Readings for the Third Sunday after Pentecost (Proper 7 – Year A) – Father’s Day

Genesis 21:8-21

Psalm 86:1-10, 16-17

Romans 6:1b-11

Matthew 10:24-39

This sermon was preached at Christ Episcopal Church Eureka on Sunday June 21, 2020. Worship Program here.

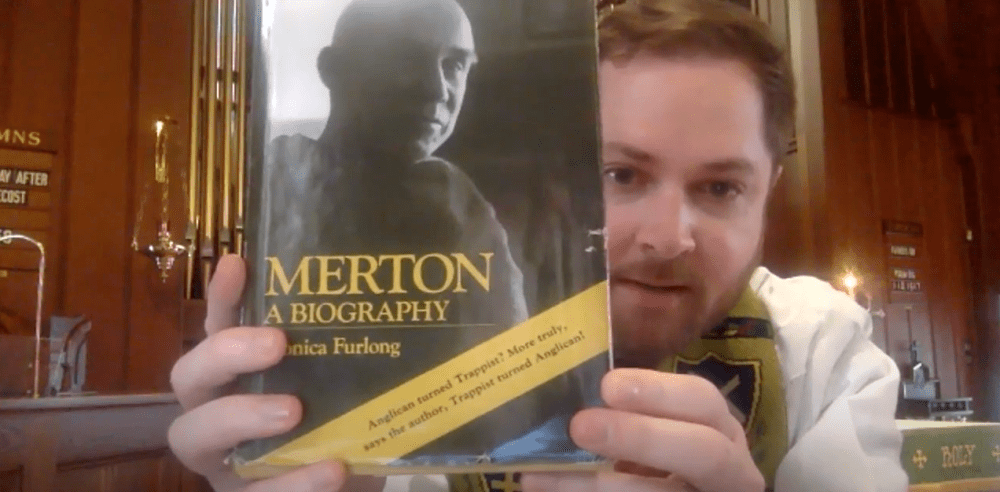

Happy Father’s Day! It’s good to be back after a prayer retreat on this Father’s Day; and on this Father’s Day, I’d like to talk about an author whom my father introduced to me when I was 12 years old, an author whose words guided my prayers and contemplation during my prayer retreat, and an author whose life is described in a book that I borrowed from the Father Doug Memorial Library here at Christ Church Eureka. The author is a Trappist monk from Kentucky named Thomas Merton who died in Bangkok Thailand in the late 1960s after writing some of the most influential books on Christian Spirituality. The book I borrowed from the Fr. Doug Library is called Merton: A Biography, written by an Anglican author named Monica Furlong. The blurb on the cover of this copy says “Anglican Turned Trappist? More truly, says the author, Trappist turned Anglican!” The author never really makes that argument in the book (that he turned Anglican) but I imagine the blurb helped boost sales among Anglicans and Episcopalians. And this biography was indeed popular among Episcopalians and I like to think that this was Father Doug’s personal copy, replete with some of his own coffee stains and candy wrappers, hidden between the pages.

Thomas Merton was a cosmopolitan kid, born in France to a New Zealand artist and an American Quaker, baptized in the Church of England, raised on Long Island, and then Scotland, Bermuda, Cambridge, and Manhattan and more, before settling in Kentucky at the Abbey of Gethsemani. While on Long Island, his father (Owen Merton) served as a church organist at Zion Episcopal Church in Douglaston NY, a church that Merton described as very much like our own, with an eagle lectern, an American flag, and stunning stained glass windows behind the altar. Regarding the Episcopal Church, young Merton said: “one came out of the church with a kind of comfortable and satisfied feeling that something had been done that needed to be done.”[1]

It was at a young age that Thomas Merton also suffered the tragic loss of his mother and then his father (both to cancer). These painful tragedies pushed Merton first into a deep depression, but then eventually deeper into prayer. He wrote about his first experience of deep prayer and contemplation. He said, “I was in my room. It was night. The light was on. Suddenly it seemed to me that Father, who had now been dead more than a year, was there with me. The sense of his presence was as vivid and as real and as startling as if he had touched my arm or spoken to me. […] And […] for the first time in my whole life I really began to pray—praying not only with my lips and with my intellect and my imagination, but praying out of the very roots of my life and my being, and praying to the God I had never known, to reach down towards me out of His darkness and to help me to get free from the thousand terrible things that held my will in their slavery.

“There were a lot of tears connected with this, and they did me good, and all the while, although I had lost that first vivid, agonizing sense of the presence of my father in the room, I had him in my mind, and I was talking to him as well as to God.”[2] This profound experience of prayer planted a seed within Merton that he eventually chose to water and grow and cultivate with tremendous discipline and care as a Trappist monk. For those who don’t know, the Trappists are Benedictine monks who are part of the Order of Cistercians of the Strict Observance. They are essentially not permitted to speak. They live in silence and only open their mouths when they gather for prayer seven times a day, starting each day at 2 AM. And each week, they pray the entire Psalter, all 150 Psalms.

And it was the Psalms that helped Merton continue to pray out of the very roots of his life and his being, asking God to continually reach down toward him and help him and the entire world be set free from the thousand terrible things that held humanity in slavery. For Merton, that included racial injustice, the nuclear arms race, violence, and greed. It was prayer that compelled Merton to write about these issues, even when others thought he should not rock the boat of the Catholic Church and not disturb the “peace” of the status quo;[3] and it was these issues that compelled him to continue praying more deeply, and to pray in the words of the Psalms.

In a book titled “Bread in the Wilderness,” Merton wrote about the Psalms. He himself was a prolific poet and he called the Psalms “the simplest and greatest of all religious poems”[4] that “enter into every department of life”[5] and cover the entire range of human emotions. He also said that “the reality which nourishes us in the Psalms is the same reality which nourishes us in the Eucharist, though in a far different form. In either case, we are fed by the Word of God. In the Blessed Sacrament, ‘His flesh is food indeed.’ In the Scriptures, the Word is incarnate not in flesh but in human words.”[6] This is an important teaching for us right now as our Presiding Bishop Michael Curry has encouraged us to make greater use of the Daily Office, to pray Morning Prayer (as we’ve been doing) and “to recover aspects of our tradition that point to the sacramentality of the scriptures [and] the efficacy of prayer itself.”[7]

As we fast from the Word of God made flesh in the Holy Eucharist, let us feast on the Word of God that speaks to us through our Scriptures, specifically through the Psalms, which are “the historical and theological center of the Daily Office.”[8] This is an important distinction between Morning Prayer and the Liturgy of the Word in Holy Eucharist. During Holy Eucharist, we emphasize the Gospel reading with a gradual hymn and procession and a special call and response called the Gospel Acclamation. But in Morning Prayer, we don’t do any of that because the heart of the prayer service is the Psalm, which we chant together at the beginning of the liturgy. Merton explained that the Psalms have an advantage over the New Testament readings (including the Gospel), because “we pray [the Psalms]. We chant them together. They form part of an action into which the whole Church enters, and in that action, that prayer, the Spirit of Love Who wrote the Psalms and Who communicates Himself to us in them, works on us all and raises us up to God.”[9]

I invite you to look at the Psalm that we just chanted this morning, remembering this is the heart and the core of the Morning Prayer service. The psalmist says, “Bow down your ear, O LORD, and answer me, for I am poor and in misery” (86:1). These honest and naked words of sorrow and poverty are brought to God in prayer. Let’s admit that we are collectively in a period of depression right now as a country, as we all face the consequences of COVID-19 and systemic racism. I think we are all grieving to some degree. I’m so glad to be back in this space, but it’s also heartbreaking because you’re not here with me, filling this place with your joy and warmth and love. This is a time for us to plunge deeply into the river of the Psalms, which give voice to our pain and sadness while also promising us that we are being heard by God when we pray, even when it might feel like God is distant. God listens to our prayers and our cries. The Psalms say that God collects our tears in his bottle (56:8). God hears us just as he heard the tear-soaked prayers of Hagar and Ishmael (Gen 21:17). So let us bring all of our concerns, fears, anxieties and sorrows to the Psalms and then allow ourselves to be swept away, as Merton says, “on the strong tide of hope, into the very depths of God.”[10] In this way we can join the psalmist who at the conclusion of this morning’s Psalm says with confidence: “You, O LORD, have helped me and comforted me” (86:17). We can rest in the promise that God knows the number of hairs on our head; that His eye is on the sparrow and we know he watches us.

As I was reading the Merton biography from the Fr. Doug Library, I remembered sitting beside Fr. Doug on the day he died and praying Psalm 91. And during my father’s final days, we would often read the Psalms by his bedside. My father was always comforted by the Psalms. They would encourage him in his difficult battle with leukemia because the psalmists were often fighting battles for their lives as well. Hearing the Psalms gave him perspective: things were hard for him, but things were much worse for the psalmists who were often in extremely desperate situations.

My dad also knew that some of the best psalms of the Bible are not even in the book of Psalms. One beautiful psalm that celebrates God’s saving help is from the 12th chapter of Isaiah and it’s called “The First Song of Isaiah.” We just sang it a few moments ago and I want us to sing it again. It’s on page 5 of your worship bulletin and as you turn there, notice the name of the music, the tune (in the upper right hand corner). Dr. Ray Urwin, the minister of music at an Episcopal Church in southern California,[11] wrote this tune and named it Thomas Merton in honor of the Trappist monk. As we sing together the words of this ancient psalm, may we be encouraged by the faith of our fathers as we face an unknown future, and may we be swept away by the strong tide of hope into the very depths of God. Amen.

[1] Thomas Merton, The Seven Storey Mountain: An Autobiography of Faith (Harcourt, 1948), 15.

[2] Merton, SSM, 123.

[3] This is the peace that Jesus refers to in this morning’s Gospel (Matthew 10:24-39). Although Jesus is indeed the Prince of true Peace, he did not come to reinforce the peace of the status quo, which was the Pax Romana, the “peace” that pacified others militarily, economically and politically in order to fatten the purses of the wealthy and oppress the poor. Jesus brought a sword that punctured the heart of the Pax Romana, which is why Rome crucified him. See Warren Carter, Matthew and Empire: Initial Explorations (Trinity Press: Harrisburg PA, 2001).

[4] Thomas Merton, Bread in the Wilderness (Fortress Press: Philadelphia, 1953), 71.

[5] Merton, BW, 7.

[6] Merton, BW, 9.

[7] https://www.episcopalnewsservice.org/pressreleases/a-word-to-the-church-on-our-theology-of-worship-from-the-presiding-bishop/

[8] Derek Olsen, Inwardly Digest: The Prayer Book as Guide to a Spiritual Life (Forward Movement: Cincinnati OH, 2016), 184.

[9] Merton, BW, 133.

[10] Merton, BW, 93.

[11] St. Michael and All Angels Corona del Mar, https://www.stmikescdm.org/clergy-and-staff/