Readings for the Seventh Sunday after Pentecost (Proper 12 Year C)

Hosea 1:2-10

Psalm 85

Colossians 2:6-15, (16-19)

Luke 11:1-13

This sermon was preached by Fr. Daniel London at Christ Episcopal Church in Eureka CA on July 28, 2019.

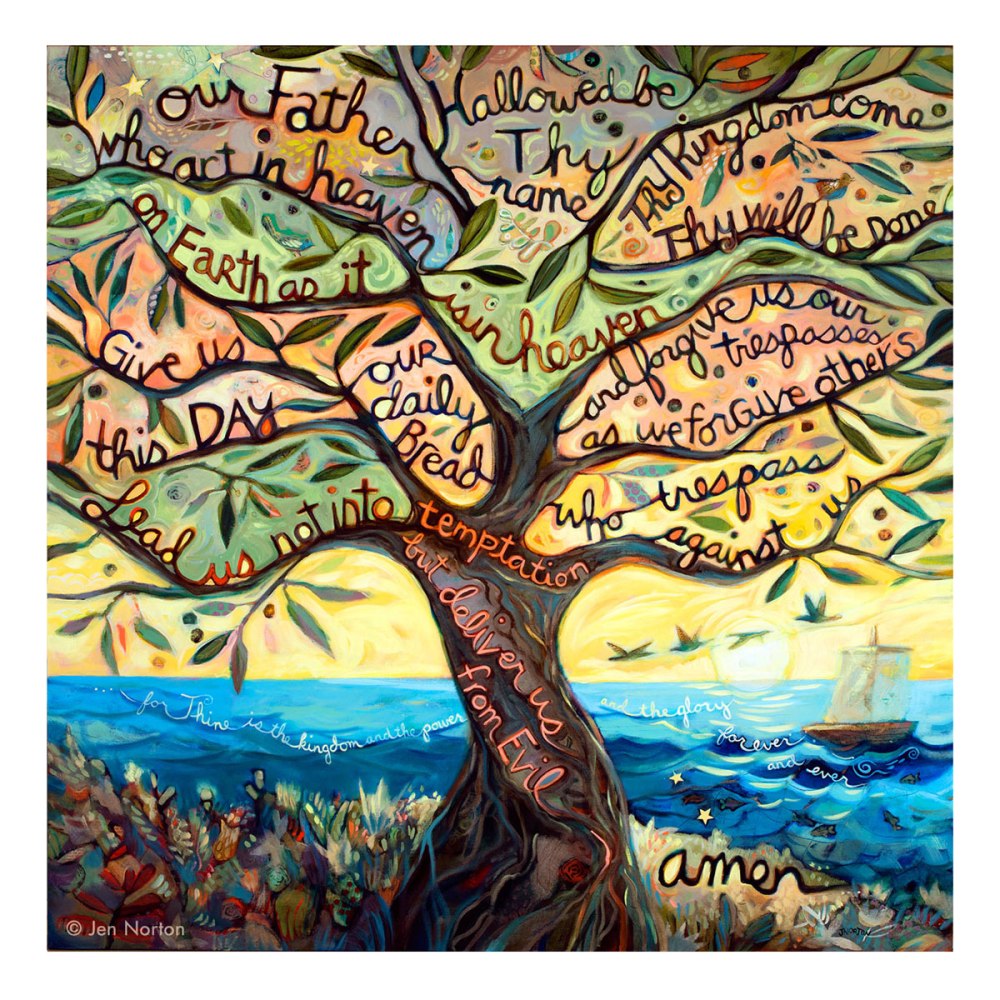

One of my earliest memories is gathering with my brother and my parents in our living room on Seena Avenue in Los Altos California to learn about and then memorize the Lord’s Prayer. I remember us meeting seven nights in a row so that each night my parents could teach my brother and me a new phrase in the prayer. On the first night, we learned “Our Father who art in heaven.” On the second night: “Hallowed be thy name.” On the third night: “Thy kingdom come, thy will be done on earth as it is in heaven.” And so on. I’m sure many of you have similar childhood memories of learning and memorizing this beloved prayer. And if not, I’d be curious to hear how you were first introduced to this prayer that Christ taught his disciples.

I have heard some funny stories about children mis-hearing and thus mis-memorizing words of this prayer saying things like, “Our Father who art in Heaven, how didja know my name?” or “Our Father who art in Heaven, Howard be your Name.” Or “Give us this day our jelly bread.” Or “Give us this steak and daily bread, and forgive us our mattresses.”

For many of us, this ancient prayer connects us deeply with our kith and kin, our parents and grandparents, our relatives and distant ancestors. In fact, the words of the Lord’s Prayer are likely the only words that have remained unchanged in our liturgy during the 150 years of Christ Church Eureka. When we pray the Lord’s Prayer we are praying the same words that our founder Thomas Walsh and our first rector John Gierlow and our first Christ Church Eureka members prayed so long ago. For decades, this prayer has echoed within this nave and has seeped into the furniture. Our pews and stained-glass windows have been absorbing these words for 150 years now. This is surely a place where, in the words of T. S. Eliot, “Prayer has been valid.” Although our prayer book gives us the option of praying a more contemporary version of the Lord’s Prayer after the Eucharistic Prayer, I don’t feel compelled to use this because so many of us find comfort in the beautiful and poetic words of the traditional prayer and that’s a good thing. However, we also know how easy it is for us to daydream and to lose focus whenever we say the same words over and over again by rote, week after week. Are we really paying attention to the meaning and the power of the words that we so boldly pray?

Our Gospel reading today includes St. Luke’s version of the Lord’s Prayer, which is a fairly abbreviated version of the one with which we are most familiar, from chapter 6 of the Gospel of Matthew. This different version invites us to hear the Lord’s Prayer anew, to hear it again for the first time, to pay attention to the meaning and power of the words that we so often pray. Throughout this week and throughout this summer, I encourage us all to spend some quality time intentionally meditating upon the words and phrases of this prayer (both Luke’s version and Matthew’s version). I encourage you do this with your family, with your friends or within the silence of your own hearts. Bishop Tom Wright issues this invitation when he says, “Take each clause at a time, and, while holding each in turn in the back of your mind, call into the front of your mind the particular things you want to pray for […] under that heading. Under the clause, ‘Thy Kingdom Come,’ for example, [you may want to pray for] the peace of the world, with some particular instances [in mind]. The important thing is to let the medicine and music of the prayer encircle the people for whom you are praying, the situations about which you are concerned, so that you see them transformed, bathed in the healing light of the Lord’s love as expressed in the prayer.” (Wright, The Lord & His Prayer. William B. Eerdmans: Grand Rapids MI 1996, 7-8). By doing this, we can explore the many riches of this prayer, which is our spiritual inheritance as followers of Christ. And, again to quote T. S. Eliot, “the end of all our exploring will be to arrive where we started and know [this prayer again] for the first time.”

I have found that one of the most effective ways to hear the Lord’s Prayer again for the first time is to hear the eloquent way that our Anglican brothers and sisters in New Zealand have translated and interpreted the words that Jesus gave us. It is important to remember that Jesus of Nazareth never said the actual words, “Our Father who art in heaven,” because Jesus did not speak English. He probably said something like “Avinu She-ba-shamayim,” a Hebrew phrase which was then written in the Greek as “Pater humon ha en tois ouranois” which was then translated to English as “Our Father who art in heaven.” All translations are interpretations so it is helpful for us to hear how other cultures interpret the words of Jesus because such interpretations can capture crucial meanings that can easily get lost in our own translations. I believe this is the case when it comes to the Lord’s Prayer from the New Zealand Anglican prayer book, which was published in 1989, and goes like this:

Eternal Spirit,

Earth-maker, Pain-bearer, Life-giver,

Source of all that is and that shall be,

Father and Mother of us all,

Loving God, in whom is heaven:

The hallowing of your name echo through the universe!

The way of your justice be followed by the peoples of the world!

Your heavenly will be done by all created beings!

Your commonwealth of peace and freedom

Sustain our hope and come on earth.

With the bread we need for today, feed us.

In the hurts we absorb from one another, forgive us.

In times of temptation and testing, strengthen us.

From trials too great to endure, spare us.

From the grip of all that is evil, free us.

For you reign in the glory of the power that is love,

Now and forever. Amen.[i]

This last week I participated in a class on the late poet Mary Oliver, who understood poetry as a form of prayer. She attended St. Mary of the Harbor Episcopal church in Provincetown MA and referred to the Episcopal Church in one of her poems as “that strange, difficult, and beautiful church.”[ii] What emerged for me during this class as well as during the meditation retreat I led in Trinidad was the posture of receptivity in prayer. Mary Oliver’s poems can so easily be read as prayers because of how effectively she communicates her receptivity to God in nature: in dirt, in trees, in birds and ponds. Instead of hurling petitions and complaints and disappointments toward God (as I sometimes do), Mary Oliver opens herself up to receiving the thousands of good gifts that God lavishes upon her (and upon each of us) every day. And she then shares what she receives because whatever we receive from God in prayer, we are expected to share, just like the persistent friend in today’s parable, who bangs on his friend’s door for bread in the middle of the night not because he’s hungry but because he wants to share food with his guest.

So as we pray the Lord’s Prayer, I invite us to hold a posture of receptivity, knowing that whatever we receive in prayer we are expected to share. May we receive God as our loving parent. May we receive the kingdom come, the kingdom which is the voice of divine love reigning supreme in our hearts and lives. May we receive the ten thousand good gifts that God bestows upon us each day. May we receive forgiveness, salvation and everlasting life. And whenever our selfishness drives us to reach out foolishly for scorpions and snakes, may we instead receive from God the refreshing nourishment he offers us each moment in the grace of his Holy Spirit. May we receive the grace of the Holy Spirit through the words of one of Mary Oliver’s poems titled “Praying”[iii]:

It doesn’t have to be

the blue iris, it could be

weeds in a vacant lot, or a few

small stones; just

pay attention, then patch

a few words together and don’t try

to make them elaborate, this isn’t

a contest but the doorway

into thanks, and a silence in which

another voice may speak.

[i] A New Zealand Prayer Book: He Karakia Mihinare o Aotearoa (HarperCollins: New York, 1989), 180.

[ii] Mary Oliver, “After Her Death” from Thirst (Beacon Press: Boston MA, 2006), 16.

[iii] Mary Oliver, “Praying” from Thirst (Beacon Press: Boston MA, 2006), 37.

[i] Mary Oliver, “After Her Death” from Thirst