The Rainbow Bodies of the Rainbow People of God: The Last Gospel, Desmond Tutu, and the Powerful Implications of the Incarnation

Readings for the First Sunday after Christmas

This sermon was preached at Christ Episcopal Church Eureka on Sunday December 26, 2021.

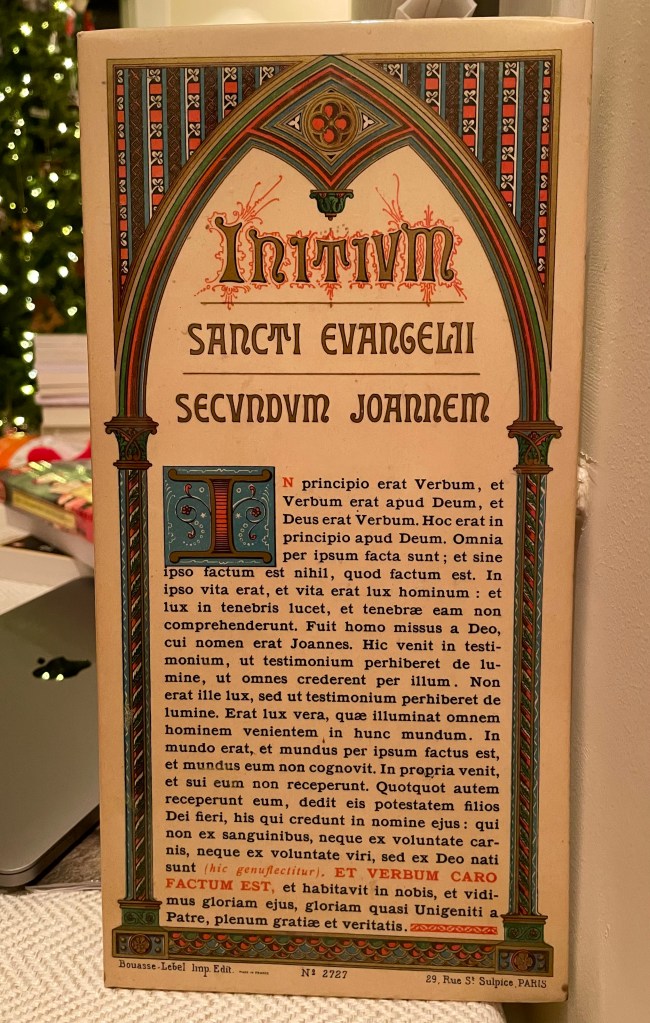

Several years ago, when Ashley and I were visiting friends in Cluny, France, near Taizé, we were shown remnants from an abandoned sanatorium, including items from the hospital’s chapel. Among the items was a plaque with the following words written across the top “Initium Sancti Evangelii Secundum Joannem,” which is Latin for “The Beginning of the Holy Gospel according to John.” Underneath the title are the words of John’s Prologue (which we just heard) with the following words in red: Et Verbum caro factum est, which is Latin for “And the Word became flesh.” And right before these words is a Latin rubric in parenthesis that says, “hic genuflectitur,” which means “kneel down here.” I later learned that this was a remnant from an old liturgical practice that emerged from Salisbury cathedral in medieval England known as the “Last Gospel.” This practice began as a private devotion of the priest who would read, on his own, at the end of Mass, the Prologue of John’s Gospel. Over time, this private devotional practice was absorbed into the official rubrics of the Mass so the priest (not the deacon) would read John’s Prologue after giving the final blessing. Apparently in medieval England, this was the only part of the Latin Mass that was read in the vernacular, in English. And when the priest said, “The Word became flesh,” he and the entire congregation would genuflect. This remained a common practice in Roman Catholic churches until Vatican II, when it was omitted, some say because there were too many superstitious beliefs associated with the reading of these words. Some believed that simply reading these words had the power to drive out demons and evil spirits as well as sickness and disease, which is probably why we found it in an old sanatorium.

I share this nerdy tidbit of church history in order to emphasize the historical and liturgical and spiritual significance of this morning’s Gospel. These days, we hear this reading of John’s Prologue maybe once or twice a year around Christmas time, but for hundreds of years, this was read at the end of every single Mass so that most people had it memorized, especially the most important phrase of all: And the Word became flesh.

I love that this “Last Gospel” practice seemed to have originated in England because the Gospel of John has remained the most favored Gospel among Anglicans. A Roman Catholic New Testament scholar (Benedict Viviano) once told me that Anglicans have a particular weakness for the Gospel of John and I think he’s right. We are indeed susceptible to its allure. Former Archbishop of Canterbury Michael Ramsey thought John’s Gospel had an appeal more timeless than the other Gospels because of its affirmation of the flesh and its universal imagery.[1] And another former Archbishop of Canterbury William Temple said “The Word made flesh” is the most important phrase in all of Christianity.[2] He then explained, “Christianity is the most materialistic of all great religions…. [‘materialistic’ not in the economic sense but ‘materialistic’ in its affirmation of matter]. Based as it is on the Incarnation, [Christianity] regards matter as destined to be the vehicle and instrument of spirit, and spirit as fully actual so far as it controls and directs matter.”[3] In John’s Prologue, it becomes clear that God loves physical matter. He made it, he became it, and he wants us to experience him through it.[4]

Richard Rohr describes the “incarnational piety” of Anglicanism encapsulated in John’s Prologue when he says, “If incarnation is the big thing, then Christmas is bigger than Easter (which it actually is in most Western Christian countries). If God became a human being, then it’s good to be human and incarnation is already redemption. St. Francis and the Franciscans were the first to popularize Christmas. For the first 1,000 years of the church, there was greater celebration and emphasis on Easter. For Francis, if the Incarnation was true, then Easter took care of itself. Resurrection is simply incarnation coming to its logical conclusion: we are returning to our original union with God. If God is already in everything, then everything is unto glory!”[5]

Anglican understandings of the Incarnation resonate deeply with Franciscan spirituality as well as with our Celtic Christian roots, which John Philip Newell seeks to revitalize when he says, “We need to regain confidence in the goodness of creation and thus of the body.”[6] And speaking of our Celtic Christian roots, this morning we catch a glimpse into the world of one of the most ancient Celtic Christian communities in our reading from Paul’s Letter to the Galatians. The Galatians were a Celtic people who lived in Galatia, which is part of modern-day Turkey. Paul refers to them in his letter as “you foolish Galatians!” (3:1) because they kept assuming (wrongfully) that they needed to alter their bodies to in order to be fully accepted by God. Paul kept insisting that all they needed to do was to trust in God’s love as revealed in the Christ who affirmed our flesh as an instrument of his glory. For Paul, it is through faith in God’s love that we become adopted as co-heirs with Christ and enter the same relationship with the Father that Jesus enjoyed. Paul says, “Because you are children, God has sent the Spirit of his Son into our hearts, crying, ‘Abba! Father!’ So, you are no longer a slave but a child, and if a child then also an heir, through God” (Galatians 4:6-7). The same Holy Spirit that dwelled in Christ’s body is now sent into our hearts and bodies, which is why, in his letter to the Corinthians, Paul calls our bodies “Temples of the Holy Spirit” (1 Corinthians 6:19).

This morning’s reading from Galatians includes verses from chapter 3 (23-25) and chapter 4 (4-7), but right in between these verses is a section of Paul’s writings that I consider perhaps his most inspired and brilliant insight into the implications of Christmas, the implications of the incarnation. I feel inspired to read these words with you this morning because these words were central to the spirituality one of the most courageous Anglicans (and Christians) ever, who died just this morning, an Anglican who understood the power of the Incarnation. I had a chance to meet this person and hear him preach a couple times; and my sponsoring priest (Michael Battle) served as his chaplain in the 1990s. Many consider this winner of the 1984 Nobel Peace Prize to be a modern-day saint. He was known as a controversial “Rabble-Rouser for Peace,” but was known throughout the church affectionately as “Arch,” an abbreviation of his full title “Archbishop Desmond Tutu.” He served as the Archbishop of Cape Town from 1986 to 1996 and used his pulpit to speak out boldly against white supremacy and apartheid in South Africa. Like St. Paul, he knew that the Incarnation did not mean that just certain people’s bodies are affirmed and blessed by God, but all human bodies (no matter what color or ethnicity). He referred to us as the “Rainbow People of God” and we see Paul describing this rainbow diversity and inclusivity in the section the lectionary left out. Please turn with me in your Bibles to Galatians 3:26-28 in which Paul, speaking to these ancient Celtic Christians says, “In Christ Jesus you are all children of God through faith. As many of you as were baptized into Christ have clothed yourselves with Christ. There is no longer Jew or Greek, there is no longer slave or free, there is no longer male and female; for all of you are one in Christ Jesus.”

When we see flesh as affirmed by God as a vehicle for his glory, we begin to see how every human body has been anointed with God’s love and stamped with God’s blessing and approval. Towards the end of his letter to the Celtic Christians of Galatia, Paul says, “I carry the stamp of Christ on my body” (6:17). If the incarnation is true, if the Word became flesh, then we are all fully loved and accepted by God in our bodies now; and when we eventually shuffle off these mortal bodies, these temporary temples of the Spirit, we will rise again in Risen Bodies like the Risen Jesus Christ our Lord, Risen Bodies that might be akin to what the Tibetan Buddhists call “Rainbow Bodies.” The Rainbow Bodies of the Rainbow People of God. That’s why the most ancient creed we have (the Apostle’s Creed) does not just say we believe in the resurrection of the dead, but we believe in the “resurrection of the body” because God loves us as his very own children and because God loves our bodies as vehicles for his glory. As Desmond Tutu said, “We are made for goodness. We are made for love. We are made for friendliness. We are made for togetherness. We are made for all of the beautiful things that you and I know. We are made to tell the world that there are no outsiders. All are welcome: black, white, red, yellow, rich, poor, educated, not educated, male, female, gay, straight, all, all, all. We all belong to this family, this human family, God’s family.” This is why John’s Prologue is so important and why our ancestors would kneel frequently in gratitude and awe every time they heard the mystery of the Incarnation revealed in that most consequential phrase: Et Verbum Caro Factum Est; And the Word became flesh. Amen.

[1] Michael Ramsey, The Christian Priest Today (Eugene OR: Wipf and Stock, 1982), 29.

[2] “[Christianity’s] own most central saying is: ‘The Word was made flesh,’ where the last term was, no doubt, chosen because if its specially materialistic associations” from Nature, Man and God: Gifford Lectures, Lecture XIX: ‘The Sacramental Universe” (London: Macmillan), p. 478 as cited in Christ In All Things: William Temple and His Writings, ed. Stephen Spencer (Norwich: Canterbury Press, 2015), 130.

[3] William Temple, Readings in St. John’s Gospel (London: Macmillan, 1945), xx-xxi. Also in Lecture XIX of the Gifford Lectures, he says, “[Christianity] is the most avowedly materialist of all the great religions” as cited in Christ In All Things: William Temple and His Writings, ed. Stephen Spencer (Norwich: Canterbury Press, 2015), 130. This affirmation of the Incarnation and an appreciation for the Gospel of John have remained dominant characteristics within Anglicanism.

[4] “In The Spirit of Anglicanism, William J. Wolf writes of ‘an incarnational piety’ that has always dominated Anglicanism. Anglicanism has, in a way, appropriated the Feast of the Nativity as a celebration of its own particular ethos. [Lancelot] Andrewes, for example, preached more sermons for Christmas day than for any other occasion. Of Donne’s 160 surviving sermons, the Christmas sermon for 1621, on John 1:18, is one of the most eloquent.” P.G. Stanwood, John Donne: Selections from Divine Poems, Sermons, Devotions, and Prayers (Mahwah NJ: Paulist Press, 1990), 3.

[5] https://cac.org/incarnation-already-redemption-2015-06-05/

[6] Newell, Listening to the Heartbeat of God, 102