A brief introduction to The Church of the Province of Uganda for the Anglican Cycle of Prayer

In the Anglican Cycle of Prayer, we pray for the Church of the Province of Uganda, which includes over ten million Anglican Christians. In fact, today one out of every nine Anglicans is a Ugandan.[1] According to the former Anglican Archbishop of Uganda Henry Luke Orombi, the church is built upon the following three pillars: martyrs, revival, and the historic episcopate.[2]

Martyrs

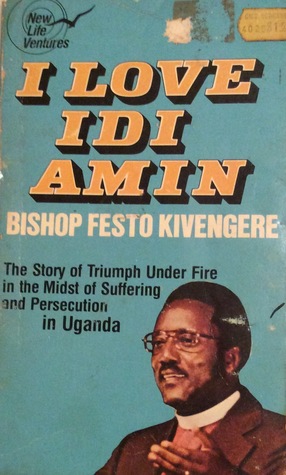

On October 29, 1885, Bishop James Hannington said, “Tell the Kabaka that I die for Uganda” moments before being martyred by order of the King (Kabaka) of BugandaMwanga II.[3] Less than a year later, on June 3, 1886, the same Kabaka initiated a persecution of Baganda Christians, mainly young pages, but also some older men. After refusing to recant Christ, Archbishop Orombi writes, “They cut and carried the reeds that were then wrapped around them and set on fire in an execution pit. As the flames engulfed them, these young martyrs sang songs of praise.”[4] Hundreds of Catholics and Protestants died for their faith and about sixty at the execution site of Namugongo, where there is now a Catholic shrine commemorating the martyrs.[5] In 1977, the archbishop of the province, Janani Luwum, publicly condemned the tyrannical behavior of Ugandan dictator Idi Amin, who responded by murdering Luwum and then falsely claiming that he died in a car accident. Before dying as a martyr, Luwum told Bishop Festo Kivengere, “They are going to kill me. I am not afraid.” When Bishop Festo Kivengere learned that he was next on the hitlist to be killed by Idi Amin, he fled to Rwanda on the insistence of his friends who said, “One bishop’s death this week is enough for us.”[6] However, Festo responded to Idi Amin’s violent rage with love and forgiveness, even authoring a book titled I Love Idi Amin.[7]

Revival

Festo Kivengere was the Bishop of Kigezi (in southwest Uganda) and a renowned leader of the East Africa Revival, which he initially dismissed as “sheer fanaticism.”[8] After a direct encounter with Christ, who appeared to him with arms outstretched on the Cross saying, “This is how much I love you,” Festo gave his life over to the revolutionary power of God’s love and eventually became known as “the Billy Graham of Africa.”[9] Kivengere served as an influential catalyst for the already burgeoning East Africa Revival which was initially sparked by the friendship and ministry of Evangelical missionary Dr. Joe Church (from the Church Missionary Society) and Bugandan leader Simeoni Nsibambi at a mission hospital in Gahini, Rwanda in the 1930s.[10] The Revival transformed a nominally Anglican church in Uganda into a vibrant community of enthusiastic believers who each had their own personal relationship with Christ and their own testimony about how Christ changed their lives. Many trace the tremendous growth of the Anglican Church to the success of the East Africa Revival.[11] Although gifted preachers and evangelists like Festo Kivengere contributed to the success of the revival, Kivengere himself explained, “Ordinary folk, bound together in a true love-fellowship, can be a powerhouse for evangelism.” Such small groups led many in Uganda and East Africa to echo the words of the pagan Romans which North African theologian Tertullian tells us about, “Behold these Christians, how they love one another!”[12]

Historic Episcopate

The Anglican Church of the Province of Uganda was founded by evangelical missionaries of the Church Missionary Society and has remained deeply evangelical in its piety and expression, sharing much in common with other evangelical churches. However, one important characteristic that sets the church apart from other evangelical communities is the historic episcopate, which Ugandan Anglicans understand as a powerful symbol of their unbroken line of succession to the original twelve apostles. Through their bishops, all Anglican Christians are connected to the apostles and are therefore called to be “apostolic in nature: faithful to the apostolic message, [submissive] to apostolic authority in Scripture, committed to apostolic mission and ministry, devoted to apostolic worship.”[13] The first bishop of Uganda Bishop Alfred Robert Tucker embodied this apostolic nature effectively, especially with his emphasis on education.[14] He helped form Uganda’s first theological college, which was named after him in 1914, the year he died. In 1997, Bishop Tucker Theological College became Uganda Christian University, which now includes The Bishop Tucker School of Divinity and Theology.

Scripture as Common Thread

The common thread that runs through the three pillars of the Anglican church of Uganda (martyrs, revival, and the historic episcopate) is, according to Orombi, a deep commitment to the authority of the Bible. “For most families in the rural areas,” Griphus Gakuru writes, “the Bible is the only book on the shelf. Its presence in every Anglican’s home and the absence of other literature makes it the most read book. Many homes read some portion once or twice a day.”[15] The strongly evangelical approach to the Bible and hermeneutics has put the Church of Uganda at odds with western provinces of the communion (especially TEC), which tend to practice a more nuanced approach to Scripture, particularly around the issues of human sexuality.

Fun Facts

- Bishop Festo Kivengere used to speak regularly at Fr. Daniel’s alma mater Westmont College. However, Fr. Daniel never heard him live since Bishop Festo passed away before he graduated high school. You can listen to one of Bishop Festo’s addresses here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M9i-cAixe-8

- In his book Awakening the Quieter Virtues, Westmont Professor of Communications Greg Spencer wrote, “Years ago, I heard that the great Ugandan bishop Festo Kivengere said that one of the marks of followers of Jesus is that they laugh easily.”[16]

[1] Richard H. Schmidt, Glorious Companions: Five Centuries of Anglican Spirituality (Grand Rapids MI: William B. Eerdmans, 2002), 311.

[2] Archbishop Henry Luke Orombi, What is Anglicanism? August 2007 https://www.firstthings.com/article/2007/08/001-what-is-anglicanism

[3] Unbeknownst to Bishop Hannington, King Mwanga II held the belief that an enemy would arrive from the east.

[4] Kevin Ward explains that Mwanga’s “overall motivation was the need to act decisively to maintain his authority at a time of international crisis. The issue of the refusal by a young page to submit to Mwanga’s homosexual demands was one of the triggers, but by no means the most important” (Ward, 167). Orombi says they were killed “because they refused his homosexual advances and would not recant their belief in King Jesus.”

[5] Roman Catholics observe the Feast Day of Ugandan Martyrs on June 3.

[6] Festo Kivengere writes, “We had returned to our home in Kabale on Saturday at the urgent request of many in Kampala. Several high-level persons had reported that I was now at the head of Amin’s death list. When we reached home, we were told that Amin’s men had been there three times that day looking for me. Our brothers and sisters would not even let us pack or unpack anything, but urged us to flee as we were across the border that night. ‘One bishop’s death this week is enough for us,’ they said.” Festo Kivengere with Dorothy Smoker, Revolutionary Love (Moscow, Idaho: Community Christian Ministries, 1983), 94.

[7] Festo Kivengere with Dorothy Smoker, I Love Idi Amin: The Story of Triumph under Fire in the Midst of Suffering and Persecution in Uganda (Ada, Michigan: Fleming Revell, 1977).

[8] Kivengere, Revolutionary Love, 1.

[9] Kivengere writes, “When I reached my room, I knelt by my bed, struggling for words to the One in whom I no longer believed. Finally I cried, ‘God! If you happen to be there, as my friend says, I am miserable. If You can do anything for me, then please do it now. If I’m not too far gone….HELP!’ Then what happened in that room! Heaven opened, and in front of me was Jesus. He was there real and crucified for me. His broken body was hanging on the cross, and suddenly I knew that it was my badness that did this to the King of Life. It shook me. In tears, I thought I was going to Hell. If He had said, ‘Go!’ I would not have complained. Somehow I thought that would be His duty, as all the wretchedness of my life came out. But then I saw His eyes of infinite love which were looking into mine. Could it be He who was clearly saying, ‘This is how much I love you, Festo!’” Kivengere, Revolutionary Love, 10-11.

[10] Kivengere describes the origin of the East Africa Revival in this way: “The moving of the Holy Spirit in East Africa, of which I became a part in 1940, began ten years earlier. At first there were just two: Simeoni Nsibambi and Dr. Joe Church. They found each other by God’s ‘accident’ near Kampala, Uganda, when both were spiritually hungry to desperation. They dropped everything and sat together under a tree on Namirembe Hill studying the New Testament for days to find out more about the Holy Spirit. He found them, and led them to the cross of Christ and to a simple way of accepting its power daily for continuous personal reviving. They caught fire.” Kivengere, Revolutionary Love, 73. Several years later, Kivengere describes a Sunday morning worship service when the revival began to catch fire across East Africa: “On an ordinary Sunday morning a layman stood to read the regularly set Scripture lesson for the day in an ordinary Anglican church. As he was reading, people began to weep. Young people, old men and leading members of the church were affected. The designated preacher never had a chance to preach that day. Tears kept flowing as people saw their sins. When he finished, the man who was reading broke down too. An hour or so later, most of those still in the church—some had gone home—were on their feet singing. People were embracing after asking each other for forgiveness. Others were still kneeling. The following Sunday the congregation was doubled and the building was too small, so they met outside under the trees.” Kivengere, Revolutionary Love, 74 – 75.

[11] The growth of the Anglican Church in Uganda may also be related to the church’s association with the elite of Ugandan society and the people’s desire to participate in the elite. “It has often been said that the Catholic church appealed to the peasants in Uganda, and the Anglican church to the elites. By and large, the Anglicans did capture the established elites of Uganda’s diverse societies, and its educational system was geared towards producing the new elites (bureaucrats and teachers) of colonial society.” Ward, 168.

[12] Kivengere, Revolutionary Love, 42, 44.

[13] Archbishop Henry Luke Orombi, What is Anglicanism? August 2007 https://www.firstthings.com/article/2007/08/001-what-is-anglicanism

[14] Bishop Tucker was the bishop of East Equatorial Africa (Uganda, Kenya, Tanzania) from 1890 to 1899 and then Bishop of Uganda from 1899 to 1908. The Church of Uganda became its own province in 1961 with St. Paul’s Namirembe Cathedral as its provincial cathedral, the oldest cathedral in Uganda.

[15] Griphus Gakuru, Anglicanism: A Global Communion (1998), “An Anglican’s View of the Bible in an East African Context,”59.

[16] https://www.westmont.edu/reverence-church-without-shoes