INTRODUCTION:

“An Arbiter Between Us”

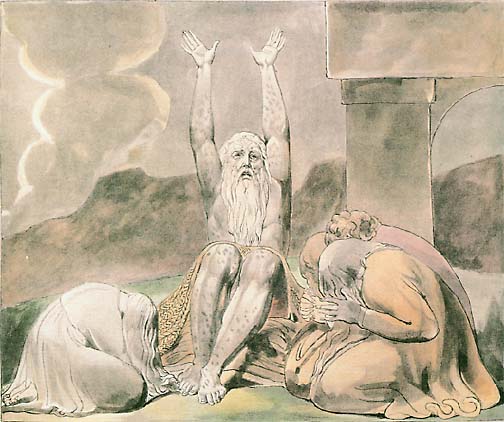

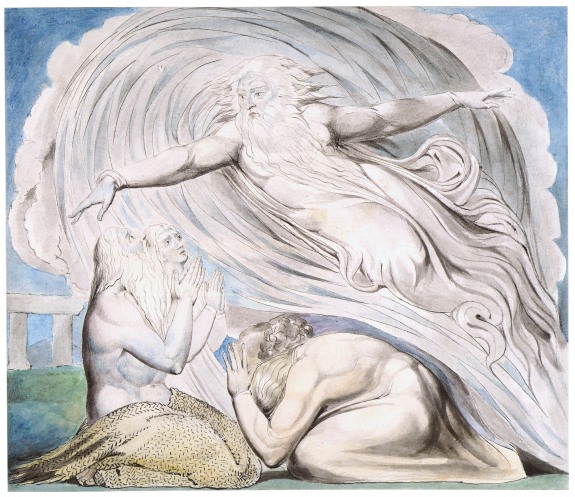

Overwhelmed with grief and coated with boils, the righteous man Job sits in ashes and laments, “There is no arbiter between us.” His comforters, who appear to offer more consolation in their silence than in their speech, understand that the “us” in Job’s complaint comprises Job and his God. Because the meaning of the Hebrew in the book of Job often proves ambiguous and recondite, translators also suggest Job’s grievance to hint at least some hopeful possibility: “If only there were an arbiter between us.”[1] Feeling terrorized by God’s excessive and unjustifiable castigation, Job expresses his need for a mediator between himself and an (ostensibly) unlawful God. Jewish philosopher Martin Buber reads Job’s complaint as his prayerful struggle to “see God as His witness against God Himself.”[2] The only mediator sufficiently qualified to adjudicate between humanity and God is God.

Although the book of Job is within the Jewish canon of Hebrew Scriptures, Job himself is not Jewish and is therefore unfamiliar with the Torah, thus lacking the Jewish assurance that God upholds justice as well as the tool to remind God of His ethical standards.[3] Though he eventually finds assurance in divine justice, Job still struggles to see this divine justice as connected with the God who has abused him. Again, Buber weighs in,

Job’s faith in justice is not broken down. But he is no longer able to have a single faith in God and in justice. His faith in justice is no longer covered by God’s righteousness. He believes now in justice in spite of believing in God, and he believes in God in spite of believing in justice. But he cannot forego his claim that they will again be united somewhere, sometime, although he has no idea in his mind how this will be achieved.[4]

As the book progresses, Job’s pessimism about the possibility of a divine mediator turns a corner into hopeful assurance as “no arbiter between us” (9:33) becomes “My witness is in heaven, and he that vouches for me is on high” (16:19) and “I know that my Redeemer lives” (19:25). Job does not attempt to explain how God will judge God or offer any precise details regarding the divine mediator, because, according to Buber, he does not know. “How will it take place? Job does not know this, nor does he understand it; he only believes in it.”[5]

The job description of Job’s divine mediator is fairly clear: first, applicants must be able to judge fairly between humanity and God; and second, applicants must be divine, which, within the strict monotheism of Judaism, narrows the pool of applicants down quite a bit. However, within this finite pool (open only to the Infinite), two candidates successfully emerged to fulfill the role. For Christians, it was Jesus of Nazareth. For Jews, it was the Torah. In this paper, I will argue that by seeing the Torah as the divine mediator, Jews empowered themselves with an effective tool to judge God in the tradition of protest theology and protest prayer. On the other hand, by seeing Jesus as the divine mediator, Christians emptied themselves of any need to arbitrate between humanity and divinity, a duty that Christ has already fulfilled.

PROTEST PRAYER THAT JEWS AND CHRISTIANS SHARE

Thunderstorms, floods, volcanoes, earthquakes and other deadly disasters forced ancient peoples to confront their fragile mortality. Just as the Babylonians, the Persians, the Greeks and other surrounding peoples associated these natural threats with the expressions of irascible gods at war, so did the Hebrews learn to associate the natural threats with expressions of their own irascible God, perhaps at war with Himself. Yochanan Muffs discusses how the anthropomorphization of the gods takes on new color in a monotheistic tradition: “The new idea in the Bible is not the idea of one God, but rather the revelation of a new concept of personality. The divine personality is, to a great degree, the mirror image of man’s understanding of himself.”[6] Perhaps in order to give themselves some semblance of control and safety in the midst of such severe and fatal threats, the Hebrew people began to believe that they might have some influence on this God and His emotions and, therefore, on the consequent catastrophes.

The majority of Hebrew prayers include praise, thanksgiving and adulation, expressing gratitude for God’s good gifts as well as for His protection and liberation. One might conjecture that some of these Hebrew prayers—or any prayers for that matter—expressed praise or flattery to God in order to encourage or coerce God to continue showering down good gifts and to keep danger at bay. A more straightforward and perhaps honest approach to influencing God for the benefit of humanity emerges in the protest prayer tradition. Although William Morrow highlights other names that have been used for this tradition (“Lament…prayers of complaint, arguing with God”), I will use the name “protest prayer” to describe the tradition that protests against the suffering in the world (past, present and future) to the One who is judged most responsible for that suffering, in the hope that He can do something to alleviate it.[7] In other words, God is in control of all things and is, in fact, doing an awful job or at least needs a little help from His human friends in order to do his job better. In protest prayer, God can be judged, blamed and held accountable for the suffering in the world and can also be the target of human frustration and anger.

Both Judaism and Christianity share the protest prayer tradition contained within the Hebrew Scriptures. Considering the hundreds of years over which the Hebrew Scriptures were written and redacted, it would be a mistake to portray the biblical protest prayer tradition as a monolithic category. The tradition, of course, developed over the centuries, while waning in and out of popularity. Authors like William Morrow have attempted to trace the historical course of the tradition based on the biblical evidence. Although I will not pursue such an ambitious endeavor here, I will highlight two types of protest prayer within the Hebrew Scriptures that suggest a significant movement and expansion of the tradition over time: 1) the prophetic protest prayer in which the prophet prays boldly on behalf of others and 2) the personal protest prayer in which one’s personal liberation is the subject of the prayer.

Prophetic Intercession

According to Jon D. Levenson, “One of the most remarkable features of the Hebrew Bible” is not just the opportunity that people can argue with God, but “the possibility that people can argue with God and win.”[8] The audacity to seize such opportunities to argue with God is a quality displayed by the biblical prophets, who argue with God on behalf of God’s people. When God grows incensed with his creatures and feels the urge to stomp them out, a prophetic voice often disrupts God from carrying out his destruction. A prophet, according to Yochanan Muffs, is not just someone who declares God’s harsh decrees, but “an independent advocate…who attempts to rescind the evil decree by means of the only instruments at his disposal, prayer and intercession.”[9] Abraham steps into this prophetic role when he bargains with God on behalf of Sodom and Gomorrah, asking, “Shall the Judge of the world not do justice?” (Gen. 18:25). “This,” Richard Elliott Friedman writes, “is the first time in the Bible that a human questions a divine decision.”[10] Although Sodom and Gomorrah do eventually suffer God’s wrath, Abraham succeeds in talking God down to sparing the city if only fifty, then forty-five, then forty, thirty, twenty, and finally ten righteous people can be found. The God of Bereshith is not teasing Abraham like a cruel older brother who lets his younger brother earn some hopeful points only to squash him. God does not know how many righteous people might be found in Sodom as God Himself admits: “I will go down to see whether they have acted altogether according to the outcry that has reached Me; if not, I will take note” (Gen 18:21).[11] God is willing to withhold his destruction if ten righteous people are found. By taking the role of prophet, Abraham puts God at risk of changing His plans. According to Levenson, “Abraham doubts, questions, argues and even convinces God to back down from an extreme position.”[12]

Although bold and bordering on brash, Abraham sprinkles his intercessory argument with humble declarations: “I who am but dust and ashes” (18:27) and “Let not my Lord be angry if I speak but this last time” (18:32).[13] “[These] apologies,” Levenson explains, “capture the two-sidedness of the situation perfectly: they express both the necessity and the absurdity of a person’s telling God what to do. They acknowledge both the justice of human protest against the dubious counsels of God and the inherent limitation upon the right of human beings to lodge such a protest.”[14]

Abraham asks and argues on behalf of Sodom, and God responds by revealing his willingness to be moved, persuaded, and perhaps reminded of his own eagerness to forgive and reluctance to punish. The prophet intercedes on behalf of others by reminding God of his mercy. “Prophecy,” Muffs explains, “does not tolerate prophets who lack heart, who are emotionally anesthetized. Quite the contrary, one could even argue that, historically speaking, the role of intercessor is older than the messenger aspect of prophecy. After all, Abraham is not a prophet messenger, yet he is considered a prophet nonetheless.”[15] Although Abraham generally does not enjoy the status of prophet in Judaism (as he does is in Islam), the Jewish Study Bible explains, “In this section [Gen. 18:16-33], God treats Abraham as a prophet, disclosing His plans to him, and Abraham, like one of the prophets of Israel, eloquently demands justice for God and pleads for mercy.”[16]

In his essay “Who Will Stand in the Breach? A Study of Prophetic Intercession,” Muffs surveys the intercessory arguments of prophets as they protest against God’s devastating anger in the hope of diminishing painful punishment. Moses argues on behalf of Miriam (Num 12:13) and Aaron (Deut 9:20) and the Israelite people, all of whom God, at one time or another, wants to obliterate. Moses appeals to God’s reputation and reminds God of His former promises and, like a friend holding someone back at a budding bar fight, the protest prayers of the prophet restrain God’s fists from clobbering God’s people. [17] In his creative and iconoclastic book Joseph’s Bones: Understanding the Struggle Between God and Mankind in the Bible, Jerome M. Segal offers a colorful interpretation of Moses’ role as intercessor:

Moses….has been chosen by God precisely in order to protect the Israelites from God himself. Moses, named by Pharaoh’s daughter to signify ‘I drew him out of the water,’ is to function as God’s rainbow. God knows that he needs a buffer between himself and humanity, and he has chosen Moses precisely because Moses has the courage and wit to play this role.[18]

According to Segal, God chooses Moses to protect God’s people from Himself and to serve as a living reminder of the promise he made to Noah and humanity.

In the case of Ezekiel, God looks like a furious man about to rip off someone’s head, screaming, “Hold me back! Hold me back!”: “I searched for somebody who would stand in the breach against Me on behalf of the land, that I not destroy the land. But I did not find one, and I poured out My wrath upon them” (Ezekiel 22:30-31). In this case, Muffs writes, “In the depths of His heart [God] desperately hopes that the prophet will fight against Him and force Him to cancel His decree. The prophet who is lacking in autonomy and bravery of spirit causes the destruction of the world.”[19] In the case of Jeremiah, God cries out in his fierce anger, “Don’t even try to hold me back!”: “Do not pray on behalf of this people, for even if they fast, I will not listen to their supplication” (Jer 14:11-12). In spite of this, Jeremiah persists, pushing God to own up to his own deceit: “Ah, LORD God! Surely You have deceived this people and Jerusalem” (Jer 4:10). Eventually, when it becomes clear that God will not budge,[20] Jeremiah breaks down and spews out his vitriol and despair: “Why is my pain interminable, and my wound incurable?…Why have You been to me like a dry gulch, an unreliable source of water?” (Jer 15:18). Muffs concludes, “The prophet curses and blasphemes the Lord [and so apparently] God does not oppose prophetic independence that expresses itself in stormy prayer.”[21] The prophet needs to pray prayers “stormy” enough to engage and combat God’s tumultuous wrath.

“Both arguing with God and obeying him,” Levenson concludes, “can be central spiritual acts, although when to do which remains necessarily unclear.”[22] Based on this brief look at the prophetic protests, arguing with God appears appropriate and expected when done on behalf of others. Although the prophets certainly have some ‘skin in the game’ when it comes to the survival and success of Israel, the prophets, for the most part, use their heavy ‘intercessory’ artillery to protect others, and not themselves. Often, they pray vehemently for others at the expense of their own wellbeing and sanity. They are like soldiers going to war so that we might enjoy safety. And in this war, God is the enemy. As Muffs asserts, “The enemy is not the army of the gentiles that is placing a siege around Jerusalem. The Lord himself is the enemy, the warrior who is setting His face against Jerusalem to destroy it.”[23] Sometimes the prophets can keep the enemy at bay. “People can argue with God and win.”[24] Sometimes they cannot. But when it comes to the safety and survival of others, the prophetic option is to argue rather than to obey.

This understanding of prophetic prayer illuminates the acquiescence of Abraham when God tells him to sacrifice his son, Isaac. Abraham does not argue with God about this command because Isaac represents Abraham’s blessing and future. Isaac is an extension of Abraham in a way that his nephew Lot of Sodom is not. If Abraham were to argue on behalf of Isaac he would, therefore, be arguing on his own behalf, and as a result, no longer be engaged in prophetic protest prayer. Instead, he would be engaged in personal protest prayer.

Personal Complaint

As the canon continues into the Ketuvim, the protest prayer tradition expands to allow poets and other non-prophetic individuals to argue with God for their own safety and wellbeing. This expansion may have resulted from a lack of prophets or, more likely, a lack of effective prophets. As the Bible itself shows, the prophets proved mostly unsuccessful in staving off disasters. Sodom and Gomorrah were still destroyed after Abraham’s prophetic intercession. Jerusalem still fell to Babylon after Jeremiah’s prayers.

In his 1994 Preface to Creation and the Persistence of Evil, Levenson highlights “a point usually overlooked in discussions of theodicy in a biblical context.” According to Levenson, “The overwhelming tendency of biblical writers as they confront undeserved evil is not to explain it away but to call upon God to blast it away.”[25] When God fails to respond to these persistent calls, Levenson explains, “one is to continue the argument with [God] in the hope that [God] might yet be cajoled, flattered, shamed, or threatened into acting in deliverance. This,” he asserts, “is the tactic of the lament literature.”[26] This tactic is employed by psalmists in psalms of individual lament as well as by Job. These prayers of protest are not prophetic in the sense that they are not prayed on behalf of others. The “personal complaint” prayers are associated with the Ketuvim more than the Torah and the Neviim, in which “prophetic intercession” dominates.[27] They are impassioned and poetic petitions for deliverance from pain and suffering and often times, impending death.[28] The one praying the personal complaint prayer seeks to avoid suffering and pain, or in the case of Job, at least be given a good reason as to why such suffering is taking place.

Job and many of the psalmists argue with God in their prayers, complaints and laments. They accuse God of not taking care of them, not protecting them, and not keeping His promises. Some of the psalmists, and especially Job, accuse God of not only allowing their suffering but instigating and perpetuating their suffering. Although sometimes the Lament psalmists are rescued from their affliction or at least receive an oracle promising liberation, in many cases, they remain in their dire straits, only able to hope in a God who appears painfully absent. In Psalm 89, God is essentially accused of lying: “You said, ‘I will establish this line forever, his throne, as long as the heavens last’…Yet you have rejected, spurned and become enraged at your anointed” (89:29, 39). In other words, “You promised that there would always be a king on the throne of David. There is no king, so you lied.” God appears to have broken his own ninth commandment.

So the Hebrew Scriptures show an evolution and expansion of the protest prayer tradition from prophetic protest prayer utilized by a select few, primarily for intercession, to personal protest prayer used by individuals and communities. Although the protest prayer tradition proves relatively marginal in relation to other prayer traditions within Scripture such as praise, thanksgiving, and non-protesting petition, the tradition remains a substantial and integral part of the Hebrew Scriptures and thus a significant and viable prayer option for those within the canon and those who uphold it. As we have seen, the protest prayer tradition developed and widened over the centuries that Scripture was recorded. One may wonder, therefore, in what ways the protest prayer tradition continued to develop after the canon of Scripture closed, considering the solid foundation of protest within the canon. History, however, has shown that the tradition became more marginalized after the canon of Hebrew Scripture closed, all but disappearing in Christianity and developing only as a minor prayer tradition within Judaism.

In Protest Against God: The Eclipse of a Biblical Tradition, William Morrow acknowledges the persistence of protest prayer and complaint against God in the Jewish tradition while also recognizing the paucity of protest prayer in the Christian Scriptures and its subsequent Christian spiritualities. Though remaining mostly marginal, the protest prayer tradition within post-biblical Judaism still endures and develops, as authors like Anson Laytner and David Roskies show in their respective works, Arguing with God: A Jewish Tradition and The Literature of Destruction: Jewish Responses to Catastrophe. Offering a brief survey of the prayer tradition himself, Morrow highlights protest against God in Rabbinic, Hasidic, and post-Shoah sources.[29] Concerned with the marginalization of protest prayer in Judaism, Morrow suggests reasons for its suppression in Jewish liturgy. The dominance of Deuteronomic theology overwhelmed protest prayer, according to Morrow, while the revolutionary sentiments associated with protest prayer gave Jewish authorities ample reason to keep the tradition suppressed. Morrow also stresses how the concept of divine transcendence (emerging in the Axial Age) and redemptive suffering (emerging in Second Temple Judaism) contributed to the decline of protest prayer in Judaism. However, the tradition persisted nonetheless, in spite of its marginality. While Morrow explores reasons for the tradition’s suppression, he fails to offer any reasons for the tradition’s persistence in Judaism, especially in contrast to the near absence of the tradition in Christianity.[30] What accounts for the persistence and development of the protest prayer tradition in Judaism and its disappearance in Christianity?

WHY PROTEST PRAYER DISAPPEARS IN CHRISTIANITY

Although the Hebrew Scriptures may reveal a development from an immanent God to a more transcendent divinity as Morrow suggests, Jewish historian Daniel Boyarin asserts the popular desire, in Second Temple Judaism, for a divinity that is simultaneously immanent and transcendent. The desire for the immanent-and-transcendent God gave birth to the theology of the Logos. “The Logos,” Boyarin explains, “came into general popularity because of the wide-spread desire to conceive of God as transcendent and yet immanent at the same time.”[31] The Logos, which also bore the name “Memra” or “Metatron,” served as a divine mediator between heaven and earth. We see this in the book of Proverbs, where the Wisdom of God (Sophia), personified as a woman, exists before creation and is active during creation and continually calls out in the streets, eager to share her many blessings with humanity. Sophia can be understood as a divine entity who is part of the one God. We also see this divine mediator in the works of Philo, a Jewish mystic of the early first century, who explained that the wisdom of God is the Logos of God,[32] declaring, “This Logos of God is continually a suppliant to the immortal God on behalf of the mortal race, which is exposed to affliction and misery; and is also the ambassador, sent by the Ruler of all, to the subject race.”[33]

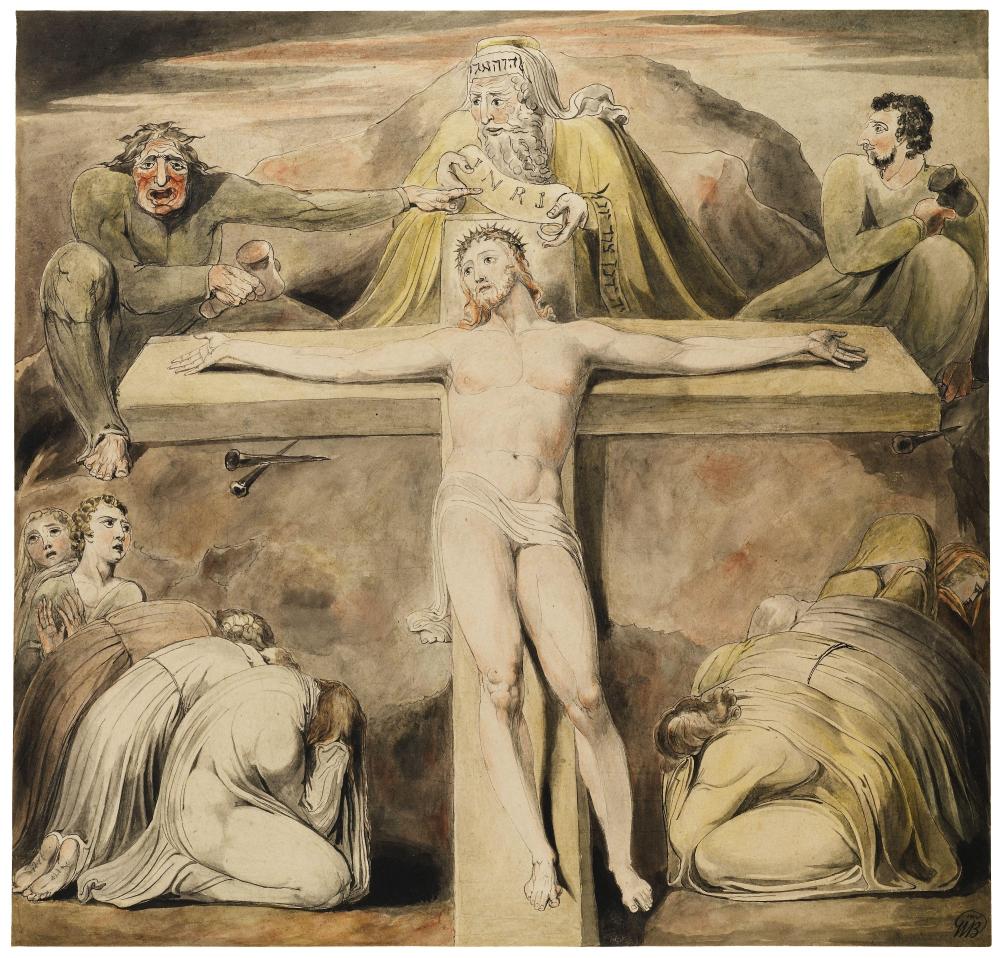

When the author of the fourth Gospel wrote his prologue, he synthesized the Wisdom of God in Proverbs with the Logos of God in Philo to describe the Word of God in the Gospel, who became flesh and dwelt among us. With this prologue, the theology of the Logos is transferred onto Jesus of Nazareth, thus making Jesus the divine mediator who is also one with the Godhead. As divine mediator, Jesus takes on the role of prophet par excellence, and in this way, Jesus embodies the prophetic protest prayer tradition in which the prophet stands in the breach between God’s impending punishment and God’s people, protesting and reminding God of his patient forbearance.

Jesus and Prophetic Intercession

Although Morrow argues that the Hebrew prophetic tradition promoted the concept of divine transcendence to the detriment of protest prayer, Yochanan Muffs stresses the crucial role that protest prayer played among the prophets as shown above. The Gospels clearly portray Jesus as a prophet in the same tradition of Abraham and Moses and the other Hebrew prophets.[34] Based on the above description of the prophet as one who stands in the breach between God’s wrath and God’s people, we must ask how Jesus served as such a prophet. According to Christianity and Christian theories of atonement, one of the cosmic consequences of Christ’s death on the Cross is Christ’s perpetual mediation and intercession between God’s anger and humanity’s sin. The Gospel of Luke underscores Christ’s prophetic and intercessory role on the Cross when he writes about Jesus interceding while being crucified: “Jesus said, ‘Father, forgive them for they do not know what they are doing.” (Luke 23:34). Moreover, Jesus substitutes himself for God’s people and receives the punishment that the wrathful God seeks to inflict upon them. In this way, Jesus’ death can be understood as a prophetic protest against God’s wrath and God’s desire to punish His people. If this were the end of the story, then Jesus might be seen as a great Jewish prophet and martyr who protested against God’s wrath and interceded on behalf of God’s people to the point of death. However, since the Logos was transferred onto Jesus, he becomes much more. He becomes divine and his actions therefore become infinitely significant. His mediation and intercession transcend history and rise to the status of “eternal.” As a result, Jesus Christ stands in as humanity’s perpetual intercessor and protestor against God’s wrath. Not only would it be impossible for humans to play such a role, but humans no longer need to play such a role since that role has already been filled, for eternity, by the best possible candidate. Therefore, with Christ as eternal intercessor and prophet, the tradition of prophetic protest prayer becomes obsolete in Christianity. But what about personal protest prayer?

Jesus and Personal Complaint

Although still a prophet, Jesus practices the prayer of personal complaint as well. In the Garden of Gethsemane, Jesus takes on the role of the lament psalmist, praying for personal liberation from suffering and impending death. In Matthew and Mark, Jesus echoes the passionate prayers of the Psalms when he prays, “My soul is overwhelmed with sorrow to the point of death.”[35] Several psalms all share similar language in describing “overwhelming” emotions.[36] Also in the spirit of personal complaint, Jesus boldly yet humbly petitions the Lord for his cup of suffering to be removed, “Abba, Father, for you all things are possible; remove this cup from me.”[37] In Matthew and Mark, Jesus repeats this prayer three times! Just in case God didn’t hear him the first two times. Although Luke only records Jesus praying once, a later redactor tries to makes up for the triple prayer by describing Jesus sweat drops of blood to convey the intensity of his agony.

Considering the fact that the Gospels portray Jesus praying a personal protest prayer at least seven times, one would think that Christians would feel empowered to do the same, to bring their suffering before God and boldly ask Him to do something about it. However, Jesus’ personal protest prayer becomes less of a protest and more of a sad submission as it changes from Mark to Matthew to Luke. Matthew turns Jesus’ imperative “remove this cup” into a jussive “let this cup pass from me.” Mark’s Jesus boldly reminds God of his power to save (“for you all things are possible”) in order to make God act while Matthew’s Jesus submissively begs, “If it is possible.” Luke keeps the imperative, but adds “If you are willing” and subtracts the other two repetitions of the prayer.

In Paul’s second letter to the Corinthians, he describes how he himself prayed three times for God to remove his suffering, most likely in imitation of Jesus’ prayer.[38] However, like Jesus, Paul’s request is not granted. As a result, the suffering, which both Jesus and Paul prayed to avoid, later becomes understood as not only necessary, but profoundly beneficial and redemptive, thus fueling the theology of redemptive suffering which reaches new heights of popularity in Christianity. In the Gospel of John, written decades after the Synoptic Gospels, Jesus does not pray for his suffering to be removed at all but almost seems to look forward to his suffering, which he describes as his glorification: “Father, the hour has come. Glorify your Son, that your Son may glorify you” (John 17:1). So the submission to the suffering eventually eclipses the protest to the suffering entirely. As a result, personal protest prayer also becomes obsolete because the suffering one seeks to avoid will likely prove beneficial and redemptive. Futhermore,, if God refused to grant the bold and persistent petitions of his beloved Son Jesus Christ and St. Paul, then why in the world would he grant the bold and persistent petitions of their followers?

WHY (AND HOW) PROTEST PRAYER PERSISTS IN JUDAISM

While the Christian transference of the Logos onto Jesus resulted in the disappearance of protest prayer in Christianity, Jewish transference of the Logos tradition onto the Torah equipped the Jewish people with an effective tool and weapon in their arguments with God, thus fueling their protest prayer.[39] In demarcating the partition of Judaeo-Christianity into what later became orthodox Christianity and rabbinic Judaism, Boyarin argues that the final “definitive move for the Rabbis” was the transfer of “all Logos and Sophia talk to the Torah alone.”[40] By doing this, the Rabbis accomplished two things: they gave themselves the power to act as the sole interpreters and leaders of the tradition while also maintaining a strict monotheism.[41] However, I would add another achievement to Boyarin’s list of accomplishments resulting from the transfer of the Logos to the Torah. By elevating the Torah to the status of Logos and divine mediator, the Rabbis equipped themselves with a tool, nay a weapon, to argue more assertively and aggressively with their God. We can see the elevated status of Torah in Genesis Rabbah 1:1, which claims that God consulted the Torah in creating the Universe.[42] Like the Logos and Sophia, the Torah existed in the beginning, during creation. However, according to this midrash, the Torah precedes creation. In fact, the Torah serves as God’s blueprint for creation. God consults the Torah before creating the heavens and the earth and, according to the Talmud, God continues to study Torah three hours a day.[43] In some ways, it appears that the Torah might have greater authority than God himself since God appears to be a student to its teachings. Furthermore, God appears open to having his interpretation of Torah overruled by human interpretation, as in the story of the Oven of Akhnai.

Rabbinic Boldness Against Heaven

In the Talmudic tractate Bava Metzi’a, a story is told about an argument between Rabbi Eliezer and a group of other rabbis regarding the oven of Akhnai. The rabbis insist that the oven cannot be purified while Rabbi Eliezer argues that it indeed can be made pure. In order to prove his argument correct, Rabbi Eliezer performs a series of miracles, causing a carob-tree to move, a stream to flow backwards and walls to bend. Finally, a voice from heaven affirms that Rabbi Eliezer is correct. Yet, even after the heavenly voice, the rabbis use the Torah to prove that they are in fact correct and Rabbi Eliezer is wrong. As a result, God laughs with delight at the sages and declares, “My children have defeated me, my children have defeated me.”[44] Although the rabbis are not engaged in protest prayer or complaint against God, they are still in contest with God, with the divine voice. They are not holding God responsible for any suffering or accusing God of any malfeasance. They are simply arguing over halakha and disagreeing with God in this particular case. What is important to highlight in this aggadah is the fact that the rabbis have no fear or hesitation about arguing and disagreeing with God. “Boldness,” according to the Talmud, “is effective—even against Heaven.”[45] Also, God lets them win or perhaps recognizes the superiority of their argument. And God delights in their victory. God, as the loser, laughs. Though the tradition of protest prayer might take a back seat in Talmudic literature, boldness against Heaven remains strong as ever, and is even welcomed by God.

If the Torah enjoys divine status due to the transfer of the Logos and the rabbis have just as much authority in interpreting the Torah as God (if not more), then the rabbis are equipped with a tremendous resource to argue with God. With this understanding, perhaps we should be surprised that this tool for arguing with God was not utilized more often. It is important to note that it was the rabbis who had this power to interpret Torah against God. In the particular passage of the Oven of Akhnai, the rabbis may have simply been asserting authority over miracle-workers (represented by Rabbi Eliezer) and voices from Heaven. Either way, the Talmud laid the foundation for Jewish people to use the deified Torah to argue against their God.

Another example of the Torah being used in an argument with God is found in Lamentations Rabbah, in which Abraham asks God, “Who testifies against Israel that they transgressed the law [and should therefore be punished so severely?].” God responds by telling the Torah to come and testify against Israel. However, God’s plan backfires when Israel’s advocate, Abraham, reminds the Torah of how all the nations rejected her except for Israel. Remembering Israel’s acceptance, the Torah “stood aside and gave no testimony against them.”[46] God then calls on the twenty-two letters of the Hebrew alphabet in which the Torah is written to testify against Israel. Again, His plan backfires when Abraham reminds aleph of how Israel accepted the Torah when other nations rejected her, beth of how zealously Israel embraced the Torah at Sinai, and gimel of how the Israelites observe the commandment of the fringes.[47] As a result of Abraham’s reminders of Israel’s faithfulness, the first three Hebrew letters as well as all the subsequent Hebrew letters stand aside and refuse to testify against Israel. The three patriarchs and Moses then proceed to cite their faithfulness as attested to in the Torah and finally conclude with a complaint. By refusing to testify against Israel when called upon God to do so, the Torah indirectly accuses God of unjustly punishing Israel. If Israel’s disobedience to the Torah is the only reason for God’s punishment of Israel and the Torah itself refuses to corroborate with this allegation, then the fault falls back on God, who can provide no reason for punishing Israel. Thus, Abraham and the others end up using the Torah to condemn God.

The Torah continues to be used to condemn God in more subtle ways throughout the Jewish protest prayer tradition. The Torah, which upholds justice and responsibility, confers upon the Jewish people a keen sense of ethical values, forcing them to confront the dissonance inherent in having a deity who fails to meet such standards. This dissonance compels the Jewish people to ask the age-old question of suffering in a way that is not afraid of sounding accusatory or condemning. According to a Jewish midrash, it was asking the question of suffering that gave birth to Judaism. God’s call to Abraham is compared to a man nonplussed by a house in flames, who asks, “Is it possible to say that such a great house has no one in charge?”[48] In the same way, Abraham asks, “Is it possible for the world to endure without someone in charge?”[49] His question entertains the possibility that there is either no ruler or that there is an irresponsible and incompetent ruler. Like the house in flames, the beautiful world appears to be wracked by violence and suffering. Abraham’s question, which calls the ruler of the world to task, receives an answer from God: “I am the one in charge of the house, the lord of all the world.” The divine response awakens enough faith and trust within Abraham for him to devote his entire life and family to God, giving birth to a people that will continue to ask bold and accusatory questions of God, propelled by the ethical power of the Torah.

Kabbalistic Accusation

As the rabbis continued to bring their boldness against Heaven in the form of accusatory questions of suffering, the Jewish mystical tradition was emerging and developing its own theological attempt to hold together both the ethical standards of the Torah and the God who appears to fall short of such standards. Although the Jewish mystic tradition claims to have origins in the esoteric teachings of Palestinian teacher Shimon Bar Yochai of the second century CE, the tradition, which came to be known as Kabbalah, did not receive popular attention until the publication of the Zohar in the 13th century. However, the popularity of Kabbalah still did not reach its peak until the 16th century, when Isaac Luria formulated a theology that managed to hold God responsible for the world’s suffering in a way that leads not to despair but rather to repair. In the wake of the expulsion of the Jews from Spain in 1492 and subsequent pogroms against Jews throughout Europe, Isaac Luria began to describe creation itself as flawed from the start. In order to create something that exists apart from God, according to Lurianic Kabbalah, God had to withdraw Himself in order to create an empty space, devoid of God. This withdrawn space became the void, which God then infused with some of His divine light. However, this void could not contain the power of the divine light and so it shattered into tiny pieces in a process known as shevirah. The duty of humanity, therefore, is to re-gather and restore these broken shards in the communal work of tikkun, or reparation. “God,” according to Estelle Frankel, “created a flawed universe in order to give every creature a role in its restoration.”[50] According to Lurianic Kabbalah, even the smallest act of obedience to the Torah works to restore the broken shards of creation. Although this system is effective in causing humanity to take responsibility for the suffering in the world by obeying the Torah, the system still accuses God of failing in His creation. Though the teachers and students of Kabbalah do not engage in protest prayer, they engage in a form of protest against God’s creation by obeying the Torah. Luria’s theology of creation can be understood as a form of protest theology, which accuses God of failing in his creation by making a flawed world, full of suffering. The Jewish people employ the deified Torah as a tool in order to clean up God’s mess. They protest not with their prayers, but with their deeds.

Hasidic Judgment

Accusation against God reunites with protest prayer, particularly in the prayers of 18th century Hasidic leader Rabbi Levi Yitzhak of Berditchev. Known as the “champion prosecuting attorney of the Hasidim,” Levi Yitzhak brings the suffering of his people before God in prayer and then boldly holds God responsible for all of it in order to get God’s attention and bring salvation to his people.[51] He prayed, “O Lord, if you want the throne of Your glory to be established…, then deal mercifully with Your children and issue decrees for their salvation. But if you deal with us harshly then the tzaddikim of the generation will not permit You to sit upon Your throne. You may decree, but they will annul.”[52] In other words, “God, if you want to be treated and worshiped as our God then start acting like our God and show us some mercy!” In his bold prayers of protest, Rabbi Levi Yitzhak acts as though he has the power and authority to kick God off His throne for not taking care of His people. Levi Yitzhak offers no theology to reconcile the dissonance between the deified Torah and the God who fails to follow it. Instead he brings the dissonance to God in prayer and prays prayers of intercession for Israel, not too unlike the intercessions of the biblical prophets.

Boldly, Levi Yitzhak interprets the verse “They stand this day for Your judgments, for all things are Your servants” (Psalm 119:91) to mean “they stand this day—if one may utter it—to judge You! ‘For all things are your servants,’ that is, they judge You for everything we bear—wicked and cruel decrees, pogroms and persecutions, poverty and sorrow—all these things are come upon us only because ‘we are Your servants.’”[53] In this interpretation, Levi Yitzhak puts God on trial and blames God for all the suffering and sorrow of the Jewish people. Levi Yitzhak is the plaintiff; God the defendant; and the ethics of the Torah preside as Judge.

In Arguing with God: A Jewish Tradition, Anson Laytner traces the law-court pattern of prayer throughout the Jewish protest prayer tradition. “The appeal,” Laytner writes, “is both against God yet also to God, making Him, paradoxically, both judge and defendant.”[54] Reminiscent of the paradox presented in Buber’s reading of Job, the appeal to God against God comes to light when we understand the deified Torah as the divine judge and mediator between humanity and God. Using the ethics of the Torah as Judge against God is a prayer practice that continues with new momentum and anger in the modern era, in light of new catastrophes such as the Shoah.

Post-Shoah Anger

After the horror of the Holocaust, authors and theologians tapped into the protest prayer tradition with an urgent intensity. Throughout most of Jewish tradition, we only have records of rabbis and other spiritual leaders utilizing the Torah as a weapon in their protest prayer. However, in post-Shoah literature the use of the Torah as a weapon against God becomes more popular and accessible. In the case of Zvi Kolitz’s Yossel Rakover Speaks to God, the speaker confesses, “I love [God], but I love His Torah more, and even if I were disappointed in Him, I would still observe His Torah.”[55] Although Yossel loves God, he loves the Torah even more and uses the ethics of the Torah to judge and question and protest against God. After this confession, he writes, “Therefore, my God, allow me…to argue things out with You for the last time in my life…You say that we have sinned? Of course we have. And therefore that we are being punished? I can understand that too. But I would like You to tell me whether any sin in the world deserves the kind of punishment we have received.” Yossel knows from the Torah that sin deserves punishment, but he also knows from the Torah that the punishment should fit the crime. He cannot fathom what crime deserves the punishment that he has undergone. Certainly there is no such crime. So Yossel confronts and judges God with the ethics of the Torah. And, under judgment of the Torah, God appears wholly guilty of excessive punishment.

In his reflection on Yossel Rakover Speaks to God, Emmanuel Levinas writes, “Matured by a faith derived from the Torah, [Yossel] blames God for His unbounded majesty and His excessive demands. He will love God in spite of His every attempt to discourage his love.”[56] The fictional character Yossel Rakover represents the Jewish people who are “matured” by the ethical standards of the Torah and then hold God up to those same standards. When God fails to meet these standards, the Jews still love Him, because the Torah has also taught them to forgive.[57] “The text,” Levinas continues, “shows how ethics and the order of first principles combine to establish a personal relationship worthy of the name. To love the Torah more than God—this means precisely to find a personal God against whom it is possible to revolt.”[58] So loving and obeying the Torah becomes a way of judging and revolting against God.

This same approach of judging God with the ethics of the Torah is also utilized by Elie Wiesel, particularly in his Trial of God, in which God is actually put on trial for the crimes he committed against God’s people and deemed guilty. The protest prayer tradition reaches its vitriolic peak in the work of David R. Blumenthal, who in Facing the Abusing God: A Theology of Protest writes, “We will point the finger, we will identify the Abuser, we will tell this ugly truth. We will not keep silent, neither out of fear nor out of love. We will not be drawn into the conspiracy of silence, or into the cabal of rationalization. We will cling tenaciously to our rage, and we will speak. And, in our speaking, we will accuse, we will place the blame where it belongs. We will say, ‘The fault was not ours. You are the Abuser. The fault was yours. You repent. You return to us.’”[59]

CONCLUSION:

Meanwhile, Back at Job’s Dung Heap…

Although the protest prayer tradition remained marginalized in Judaism, we can see how the transfer of the Logos to the Torah gave the tradition fuel to persist and develop into a rich resource for dealing with horrific suffering, in spite of its suppression. Unlike Christianity, which transferred the Logos to Christ thereby making protest prayer obsolete for Christians, Judaism’s transfer of the Logos to the Torah laid the foundation for a tradition of protest prayer that helped frame Jewish responses to catastrophes, such as the Shoah.

Author Harold Kushner reads the idea of using Torah to grab God’s attention back into the Book of Job. In The Book of Job: When Bad Things Happened to a Good Person, Kushner argues that God appears to Job only after Job invokes the Torah. “Job,” Kushner explains, “is not an Israelite, of course, and not bound by the Torah, but the author and his readers might well assume that God’s standards of justice extend to all societies.”[60] Kushner then draws attention to Exodus 22: 10-11, which reads,

When someone delivers to another a donkey, ox, sheep, or any other animal for safekeeping, and it dies or is injured or is carried off, without anyone seeing it, an oath before the LORD shall decide between the two of them that the one [who was in charge of the property while the owner was away] has not laid hands on the property of the other; the owner shall accept the oath, and no restitution shall be made.

According to Kushner, in Job’s final discourse, he invokes this law and swears an oath of his innocence: “As long as God lives…I hold fast my righteousness” (Job 27:2, 6). Job, in Kushner’s words, is saying,

I have begged and pleaded. I have proclaimed my innocence. I have asked Why? But I received no answer from God. Now I will use this one last, desperate tactic in my quarrel with God. No more pleading, no more begging. I invoke God’s own law against Him. I hereby swear in the name of that same God who has denied me justice but in whom I still believe that I am innocent of all possible charges. I swear by the Name of that God that I have done nothing wrong. God, according to Your own laws, You are required to appear in court, to present evidence against me or, by failing to do that, recognize me as innocent and drop all charges.[61]

After Job swears by his oath of innocence, God finally appears. Kushner’s creative reading of Job’s “final tactic” reveals more about Kushner’s own spirituality than that of the book of Job, showing once again how the protest prayer tradition in Judaism has evolved since Job to the extent that the Torah has become an employable and effectual tool for protest and argument with God.

In attempting to find one reason why protest prayer persists in Judaism beyond the Hebrew Scriptures while it disappears in Christianity, we have seen how the transfer of the Logos to the Torah equipped the Jewish people with an effective “judge” to take God to court. The deified Torah continued to be used throughout the Jewish tradition of protest prayer. The rabbis used the Torah to strengthen their boldness against heaven by making it backfire against God in Lamentations Rabbah. The Kabbalists used it to clean up God’s mess, thus accusing God of His failure every time they fulfill a commandment and repair a broken shard of the flawed creation. Hasidic leaders like Levi Yitzhak used the Torah to judge God and put Him on trial as the divine defendant answering to the ethical standards of the deified Torah. Post-Shoah authors amplified the admonishments against God with their anger and vitriol under the shadow of the Shoah. The Torah empowered the Jewish people to argue with God, to vent, and to unleash their anger in the face of traumas and catastrophe.

AFTERWORD:

So What?

According to the renowned psychiatrist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, one of the major emotional responses to catastrophe and loss is anger. Mostly in order to caution nurses and family members, she explains, “This anger is displaced in all directions and projected onto the environment at times almost at random.”[62] Hospital patients in the anger stage often blame nurses and caretakers irrationally for either coming in to the patient’s room too often or not enough. Anger, in order to be expressed, often seeks a scapegoat upon which to unleash itself. French anthropologist René Girard describes a similar phenomenon occurring at a sociological and anthropological level. Instead of anger, however, Girard discusses human violence and its need to be unleashed on a scapegoat. “Society,” he posits, “is seeking to deflect upon a relatively indifferent victim, a ‘sacrificeable’ victim, the violence that would otherwise be vented on its own members.”[63] Although Girard and Kübler-Ross certainly differ in their agendas and conclusions, they both attest to the human propensity to blame, and vent and lash out in response to crisis and catastrophe and the inevitable anger that ensues. The protest prayer tradition creates space for humanity to vent their anger towards the divine. The tradition allows humanity to direct anger and the propensity to blame towards God. With this protest prayer tradition at their disposal, the Jewish people have retained their rich spiritual heritage in the face of horrifying opposition. Recently, within the last few decades, a Christian movement has emerged led by scholars such as Walter Brueggemann to reclaim the protest prayer tradition as an effective resource for dealing with suffering and catastrophe. In attempting to reclaim protest prayer, it would behoove Christians to sit at the feet of those who have been utilizing and developing the prayer tradition beyond the canon of Scripture for the last two millennia.

[1] Job 9:33 (all biblical citations are from the NRSV translation)

[2] “Job struggles [to] “see” God (19:26) as His “witness” (16:19) against God Himself, [to] see Him as the avenger of his blood (19:25), which must not be covered by the earth until it is avenged (16:18) by God on God. The absurd duality of a truth known to man and a reality sent by God must be swallowed up somewhere, sometime, in a unity of God’s presence.” Martin Buber, On the Bible: Eighteen Studies (New York: Schocken Books, 1982), 193.

[3] One might argue that the Book of Job demonstrates the moral and spiritual lacuna within non-Jewish prayer: that is, the lack of Torah. Perhaps non-Jews like Job have a much more difficult time getting God’s attention in prayer because they do not have the same access to the Torah, which serves as the divine expression of justice, the heavenly arbiter. This argument would be emboldened by evidence of Jews in Hebrew Scripture using the Torah to invoke God’s justice and liberation. Although psalmists make references to the Exodus, to Sinai and to Torah-prescribed sacrifices, they do not utilize the Torah enough in their prayers to indicate that God’s “ears” are especially “perked” at the sound of his Law.

[4] Buber, 192.

[5] Buber, 193.

[6] Yochanan Muffs, Law, Language and Religion in Ancient Israel (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 1992), 45.

[7] William Morrow, Protest Against God: The Eclipse of a Biblical Tradition (Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix Press, 2006), 1.

[8] Jon D. Levenson, Creation and the Persistence of Evil: The Jewish Drama of Divine Omnipotence (Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press, 1994), 149.

[9] Muffs, 9.

[10] Richard Elliott Friedman, Commentary on the Torah (New York: HarperCollins, 2001), 65.

[11] J. H. Hertz explains that “I will go down” is “an anthropomorphic expression…to convey the idea that before God decided to punish the dwellers of the cities, ‘He descended,’ as it were, to obtain ocular proof of, or extenuating circumstances for, their crimes.” J. H. Hertz, The Pentateuch and Haftorahs (London: Soncino Press, 1960), 65.

[12] Levenson, 152.

[13] According to Chullin 89A, God said, “I deeply love you [Israel], for even when I give you abundant greatness, you make yourselves small before Me. I gave greatness to Abraham, and he said ‘I who am but dust and ashes.’”

[14] Levenson, 151.

[15] Muffs, 11.

[16] The Jewish Study Bible, edited by Adele Berlin and Marc Zvi Brettler (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), 40.

[17] Ex. 32:12, 13.

[18] Jerome M. Segal, Joseph’s Bones: Understanding the Struggle Between God and Mankind in the Bible (New York: Riverhead Books, 2007), 124.

[19] Muffs, 31-32.

[20] “Even if Moses and Samuel were to intercede before me, I would not be moved.” (Jeremiah 16:10).

[21] Muffs, 30.

[22] Levenson, 153.

[23] Muffs, 31.

[24] Levenson, 149.

[25] Levenson, xvii.

[26] Levenson, xviii.

[27] Since the books of the Ketuvim are generally considered to be written later than the books of the Torah and Neviim, one might argue that there is a historical development from prophetic prayers on behalf of others to personal protest prayers. However, many of the Psalms, which contain a bulk of the personal protest prayers, may have been written as early as the 10th century BCE, earlier than many of the books in the Torah and Neviim. Nevertheless, one may recognize a canonical development from prophetic to personal prayer since the Torah and Neviim precede the Ketuvim in the Tanak.

[28] It is important to note that many of these individual prayers have been used to pray for the deliverance of the nation wherein the individual “I” in the prayer represents the plural “we” of the people. In this way, such personal prayers become somewhat prophetic. However, even when the individual stands in for the nation, the person (or persons) praying still has a personal stake in the prayer more than the prophet, who is often willing to suffer on behalf of the people.

[29] Morrow, 208.

[30] Morrow offers the following caveat: “An exception to this generalization is the African-American spiritual tradition” and notes David E. Goatley’s Were You There? Godforsakenness in Slave Religion (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1996) 53, 71-72.

[31] Daniel Boyarin, Border Lines: The Partition of Judaeo-Christianity (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004), 112.

[32] Philo, Allegorical Interpretation 1:65, http://www.earlychristianwritings.com/yonge/book2.html (accessed December 21, 2012).

[33] Who is the Heir of Divine Things, 205-206, http://www.earlyjewishwritings.com/text/philo/book17.html (accessed December 21, 2012).

[34] Matthew 13:57; Mark 6:4; Luke 24:19; John 1:45, 6:14.

[35] Matthew 26:38; Mark 14:34.

[36] Psalms 61:2; 42:5; 142:3 and 119:20

[37] Mark 14:36; Matthew 26:39; Luke 22:42.

[38] Although the Epistles were written before the Gospels, it is likely that the story of Jesus’ three prayers in the garden was well known among the churches by the time Paul was writing.

[39] Reasons for the persistence of protest prayer within Judaism are manifold, including historical, sociological, ethnological, and literary factors. Due to the limitation of the paper, I am focusing on a historical and theological reason: the transfer of the Logos onto the Torah.

[40] Boyarin, 129.

[41] Ibid.

[42] “The Torah speaks, ‘I was the work-plan of the Holy One, blessed be he.” Jacob Neusner, A Theological Commentary to the Midrash: Genesis Raba (Lanham MD: University Press of America, 2001), 2.

[43] Avodah Zarah 3b

[44] Bava Metzi’a 59b

[45] Sanhedrin 105a

[46] Eichah Rabbah, in The Literature of Destruction: Jewish Responses to Catastrophe, edited by David G. Roskies (New York: Jewish Publication Society, 1989), 53.

[47] Abraham reminds aleph that God’s revelation on Mt Sinai opens with aleph when God said, “I am the Lord your God.” He reminds beth that the Pentateuch begins with beth in bereshith. And he reminds gimel that gimel is the first word in the commandment to wear fringes: גְּדִלִים

[48] Genesis Rabbah 39:1

[49] Some interpret the “castle in flames” דולקת אחת בירה to refer to a “well-lit mansion” or a castle with a warm hearth burning inside, keeping family and friends warm. Following this interpretation, Abraham stands in awe of a beautiful world, which provides and cares for a beloved humanity and, therefore, wonders who is responsible for the beauty. In other words, “Who should be thanked?” I do not find this interpretation convincing mostly because of the way the question is asked, entertaining the possibility that there is no ruler/owner based on the evidence: “Is it possible that the palace has no owner?” Is it possible that the world lacks a ruler?” Furthermore, this alternate interpretation does not alter the fact that Judaism is still born out of a question.

[50] Estelle Frankel, Sacred Therapy: Jewish Spiritual Teachings on Emotional Healing and Inner Wholeness (Boston MA: Shambhala Publications, 2003),37.

[51] Anson Laytner, Arguing with God: A Jewish Tradition (New Jersey: Jason Aronson, 1990),

180.

[52] Samuel H. Dresner, Levi Yitzhak of Berditchev: Portrait of a Hasidic Master (New York: Hartmore House, 1974), 81.

[53] Ibid.

[54] Laytner, xviii.

[55] Kolitz, 22.

[56] Emmanuel Levinas, “To Love the Torah More than God” in Yossel Rakover Speaks to God: Holocaust Challenges to Religious Faith (Hoboken NJ: KTAV Publishing House, 1995), 31.

[57] In the final chapter of Facing the Abusing God: A Theology of Protest, David Blumenthal writes, “It is not my place to suggest modifications to Christian liturgy, but in the interest of dialogue and without intending any offense whatsoever and in the spirit of theology of protest, I offer the following inter-pretation of the Lord’s Prayer: ‘Our Father….Forgive us our sins, as we forgive those who sin against us. Ask forgiveness of us, as we ask forgiveness of those who wrong us. Lead us not into temptation…” David Blumenthal, Facing the Abusing God: A Theology of Protest (Louisville KY: John Knox Press, 1993), 297.

[58] Levinas, 32

[59] David Blumenthal, Facing the Abusing God: A Theology of Protest (Louisville KY: John Knox Press, 1993), 267.

[60] Harold Kushner, The Book of Job: When Bad Things Happened to a Good Person (New York: Schocken Books, 2012), 125.

[61] Kushner, 126.

[62] Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, On Death and Dying: What the dying have to teach doctors, nurses, clergy and their own families (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1997),64.

[63] René Girard, Violence and the Sacred, translated by Patrick Gregory(Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1977), 4.