A brief introduction to The Church in Wales for the Anglican Cycle of Prayer

In his poem titled “In Church,” Welsh poet and priest R. S. Thomas writes,

Often I try

To analyze the quality

Of its silences. Is this where God hides

From my searching? I have stopped to listen,

After the few people have gone,

To the air recomposing itself

For vigil. It has waited like this

Since the stones grouped themselves about it.

These are the hard ribs

Of a body that our prayers have failed

To animate. Shadows advance

From their corners to take possession

Of places the light held

For an hour. The bats resume

Their business. The uneasiness of the pews

Ceases. There is no other sound

In the darkness but the sound of a man

Breathing, testing his faith

On emptiness, nailing his questions

One by one to an untenanted cross.

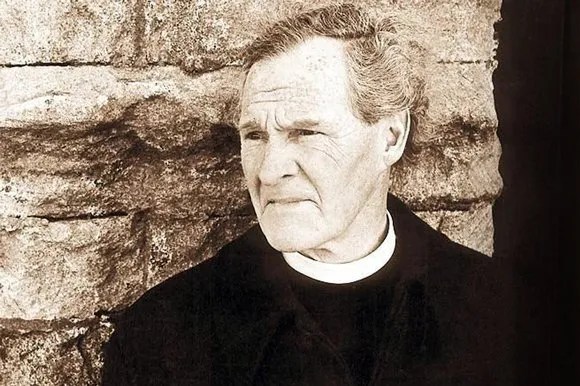

In the Anglican Cycle of Prayer, we pray for the church in which this distinguished poet R. S. Thomas served, the Church in Wales. There is evidence of Christianity existing in Wales centuries before the arrival of St. Augustine of Canterbury in 597. Roman soldiers Julius and Aaron of Caerleon were martyred in the early third century, likely during the persecution of Christians led by Septimius Severus, the same persecution responsible for the martyrdom of St. Alban.[1] The ancient Christians of Wales were part of the Celtic stream of Christianity which thrived in Ireland and Scotland and came to a head with Roman Christianity at the Synod of Whitby in 664. The Celtic Christians of Wales were deeply influenced by the Desert spirituality of Egypt and Palestine which came to Britain via Gaul through the writings of John Cassian. Tribal communities and kingdoms formed into dioceses and monastic communities which focused on scholarship, prayer, and mission. One of the early missionaries was St. David, the patron saint of Wales (d. March 1, 589 CE). The mother churches at the center of these territories gave the regions their name, which is why so many Welsh places begin with the prefix “Llan,” which means “church,” followed by the name of its founder.[2]

[After the Norman Conquest (1066), the four ancient dioceses in Wales (St. Davids, St. Asaph, Bangor, and Llandaff) became part of the province of Canterbury and bishops were appointed by the Crown. During this time, Celtic practices such as the possibility of marriage for clergy were forbidden and Welsh religious houses were replaced by Benedictine and Cistercian monasteries.[3]]

During the English Reformation, the monasteries were dissolved and although Henry VIII’s Act of Union (in 1536) deprived the Welsh language of its official status, the Book of Common Prayer and the entire Bible were translated and published into Welsh in 1567 and 1588, respectively, thus saving the language from extinction.[4]

[In 1920, the Church of England was disestablished within Wales and the four Welsh dioceses formed into an independent province within the Anglican communion, electing its own bishops and archbishop. The name “The Church in Wales” was chosen over “The Church of Wales” in deference to Nonconformists and to emphasize its mission to all people living in Wales.[5]] From the 1950s onward, the church became much more than the Church of England in Wales and began to assume a leading role as the guardian of the use of the Welsh language in worship. The Church in Wales is a bilingual church, offering services in both English and Welsh.

As the church faces significant decline in membership,[6] former Archbishop Barry Morgan says, “The Church is often prepared to think radically, but it is reluctant to implement consequent recommendations.[7] … And when the church takes decisive actions, it can fail to follow them through to their logical conclusions. Wales was one of the first provinces to ordain women to the diaconate, in 1980, but it was not until 1997 that the canon to ordain them priests was passed, having failed in 1994, and so Wales was the last Anglican province in the British Isles to ordain [women to the priesthood].”[8] Also, an attempt to open the episcopate to women priests was defeated in 2008. However, in September 2019, the Rev. Cherry Vann was elected the Bishop of Monmouth and she lives with her civil partner, Wendy.

“The challenge,” Barry Morgan writes, “is to see tradition as a dynamic process, embracing creative innovation and challenging members to new ways of thinking for the sake of the gospel[9]…[and yet] compared with the problems faced by many provinces of the Anglican Communion, those of the Province of Wales fade into insignificance. Anglican churches in many parts of the world face persecution, civil unrest, famine, natural disasters, poverty, and war. The Church in Wales, ought, therefore, to be a church that counts its blessings. Its history also ought to give it a sense of perspective and confidence to resolve successfully the issues which it faces as its leaders and members did in earlier times.”[10]

Morgan would likely encourage the Church in Wales to emulate the Welsh priest R. S. Thomas[11] and to “analyze the quality of its silences,” to stop and listen to the God whose presence in the darkness and in a solitary person’s breath may be part of the answer to the nagging questions we nail to the Cross.

Fun fact

- The first Archbishop of Canterbury to come from a province outside of the Church of England (since the Reformation) came from the Church in Wales: Rowan Williams who served as Archbishop of Canterbury from 2002 to 2012.

[1] Also, there is record of three British bishops being present at the Council of Arles in France in 314 CE

[2] Barry Morgan, “The Church in Wales” in The Wiley-Blackwell Companion to the Anglican Communion, 453. For example, Llandeilo, Llanilltud, Llanbadarn, and Llandaff.

[3] Morgan, “The Church in Wales,” 453.

[4] “The Anglican Church,” according to Kevin Ward, “was as important in the process [of preserving the Welsh language and culture] as it was to be among the Yoruba or Baganda in nineteenth-century Africa.” Kevin Ward, A History of Global Anglicanism, 24. The Rev. Dr. John Kater taught me the importance of Article 34 in the 39 Articles which reads: “It is not necessary that Traditions and Ceremonies be in all places one, or utterly like; for at all times they have been divers, and may be changed according to the diversity of countries, times, and manners, so that nothing be ordained against God’s Word….so that all things be done to edifying.” He taught me that this article captures, in many ways, the unique charism of Anglicanism, which at its best does not emphasize the English language in worship, but the vernacular language in worship.

[5] Kevin Ward, A History of Global Anglicanism, 25.

[6] The Church in Wales remains the largest denomination in Wales, but average Sunday attendance is around 35,500 among a population of over 3 million.

[7] Morgan writes, “In the 1970s, a commission recommended the re-organization of diocesan boundaries, but this failed to win approval at the Governing Body in 1980.” Morgan, 461.

[8] Morgan, 461.

[9] Some examples of creative innovation include collaborative interfaith work with the Muslim Council of Wales, the promotion of eco-justice and green projects within dioceses by CHASE (Church Action on Sustaining the Environment), and the recovery of the ancient Celtic spiritual tradition in Welsh liturgy.

[10] Morgan, “The Church in Wales,” 462.

[11] R. S. Thomas is considered one of the three greatest poets of the English language in the 20th century, along with William Butler Yeats and T. S. Eliot.