahorangi or Dean of Te Rau Kahikatea, indigenous constituent of the College of St. John the Evangelist in Auckland, New Zealand. She was the first Māori person to complete an academic degree in theology. She earned her PhD at the Graduate Theological Union in Berkeley CA.

[12] “By this time, many Māori had experienced ‘being Anglican’ for nearly forty years, and yet not one Māori signature was attached to the first Constitution.” Jenny Te Paa-Daniel, “Leadership,” 277.

[13] Jenny Te Paa-Daniel, “Leadership,” 279.

[14] Honoré, 378.

[15] Bishop Jamieson was elected to the See of Dunedin in 1990 and served until her retirement in 2004. Although Bishop Barbara Harris of the Diocese of Massachusetts in TEC was the first female bishop of the Anglican Communion, she was a suffragan bishop while Bishop Jamieson was a diocesan bishop.

[16] Honoré, 382.

[17] A New Zealand Prayer Book – He Karakia Mihinare o Aotearoa, 184.

[18] A New Zealand Prayer Book – He Karakia Mihinare o Aotearoa, 181.

Fun Fact:

On April 11, 2018, the Episcopal Church Women of Christ Episcopal Church Eureka observed the Feast Day of Bishop George Augustus Selwyn by celebrating Eucharist using the New Zealand Prayer Book