Readings for the Fifth Sunday after Pentecost (Proper 10 – Year C – Track 1)

This sermon was preached at Christ Episcopal Church in Eureka CA on July 10, 2022.

This summer, we have been on a global odyssey through the Anglican Communion as we have been learning about the many provinces for which we pray each Sunday in our Anglican Cycle of Prayer.[1] Today, along with millions of Anglicans around the world, we pray for the Church of the Province of Uganda, which is the largest province in the Anglican Communion after the Church of England, composed of over 10 million Anglican Christians.[2] I recently learned that perhaps the most beloved Anglican bishop in Uganda used to be a regular speaker at my alma mater, Westmont College in Santa Barbara![3] Bishop Festo Kivengere, who served as the Bishop of Kigezi in southwest Uganda, was such a popular preacher and evangelist that he became known as the “Billy Graham of Africa” and his life and ministry exemplify key teachings in this morning’s Scripture readings.

Much like Amos, who rose from his life as a lowly shepherd and fig tree farmer to become a great Hebrew prophet boldly confronting and condemning Israel’s corrupt king Jeroboam II, Festo Kivengere also grew up as a cattle-herder[4] before becoming a prophetic bishop boldly condemning the tyrannical behavior of Ugandan dictator Idi Amin, who has been called the “Hitler of Africa.” Like the prophet Amos, Festo knew that violence and gross injustice indicated corruption and crookedness of heart just as a plumb line indicates the crookedness of a wall (Amos 7:7). As a result of his outspoken condemnation of Idi Amin, Festo Kivengere was put on the top of the dictator’s hit list, right below the Archbishop of Uganda Janani Luwum whom Idi Amin had had murdered (and then tried to cover up by claiming he died in a car accident).

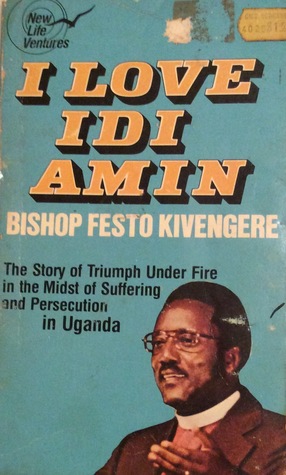

Even though Idi Amin’s heart was as crooked as King Jeroboam’s (if not more) and was hellbent on murdering Festo Kivengere, the bishop responded with love and forgiveness, inspired by Christ’s teaching to love our enemies as well as Christ’s radical words of compassion on the Cross, “Father, forgive them for they know not what they do.” After fleeing Uganda with his wife and safely arriving in Rwanda and eventually England, Kivengere authored a book with the provocative and controversial title I Love Idi Amin.[5]

Bishop Festo Kivengere’s heart had been flooded with God’s love just as Paul had prayed that the Christians in Colossae would be filled with the knowledge of God’s will (Colossians 1:9). This divine love and compassion infiltrated Festo’s innermost parts in the same way that compassion infiltrated the heart of the Good Samaritan, who was, according to the parable, “moved with pity,” a phrase that is a translation of one Greek word esplagchnisthe, which includes the word splanxna, meaning “the gut” or “the entrails.” The Samaritan was moved viscerally in his gut by the sight of this broken man on the side of the road. Similarly, Bishop Festo was moved with compassion for the dictator who wanted him dead. Festo forgave Idi Amin and prayed for him because he knew the dictator was also a broken man, trapped in “a terrible spiritual prison.”[6]

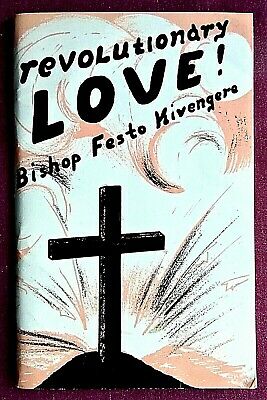

Bishop Festo loved preaching about the love of Christ that floods our hearts and our innermost parts (Romans 5:5)[7] because it is this revolutionary love[8] that brought peace and harmony to warring tribes in Africa. In one of his addresses at Westmont College, Festo used the example of Burundi where there had been, in his own words, “a terrible, sick confusion of hatred, not racial, not racial, but tribal.” He said, “In Burundi, they speak one language and they’re all black and yet what happened? One tribe looked at the other and hatred came in and it became sicker and sicker…in this terrible conflict of hate, 15,000 lives had died; men, women, and little children.”[9] Now before we judge the Burundians who were deeply divided while sharing a common language and race, let’s acknowledge our own profound divisions among ourselves, among citizens of this country, among Christians, among Anglicans, among Episcopalians. Sometimes it is those with whom we have the most in common that we are tempted to hate the most. (There are some disagreements and debates being hashed out among 1,200 Episcopalians today at General Convention in Baltimore and we pray the debates are civil and productive).

Bishop Festo loved preaching about the love of Christ that floods our hearts and that can bring together tribes and peoples who avoid and even detest one another, not unlike the Jews and the Samaritans. When Jesus makes a Samaritan the hero of his parable, he’s not just throwing a curve ball, he is scandalizing his first-century Jewish listeners. The Samaritan was the “detestable other,” the one from whom we believe nothing good could ever come. Now who might that be for you? Whoever that is, replace the Samaritan in the parable with that person and then you’ll get an idea of how scandalizing this parable was for the first-century listeners and readers. Let that challenge you and disturb you and crack open your heart so that the love of Christ may flood through every crevice in your innermost parts. Let the revolutionary love of Christ which inspired Bishop Festo Kivengere to say “I love Idi Amin” flow through you. To borrow the poetic words of that other herdsman-turned-prophet Amos, let Christ’s love flow through you like a mighty river and like an ever-flowing stream. Amen.

[1] The term “global odyssey” is a nod to the Rev. Canon Howard Albert Johnson who wrote Global Odyssey: An Episcopalian’s encounter with the Anglican Communion in eighty countries (Harper & Row, 1963).

[2] Learn more about the Church of the Province of Uganda here: https://deforestlondon.wordpress.com/2022/07/08/the-church-of-the-province-of-uganda/

[3] He also preached at the foot of Mount Kilimanjaro, which Doug Moorehead has hiked.

[4] “We were a cattle people. To my tribe, cows were what made life worth living. By the time I was three, I knew the name of every one of my father’s 120 cows, bulls, and calves. Some men I knew thought more of their cattle than of their children.” Festo Kivengere with Dorothy Smoker, Revolutionary Love (Moscow ID: Community Christian Ministries, 1983),6.

[5] Festo Kivengere with Dorothy Smoker, I Love Idi Amin: The Story of Triumph under Fire in the Midst of Suffering and Persecution in Uganda (Old Tappan NY: Fleming Revell, 1977). Kivengere writes, “Many have argued with me about the title of my little book I Love Idi Amin. And I can only go back to that first Good Friday after our escape from Uganda. We were in England and the newspapers were reporting daily the increased persecution back home. The six young actors who were to have represented the early martyrs of Uganda in a play for the church’s Centennial Celebration were found dead together in a field. And on and on. With the pain we had already gone through, I felt something was strangling me spiritually. I grew increasingly bitter toward Amin, and was, to the same degree losing my liberty and my ministry. I slipped into the back of All Souls Church in London [Langham Place] to listen to the meditations on the seven last words of Christ on the cross. The first word was read distinctly: ‘Father, forgive them; for they do not know what they are doing’ (Luke 23:34, NASB). So said my Lord when the cruel nails were being driven into His hands. His amazing love pressed into my consciousness. To me he was saying, ‘You can’t forgive Amin?’ ‘No, Lord.’ ‘Suppose he had been one of those soldiers driving the nails into my hands. He could have been, you know.’ ‘Yes, Lord, he could.’ ‘Do you think I would have prayed, “Father, forgive them, all except that Idi Amin?” I shook my head. ‘No, Master. Even he would have come within the embrace of Your boundless love.’ I bowed, asking forgiveness. And, although I frequently had to repent and pray again for forgiveness, I rose that day with a liberated heart and have been able to share Calvary love in freedom. Yes, because of His immeasurable grace to me, I do love Idi Amin, have forgiven him, and am still praying for him to escape the terrible spiritual prison he is in.” Kivengere, Revolutionay Love, 96 – 97.

[6] Festo Kivengere with Dorothy Smoker, Revolutionary Love (Moscow ID: Community Christian Ministries, 1983),97.

[7] Paraphrasing Romans 5:5, Kivengere says, “For we are no longer in despair. We have received the kind of hope which shall never let us down. Why? For the love of God has flooded our hearts by the Holy Spirit whom God has given to us as a gift…flooded…flooded with love.” Bishop Festo Kivengere speaking at Westmont College, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M9i-cAixe-8, 25:30.

[8] Revolutionary Love is the title of Kivenge’s memoir in which he writes, “It is Christ’s revolutionary love that Africa desperately needs to bring radically new relationships between clans, tribes, nations, races, political parties and ideologies. It alone can cure economic exploitation, rampant corruption, unjust laws and hostility between religious denominations.” Kivengere, Revolutionary Love, x.

[9] Bishop Festo Kivengere speaking at Westmont College, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M9i-cAixe-8, 18:50.