Readings for the Seventeenth Sunday after Pentecost (Proper 22 Year C)

Lamentations 1:1-6

Lamentations 3:19-26

2 Timothy 1:1-14

Luke 17:5-10

This sermon was preached by Fr. Daniel London at Christ Episcopal Church in Eureka CA on October 6, 2019.

1870 was the year that this parish was founded. It was also the year that the great French novelist Alexandre Dumas died. Before he died, Dumas wrote many classic French novels such as The Three Musketeers, The Man with the Iron Mask, and The Count of Monte Cristo. As I was prayerfully reading this morning’s Gospel, I remembered a passage from The Count of Monte Cristo in which the protagonist Edmond Dantés has a conversation with a Catholic priest and mentor named Abbé Faria in the Chateau d’If, a prison island in which they have both been wrongfully sentenced. Moments before dying, Abbé Faria said to Edmond Dantés, “Here is your final lesson: do not commit the crime for which you now serve the sentence [in other words, do not seek revenge. For] God said, ‘Vengeance is mine.’”

Edmond Dantés responded by saying, “I don’t believe in God.”

“It doesn’t matter,” Abbé Faria replied, “He believes in you.”

I sense a similar kind of wisdom being offered in our Gospel reading this morning, in which the apostles ask Jesus, “Increase our faith!” as if faith were something to be quantified and used to make God love us more, or worse, to try to control and manipulate God. Jesus’s response to the disciples’ request invites them to do the same thing that Abbe Faria invites Edmond Dantes to do: to turn their focus away from themselves and away from how much faith they can acquire or accumulate and rather turn their focus towards their God, who loves them no matter what, who longs for their healing and wholeness, and who believes in them, regardless of how much or little they might believe in him. As Bishop Tom Wright says, “You don’t need great faith. You need faith in a great God.”

This is what Jesus is teaching in his own unique and challenging and even disturbing way. The story he tells about the slaves who see themselves as worthless and undeserving of their master’s gratitude may sound quite off-putting to us today. But I believe this is Jesus’s way of saying, “It’s not about you or how much you believe or how much theological education you might have or how many Bible verses you’ve memorized. It’s about God’s unconditional love for you and your openness to receiving and sharing that love.” All of our church doctrines and dogmas and creeds and Bible verses are good and necessary, but they are ultimately worthless in and of themselves. They are only helpful insofar as they do what “they have been ordered to do”: to lead us into God’s love. All of these things—our doctrines, our scriptures, our faith, our liturgy—are all slaves to God’s love. Even this gorgeous church building, which was recently “plucked like a brand from the burning,” and for which I give thanks to God every day, is still a slave to God’s love.

The book of Lamentations offers this same message as it describes in poetic detail the enormous suffering that the people of Judah endured in losing all the great symbols of their faith, especially their glorious temple. They lost their king, their capital, their safety, their health, their freedom and so much more. With all of this gone, they were left with the only thing that mattered: God’s love for them. They came to the realization that everything they have ever enjoyed in this world (their temple, their health, their money) was all intended to bring them to receive and share God’s love. And even with all of that gone, God’s love still remains.

We together just read the conclusion to the book of Lamentations. Ancient Near Easter texts have what is called a chiastic structure, which means that the conclusion of the text does not come at the end but rather right in the middle. And that is what we just read in Lamentations chapter 3: the central conclusion in which the author says, “The thought of my affliction and my homelessness is wormwood and gall! My soul continually thinks of it and is bowed down within me.” (3:19-20). In other words, “I’ve lost everything that ever brought me joy. Everything that made me experience God’s love has been ripped away from me.”

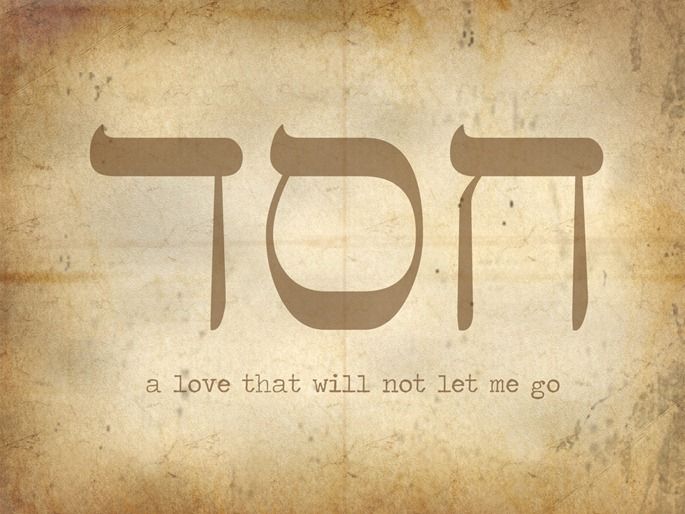

“But,” he continues, “this I call to mind and therefore I have hope: the steadfast love of the LORD never ceases, his mercies never come to an end; they are new every morning; great is your faithfulness” (3:21-23). I want to teach you a Hebrew word that the Bible translates as “steadfast love.” The word is chesed. If you have trouble making that guttural ch sound, you can just say, hesed. There is no great translation for this word, but “steadfast love” is pretty good. Chesed is God’s unconditional commitment and eternal affection for you. It is associated with the love expressed through a covenant (a holy agreement and commitment) and is sometimes called “covenant love.” But the chesed of God remains available to us even when we mess up, even when we break our part of the covenant. The chesed of God never ceases. Our love for God and our belief in God are good and need to be cultivated, but ultimately our job is to rest in God’s love for us, God’s belief in us, God’s chesed, because even when we doubt God, his steadfast love for us never ceases. Even when we don’t believe, God believes in us.

We are now celebrating our 150th anniversary and our theme is “Steadfast and Growing since 1870.” We are steadfast indeed and we are growing in ways we cannot yet even imagine. We have been resilient in the face of some serious challenges, including the recent fire at our front door. We should celebrate our history and our resilience and our growth, but more than all of that, we are called to glorify God by simply resting in his steadfast love, resting in God’s chesed. It is God’s love that can move mountains and uproot trees and we can participate in that divine power not so much by prophesying or preaching or speaking in tongues or increasing our faith, but by simply resting in God’s love, in basking in our belovedness. As the Apostle Paul said, “If I speak in tongues of men or of angels, but do not have love, I am a resounding gong or a clanging cymbal. If I have the gift of prophecy and can fathom all mysteries and all knowledge, and if I have a faith that can move mountains, but do not have love, I am nothing. If I give all I possess to the poor and give over my body to hardship that I may boast, but do not have love, I gain nothing.” (1 Corinthians 13:1-3). All that matters is receiving and sharing God’s steadfast love.

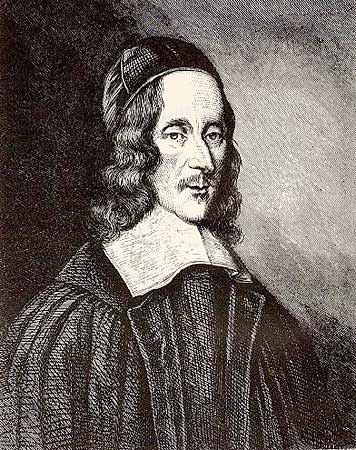

I invite you to rest in God’s chesed as you hear these words of a poem by 17th century Anglican priest George Herbert. I invite you to let these words wash over you so that may you may know in your bones and sinews that no matter how much or how little you believe in God, God believes in you. God’s steadfast love for you never ceases. The poem is appropriately titled “Love.”

Love bade me welcome; yet my soul drew back,

Guilty of dust and sin.

But quick-eyed Love, observing me grow slack

From my first entrance in,

Drew nearer to me, sweetly questioning

If I lacked anything.

“A guest,” I answered, “worthy to be here”:

Love said, “You shall be he.”

“I, the unkind, ungrateful? Ah, my dear,

I cannot look on thee.”

Love took my hand, and smiling did reply,

“Who made the eyes but I?”

“Truth, Lord; but I have marred them; let my shame

Go where it doth deserve.”

“And know you not,” says Love, “who bore the blame?”

“My dear, then I will serve.”

“You must sit down,” says Love, “and taste my meat.”

So I did sit and eat.

One thought on “Rest in God’s Chesed”